Heidi Aronson Kolk is associate professor in the Sam Fox School, where she teaches in the Illustration and Visual Culture MFA program. Her scholarship exploring the visual and material culture of memory related to contested sites, “What Still Remains: A Cultural History of Negative Heritage,” is forthcoming from University of Chicago Press.

Recently, I tripped over my own feet in downtown Berkeley, California. I was trying to read a plaque set in the pavement while walking over it, and I nearly fell into a busy intersection.

The light changed; I stayed put to read the plaque again.

Being idle in the wooden building, I opened a window.

The morning breeze and bright moon lingered together.

I thought of my native village far away, cut off by clouds and mountains.

On the little island the wailing of cold, wild geese can be faintly heard.

The hero who has lost his way can talk meaninglessly of the sword.

The poet at the end of the road can only ascend a tower.

— Anonymous Chinese immigrant detained at Angel Island

This time, I actually shivered.

The poem is arresting in its simple beauty, but also its incongruity: a 1910s verse written by a Chinese prisoner embedded in concrete in gentrified Berkeley, where it lives next to other plaques featuring works by well-known (and I noticed, mostly white) authors: Allen Ginsberg, Gertrude Stein, Jack London, Berthold Brecht and city’s namesake, Bishop George Berkeley. Together, they are part of the Berkeley Poetry Walk (2003), curated by former U.S. poet laureate and UC-Berkeley English professor Robert Haas.

The poem also arrested me because I recognized it. The anonymous Chinese immigrant’s verse has become something of a celebrity artifact, a “model fragment,” in Allan Sekula’s resonant phrase — the best known, perhaps, of many inscriptions found on the walls of a decaying “immigration center” on the nearby Angel Island. Here, just a stone’s throw from Alcatraz, thousands of newly arrived immigrants were “quarantined” in crowded barracks — for days or weeks, sometimes months or years. More than half were from China and Japan.

Such practices, fueled by anti-Asian laws stretching back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, took place on Angel Island from 1910 to 1940, later expanded across the whole West Coast “Exclusion Zone” after Pearl Harbor. Some 120,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in makeshift detention centers and then in longer-term prison “camps” in places like Topaz and Manzanar and Heart Mountain for the duration of the war. Angel Island was converted into a POW camp for Japanese captives, but it also housed Japanese immigrants taken from their homes in Hawai’i and elsewhere, thus conflating enemy combatant with noncombatant, both of whom were poorly treated.

These histories are well documented, if not much contemplated beyond West Coast and descendant communities. Anyone who visits Angel Island, which is on the National Historic Register, can learn about them and study the inscriptions on the prison walls. A common site of research and pilgrimage, it enjoys both state and federal protection — for the time being, at least.

I have explored a range of celebrity artifacts and remnant landscapes in my work on “negative heritage,” a phrase I use to describe sites and narratives associated with America’s most difficult and traumatic pasts, and which often persist as deeply stigmatized places. Sites like the former Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, where, in 1942, some 8,000 San Franciscans of Japanese descent were forced to “assemble” in makeshift barracks — and like the unnamed Chinese poet — were detained without explanation for months. Sites like Manzanar, in Independence California, where many of these were subsequently held until the end of the war, now a National Park Service-administered historic site.

(Both will be focal points in “Dislocations,” a travel course focused on the landscapes of Japanese American incarceration I am teaching with my Sam Fox colleague and collaborator, Kelley Van Dyck Murphy, this summer.)

Recently, when Tanforan was razed to make way for a shopping center, the descendant community demanded some kind of commemoration. Now, the public transit station adjacent to the site hosts an outdoor memorial (2022) and a long-term indoor exhibition (Tanforan Incarceration 1942: Resilience Behind Barbed Wire, 2023) that includes both historical narrative and artistic works. Another memorial, Patricia Wakida’s Japanese American Confinement Monument, was recently unveiled just across San Pablo Bay in Hayward, California, at a site where Japanese Americans were loaded onto buses for forced relocation.

These memorials name names (starting with the agencies of detention) and provide documentary evidence of injustices that transpired in broad daylight across the Bay Area (the outdoor memorial includes a sculpture that references the small, tar-paper barracks that would have been visible from outside the Tanforan racetrack). In this, they are more explicitly referential than the Berkely plaque, bringing not only facts but human experiences of incarceration into everyday spaces. Visitors can contemplate them before climbing into buses or trains or Ubers.

