Zhao Ma is associate professor of modern Chinese history and culture in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. His work on China’s presence at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair is part of a larger project, “Global Qing and Its Legacies,” which explores the manner in which Qing ideas, institutions and behaviors have participated in making and remaking the modern world.

On June 26, 1903, the Japanese steamer Hong Kong Maru completed its long journey across the Pacific Ocean and arrived safely at the port of San Francisco. Among the passengers disembarking were Chinese diplomat Wong Kai Kah (1860-1906) and his family. Wong served as the Chinese Imperial Vice Commissioner to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. He arrived in the United States nearly one year before the exposition opened to the public, on a mission to coordinate preparations and oversee the construction of the official Chinese pavilion. After a brief stay in San Francisco, Wong and his family boarded a transcontinental train. They arrived in St. Louis on July 3, ending the month-long journey from the capital of China to the heartland of America. Reporters from local and national newspapers showed interest in these foreign guests. They followed Wong as he went visiting the fairgrounds and holding meeting with fair organizers, local officials and business leaders. Wong’s wife earned her share of attention from the media sometimes by her words (in interviews and through her husband’s interpretation) and more often by her wardrobe. The Wongs “had with them 150 trunks containing their clothes,” and she “has brought with her no less than 200 gowns, all different.” Many of them [gowns] are worth from $400 to $700 apiece” (about $14,100 to $24,800 according to one online inflation converter).

What reporters did not mention in the newspapers — but what fascinates me — is: Who took care of the Chinese dignitaries’ precious wardrobe — folding and cleaning their gowns, carrying those trunks? The Wongs also traveled with their children. So, who handled tasks like making beds, doing laundry, preparing meals and running errands? Who kept the household running when they socialized with prominent members of St. Louis high society? The search for answers shifts the focus of my research from Qing royals and Chinese diplomats to another group of individuals who journeyed to attend the exposition. These include assistants and interpreters tasked with serving officials and their families, workmen (such as painters, carpenters and carvers) who came to erect the Chinese pavilion, and merchants and their assistants who brought goods to furnish the Chinese exhibition. Though they remained out of the media spotlight and were often overlooked by later historians, these individuals played a crucial role in facilitating or directly supporting the Chinese mission at the exposition.

