Meredith Kelling is the assistant director of student research and engagement in the Center for the Humanities. A scholar of 20th-century American women’s writing, she earned a PhD in 2021 from Washington University’s Department of English. Her dissertation, “Passable,” examined midcentury Black and leftist women’s texts that have been overlooked because of their attachments to women’s and domestic work — realms wrongly regarded as politically acquiescent and intellectually inferior.

RELATED EXHIBIT - ON VIEW THRU NOVEMBER 4

Fire and Freedom: Food and Enslavement in Early America

Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110

Please email to arrange an in-person viewing, or visit the National Library of Medicine’s companion website online.

Few human acts carry more symbolic power than eating. As a species, food — its production, preparation and consumption — is the material around which we arrange so many social norms and cultural traditions. All food, memorable or not, is labor, even the banal stuff we nosh on just to get through our days. The durational toil of planting and rearing plants and animals; the incredible efforts of harvesting, fishing and slaughtering; the mental acuity required to identify and gather edibles in the wild; the confusion of shopping for ingredients and plugging them into a meal plan; the dexterity required for the knife, the boiling pot, the stove; the emotional efforts of serving food to others; the patience for cleaning up a kitchen or a table; the cunning necessary to stretch leftover food into later meals — all of these are contained in our quotidian acts of consumption.

It is terribly easy to overlook such labor in the rush of modern daily life. The fast food industry, for example, has long bet on our need to feed ourselves quickly and cheaply outweighing our ability to make moral decisions about our diets. A significant amount of this willful ignorance seems forgivable, especially on behalf of people who — squeezed out of money and time — still need from a daily meal the same rush of pleasure associated with taste and rest that anyone has ever needed from their food. But what is worrying is how the demands on the plate — for rest, respite, and pleasure — imply much greater demands on unseen others.

