Laura Evers is a PhD candidate in English and American Literature. She is a career peer coach at WashU’s Center for Career Engagement and an associate editor for ‘RHINO,’ a poetry journal based in Chicago.

Can you recall when you first saw a child on campus? If you’re a parent or guardian, I invite you to think about a child who isn’t your own. My guess is that such sightings are rare, confined to visiting school groups, perhaps, or a brief passing encounter in a hallway.

Poetry workshops might seem a particularly unwelcome space for children. But that was not the case at a CRE2 event I attended this past September. When I entered the classroom, I spotted a woman holding a baby in a blanket. Beneath the woven pattern, the baby’s hand poked out, triumphant little fist squeezing my heart. Shame and bewilderment clouded the room as other participants drifted inside. I couldn’t believe it had taken over four years for me to notice a child’s presence at WashU. That I had not thought to question such absences before.

My failure to notice was unacceptable, enveloped as I am in a discipline defined by its close attention to detail, on pointing out gaps in literature. Buttressed by my dearly held sensitivities to parenthood and child-rearing, I left the workshop resolved to pay “better attention” to the world around me.

Of course, “better attention” faded in the rearview mirror along with summer. Conversations with my partner, Michael, about when to add to our family stayed off campus, where I thought they belonged. All children, real and imaginary, seemed irrelevant to my study of universities and their artistic representations.

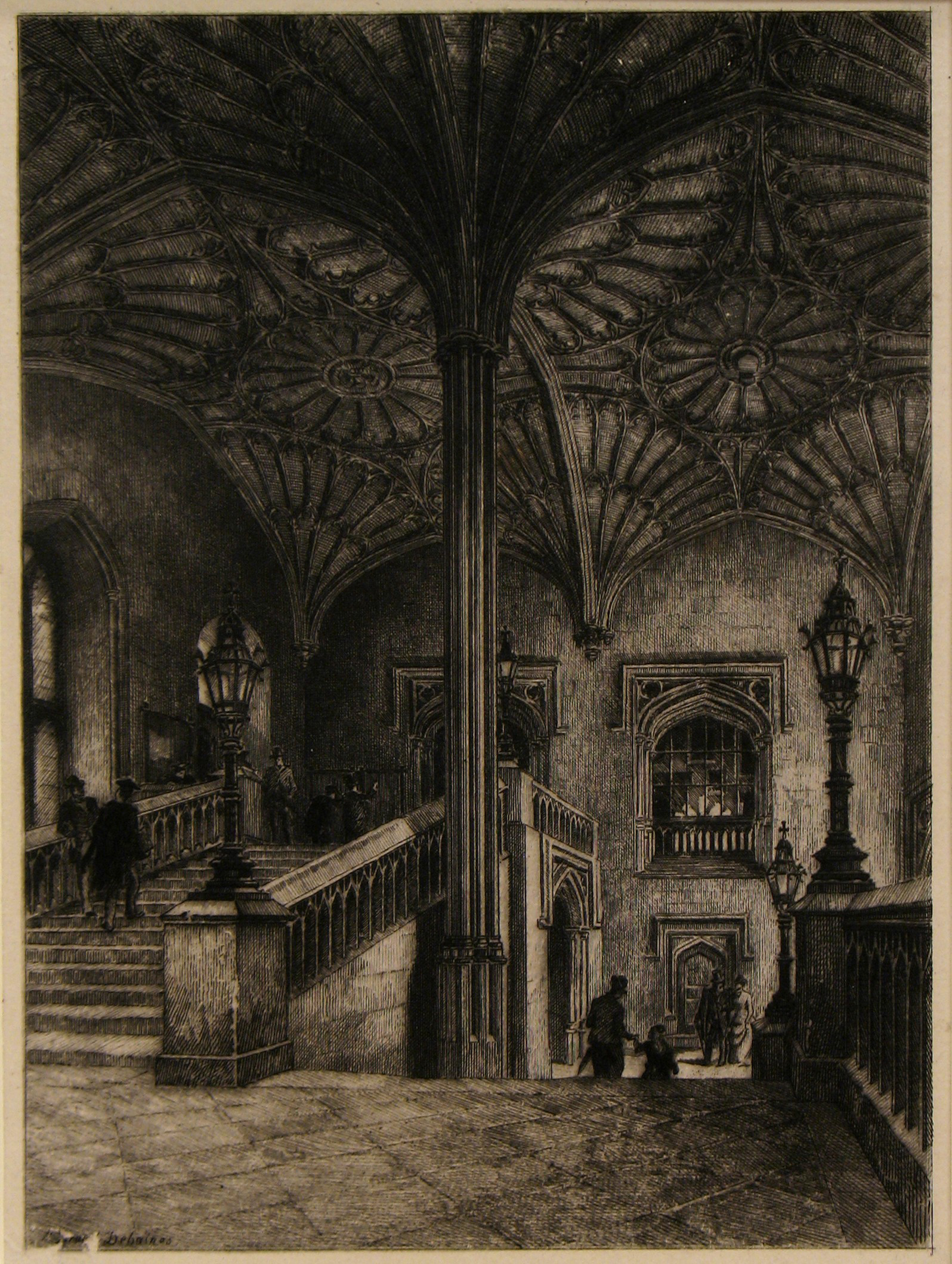

Life went on; work began on a New Perspectives Talk for the Kemper Art Museum. I had an opportunity to give a public-facing lecture about some artworks not often on view in the galleries. Fueled by my fascination with campus spaces, I selected 23 prints of Oxford and Cambridge universities made in the late 19th century for the talk.