Skeptics point out that such memorials — even the most confrontational and subversive ones — often serve mainly to assuage the conscience of the powerful and elite and to domesticate trauma. (See, for example, fourth-generation Japanese American Brandon Shimoda’s discussion of the Japanese American Historical Plaza in Portland, Oregon in The Afterlife is Letting Go.) Is this what the plaque at the corner of Addison Street and Shattuck Avenue does, or has done? I am not sure it is that simple.

In my own research, I reconstruct the longer material and social histories of negative heritage to observe just how it has worked and what kind of memory has been produced at such sites. These are questions of culture and representation but also of meaning and identity — of epistemology. In answering them, I have often discovered that certain photographs and poems activate new memory — that words on a plaque can subtly reshape local imaginaries, new ways of knowing a place or an event.

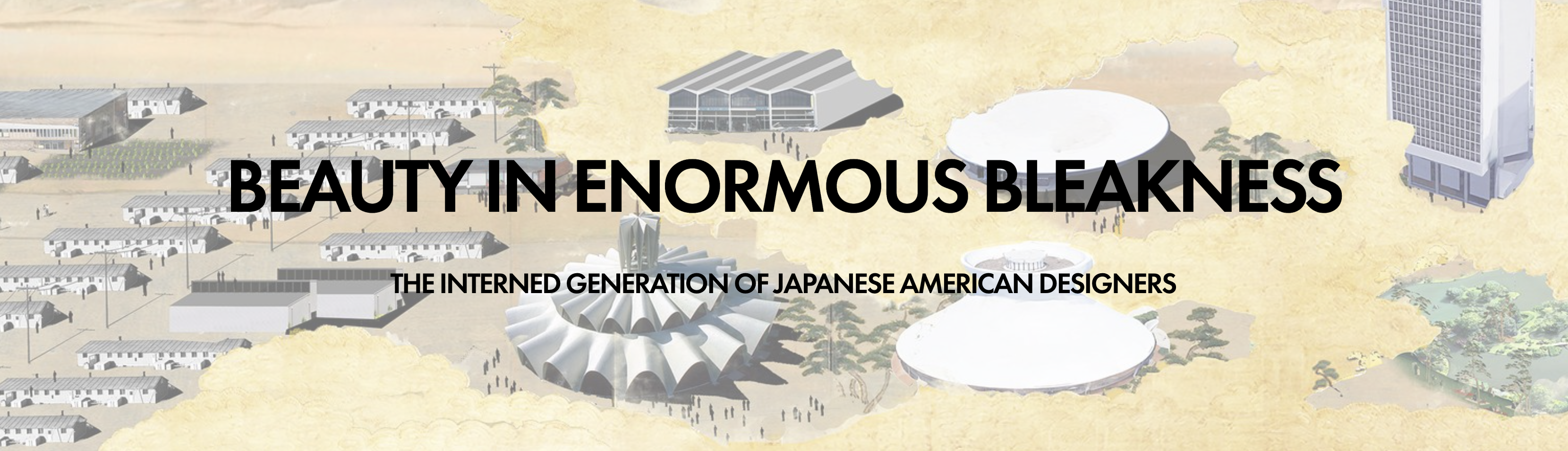

The makings of such historical imagination have also been central concerns of more public-facing work I have pursued with my collaborator Van Dyck Murphy in Beauty in Enormous Bleakness, a project that seeks to uncover hidden legacies of the Japanese American incarceration in the domain of art and design. This work seems all the more urgent, if also more fraught and painful, in this season of political turmoil. As we reimagine elements of a 2023 exhibition for installation at Lambert International Airport (set to open in 2026), we will be wrestling in particular with what it means to tell these stories in the Midwest, in a public space much like the San Bruno BART station, devoted to quick transport and uplifting design.

What does it mean to tell these stories well, with integrity and care for descendant communities, in such spaces, now, in the midst of a full-scale assault on “traditional” heritage institutions such as museums and archives and national parks, as our leaders invoke the Alien Enemies Act?

To begin, we need to resist the cynicism that often creeps into our thinking about localized, small-scale historical-interpretative projects. Plaques and memorials may be insufficient hedges against wider-scale erasure and forgetting, but they have their place, and in the years to come, we may very well need them as anchors for our work as citizen-stewards of the national past.

Headline image: Reconstructed guard tower at Manzanar National Historic Site by MPSharwood. CC BY-SA 4.0.