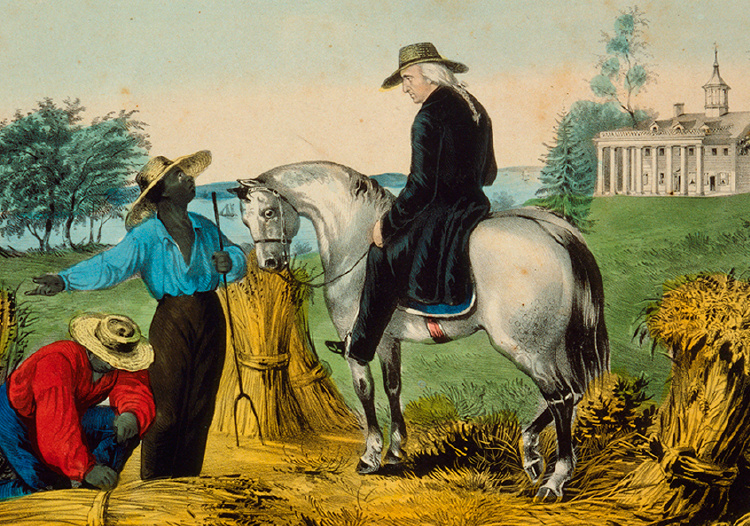

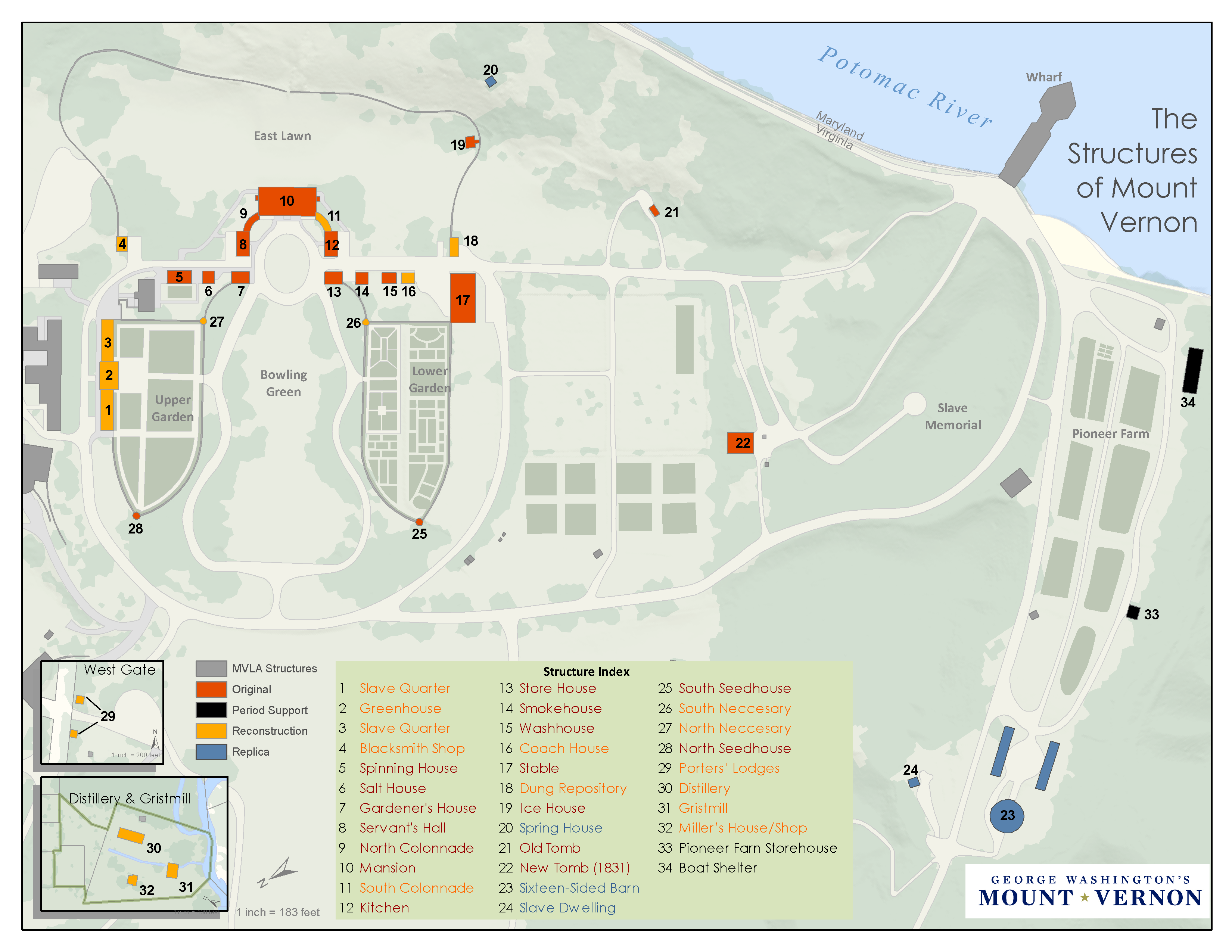

Produced by the National Library of Medicine and guest curated by Psyche Williams-Forson, Fire and Freedom: Food and Enslavement in Early America (a traveling exhibit currently on view at the Washington University Medical School’s Becker Medical Library) condenses a relationship between food and power to a manageable scale: foodways at Mount Vernon, George Washington’s plantation estate.

Williams-Forson traces an important connection between labor and abundance at the Washington table. In the kitchen, enslaved cooks worked long hours over fires, their blunt, pre-modern equipment requiring a superhuman amount of precision and attention despite the precarity of their lives under the white supremacist household regime. In the fields, woods and waterways, more enslaved folks toiled to raise fruits and grains, source fishes and game and harvest crops. In the house, enslaved servants attended to every detail to meet the Washington standards for cleanliness and propriety, even as they were themselves deemed subhuman and unclean. This work — beginning before dawn and ending long after sunset — structured life at Mount Vernon, nourishing the plantation’s owners and providing them with a forum for receiving and discoursing with other powerful people.

As is true of all plantations in the American South before emancipation, human trafficking at Mount Vernon was operationally essential. Without the exploitation of African workers and their descendants, the compartmentalization of field, kitchen and dining room according to race and gender could not have taken place. It stands to reason that George or Martha Washington’s seemingly innocent desires for a cup of tea or a specific dish were also appetites for violence. The exhibit is most forceful on the point that “slavery was never benevolent nor kind.” For enslaved people engaged in what has often been interpreted as milder domestic work compared to field work, the kitchen was hell. It could hardly satisfy a skilled cook to know that whatever delicacies they sweated over went straight into the mouths of their oppressors. (Washington’s prized chef, Hercules, the exhibit points out, successfully escaped bondage on Washington’s 65th birthday.)

Williams-Forson has written much about food, gender and race. Her 2006 book, Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power, is a meticulous examination of Black women’s culinary labors for signs of their culinary genius, cultural knowledge, care and activist networks, and expressive power. In Williams-Forson’s hands, the chicken leg is a clue pointing us toward the richness of Black women’s lives, where systemic erasures — enforced illiteracy and disenfranchisement; poor health outcomes guaranteed by racial segregation and gender bias; relentless, centuries-long conscription of Black workers into domestic work no matter their desire or ability; and general historiographical bias against women, Black people and the poor — make for a comparatively thin historical record. [The video below details the excavation of Mount Vernon’s earliest kitchen. Sites such as these, in contrast to the dwellings of the enslavers, are at most risk of being erased from the historical record.]

It is no coincidence that the work of learning about enslaved inhabitants of American plantations necessitates excavation and archeological method, so buried are these histories, so precarious are their extant traces. In following the “trail of chicken bones,” Williams-Forson forces us to reread other, more established archives that document the design of the new republic, documents and letters that call for liberty and equality on behalf of men whose intellectual pursuits were nourished through exploitation of a very personal and everyday nature. The trail of chicken bones to Mount Vernon reveals a subtext of those framing documents: both nourishment and liberty are achieved through oppression.

Headline image by Annie Spratt via Unsplash