My dissertation research on higher education and dark academia informed several assumptions I brought to the prints. Of course 19th-century Oxford and Cambridge were closed-off, cloistered and exclusive environments, where “Big Learning” unfolded for a white, Eurocentric, male, affluent few. Women, BIPOC and queer individuals, town residents or scholars from the Global South? Forget it. Few opportunities existed. Those hallowed halls of Oxford and Cambridge were also hollow. I assumed the prints would reflect that hollowness.

But the scenes surprised me. The artists chose to depict the universities of Oxford and Cambridge not as walled-off, largely inaccessible places but as communal, multiuse spaces, shared (aspirationally) among different groups. Some examples included a laborer holding the tools of his trade flanked by a Merton College arch; both men and women participating in communion; students and townspeople alike milling around outside King’s College Chapel. Fences, if there are any, are low and see-through.

Of course absent is any visual reckoning with university connections to the slave trade and colonialism. That being said, the prints depicted scenes of communality and mixed use, a mingling of peoples and sometimes even animals going about their day-to-day lives. Interpersonal dynamics unfolded in a symbiotic, if not highly idealized, harmony at the level of socioeconomic class, gender and, perhaps most unexpectedly, age.

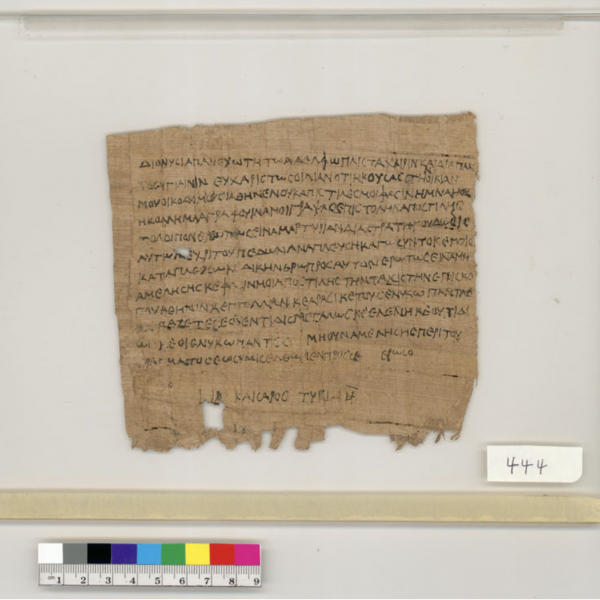

This interior print of Oxford initially caught my eye because of its “dark academia” aesthetic. In addition to the trademark Gothic architecture, the scene possesses other features: shadowy figures, smudged edges, high contrast, the agony of the liminality of the staircase. Given the smokier edges, it can be easy to overlook the people on the stairwell. But if one peers a little closer, a child emerges, holding the hand of an adult descending the stairs. The artist, Alfred-Louis Brunet-Debaines, chose to represent a child having a place at Oxford alongside adults.

When I first looked at this print, I was immediately transported back to the poetry workshop, with the blanket and the baby and the soft September light. And thanks to the workshop and the print, I was now primed to pay “better attention” to children in art. A few weeks later, Olin Special Collections screened a 1963 short film for my first-year seminar students. Titled “Once Upon a Hill... There Was a School!” WashU’s Radio, Television, and Film Office had hired Martin Lavut to direct the film in the early 1960s.

Writing about the grant to preserve “Once Upon a Hill...” WashU archivist Sonya Rooney and Curator of Film and Media Andy Uhrich detail how “the film follows students throughout their day as they wake up in their dorms, flirt over breakfast at a raucous cafeteria, are excited and confounded by a professor’s lecture, study in the new Olin library, and engage in student activities like judo. It is equal parts a subjective view of the exhilarating experience of campus life from the students’ vantage point and a clinical outsider analysis of the average American college student.”

Highly stylized and rhythmic, and lacking diegetic sound and music, this fascinating documentary, so focused on the perspective of an “average American college student,” surprises its audience by taking a sharp turn away from its student protagonist at the end. Instead, the closing scene shows children playing beneath different sections of the athletic field bleachers. Two boys climb a WOMEN sign, while others strike a pose. The children are unaware of how the institution has designated who can and cannot play in that space. They defy several rules, dangling haphazardly.

A liability today to be sure, as WashU’s Youth Protection Policy reminds us. The University of Missouri at St. Louis’ policy, titled Children on Campus, is slightly more forgiving. But both documents position children, at best, as tolerated distractions for the sake of their parents or guardians and, at worst, a lawsuit.

By contrast, a Children’s Studies minor at WashU, with routinely waitlisted literature classes at the vanguard, marks childhood, quite rightly, as worthy of rigorous study and inquiry. The minor encourages undergraduate students to volunteer with children. Support groups like Cub Club empower parents to bring their kids and meet and mingle. I don’t have space to list every policy and initiative here, but the evidence shows there are different ideologies regarding how children can best be present on campus.

To craft the New Perspectives Talk, my research had started with the question, “How have artists shaped representations of who and what university spaces are for?” The prints and film I encountered were interested, however imperfectly, in suggesting universities could be a place for children. From these works of art emerged a deeper question, a question I continue to carry close to my chest as I walk across the grounds of WashU, a question that leverages the power of our imaginations: “What does our campus look and feel like from the perspective of children?”

Headline image: Students walk on campus on a fall afternoon at WashU by James Byard/WashU.