Henry Schvey delves into the ongoing cultural relevancy of the Frankenstein mythos, finding new and richer meanings in the two centuries since its publication. At its heart, Schvey says, the Frankenstein story reflects the unresolved anxiety between creator and creation.

A popular fruit-flavored breakfast cereal marketed to children (Frankenberry); John Milton’s Paradise Lost; Donald Trump’s unlikely adoption by the Republican Party; scary Halloween masks; concerns regarding global warming; horror films; fears about human cloning; contemporary notions of Otherness; unbridled scientific hubris; Black Lives Matter; atheism; Adam and Eve; feminist theory; Herman Munster; camp musicals like Young Frankenstein and The Rocky Horror Picture Show; cartoons, comics, graphic novels — these are some, but far from all, of the associations we may have with the central myth of the past 200 years: Frankenstein.

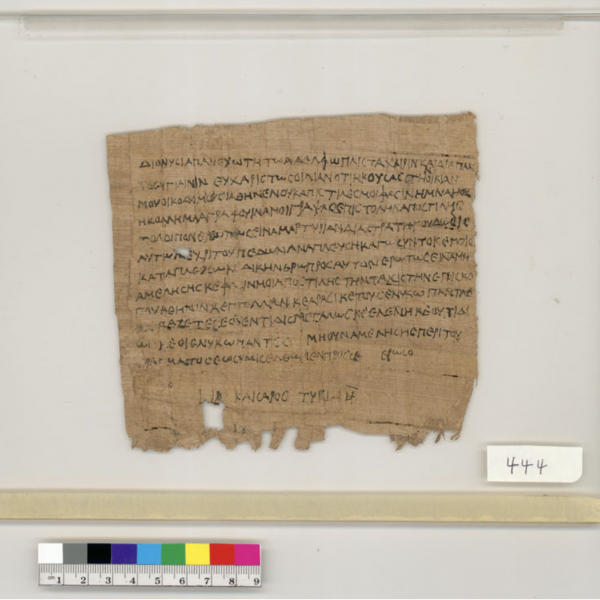

Brought to life by a 19-year-old girl, the myth of Frankenstein has grown in popularity and significance ever since its remarkable birth at a ghost story contest held at the Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva in 1816. Young Mary Shelley was unable to sleep after listening to a group of men (including the poets Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, the latter with whom she had recently eloped) discuss means of reanimating life from dead tissue. She had attended their conversation about electrical impulses and galvanic piles as a “devout but nearly silent listener,” and, as she lie in bed, began to conceive her terrifying tale in a drowsy state of half-dream, half-wakefulness: “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.”

However, despite her scientist’s prowess in creating life, Shelley’s novel also recognizes the very human weakness at Dr. Frankenstein’s core.

He has managed to create new life from inanimate material and initially contemplates the perfection of his achievement: “His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful!” But no sooner has he given birth to his living creation, he flees in abject terror, unable to “endure the aspect of the being I had created.”Godlike, Dr. Frankenstein has succeeded in creating life, but having done so, retreats fecklessly back into his humanity, abandoning his creation: “He might have spoken, but I did not hear; one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped and rushed down stairs.” As the novel’s subtitle, “The Modern Prometheus,” suggests, the character of Victor Frankenstein may be viewed either as heroic (Prometheus valiantly stole fire from the gods and bestowed it on man) or as an overreacher who has gone beyond his human limits and must be punished for it, just as Prometheus was punished for his transgression by Zeus. Like that other archetypal myth of human aspiration, Faust, Frankenstein may be read as a moral exemplum of courage in man’s opposition to an implacable supernatural and monstrous foe or pitiful cowardice as a weak-kneed creator abandons his creation, his child.

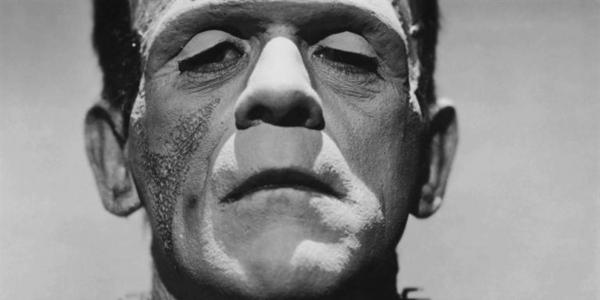

If one aspect of the myth’s compelling legacy is the ambiguity of the brilliant and irresponsible genius who summons life, yet fecklessly retreats from its consequences, another dilemma is even more suggestive — the problem of coming to terms with the monster himself. Perhaps Shelley’s greatest literary coup was her decision to leave the monster nameless; by so doing, she created an enigmatic figure who combines both innocence and monstrosity. At once childlike and demonic, the Creature is both Adam and Satan. The novel’s epigraph from Milton’s Paradise Lost reminds us of the creature’s essential innocence:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould Me man? Did I solicit thee:

From darkness to promote me?—

Indeed, 21st-century audiences are far more likely to see the story from the Creature’s viewpoint; he is an innocent naïf who has been irresponsibly abandoned by his father/creator and rejected by society. Despite his heroic efforts to educate himself and act with generosity toward others, he is mercilessly mocked and mistreated because of his physical appearance. Only after his complete rejection, both by his father/maker and by society, does the Creature turn to violence and retribution. We can readily understand how the Frankenstein myth plays into contemporary notions of Otherness and racial victimization. The motif of countless villagers all seeking “justice,” screaming and bearing flaming torches in pursuit of the fleeing monster, does not exist in Mary Shelley’s novel, but its iconic status (from the legion of film adaptations) is still potent today. Indeed, it was summoned just weeks ago, as a group of white supremacists in Charlottesville wielded burning torches in support of irrational and violent hatred.

Perhaps the most interesting comment on the remarkable pervasiveness of the myth today is how familiar it has become — familiar even to people who have never heard of Mary Shelley or read her novel. Indeed, the common confusion in calling the Creature “Frankenstein,” the name of his maker, is perhaps the greatest testament to the story’s total immersion in our popular imagination. In our own fantasies, the scientist and his lonely creation are two indistinguishable halves of a single human whole. And that is just the way its author would have wanted us to see her profoundly ambiguous, always evocative creation.