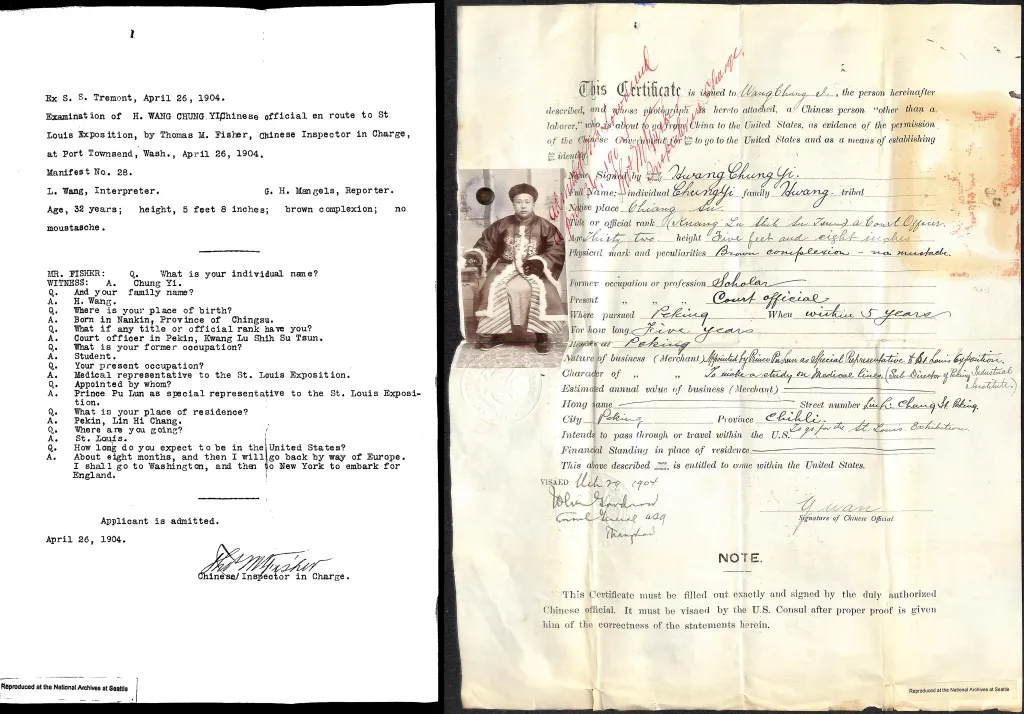

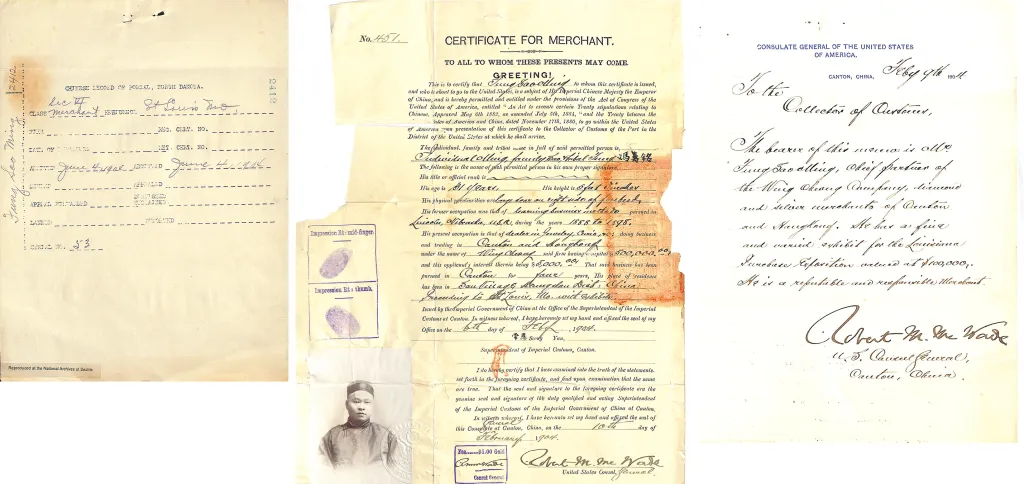

Their experience becomes even more extraordinary when considering the arduous circumstances under which they made their journey across the Pacific Ocean and then from America’s West Coast to the heartland. They traveled during the era of Chinese Exclusion, when federal law prohibited all Chinese laborers from entering the United States and barred those already in the country from obtaining citizenship. Although Chinese merchants, teachers, students, diplomats and travelers were exempt from the exclusion, they still fell victim to the pervasive “culture of exclusion” that had infested the entire immigration administration, from legislators and bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., to the agents placed at each port of entry. Upon arrival at the border and once entering the country, Chinese travelers faced draconian and discriminatory measures, i.e., the “means of inspecting, processing, admitting, tracking, punishing, and deporting immigrants in the United States,” rigorously enforced by the federal agencies and state and local law enforcement. These policies and practices effectively turned America into a “gatekeeping nation,” as historian Erika Lee aptly describes.

Hundreds of Chinese, mostly merchant exhibitors and workmen, attempted to come to America to participate in the exposition in St. Louis against the odds of the exclusion. Chinese were required to submit a certificate to immigration officials at the port of entry to prove their identity, provide photographs in triplicate and post a $500 bond. Once admitted to the United States, they should “proceed immediately, by direct and continuous travel,” to the exposition. The Bureau of Immigration officials at the exposition were tasked with compiling a detailed list of all Chinese persons, including their name, sex, age, employer, job duties, work hours, arrival and departure dates from the exposition, as well as the person’s signature and photographs, and the examiner’s signature. If a Chinese person planned to leave the fairgrounds temporarily, he was to be issued “a dated card” with his name and other information of identification and required to return within 12 hours. Within 30 days after the exposition’s conclusion, Chinese persons were required “by direct and continuous travel to the port at which he was admitted and hence depart, by the first vessel sailing thereafter, to China or to the country of which he is a citizen of subject.” Failure to leave the exposition and United States would result in prosecution under the exclusion laws, forfeiture of the bond and deportation. The journey of Chinese workmen and merchant exhibitors remind us that, besides royals and dignitaries, millions of people from all over the world made their way to the exposition. The journey was not always pleasant though. Many faced restrictions and experienced harassment.

What do we make of the Chinese experience in the 1904 World’s Fair and the US–China relations at the turn of the 20th century? According to American politicians and fair officials, China as a country had to be included and integrated into the global system of colonialism and capitalism. Losing access to the Chinese market, or being outcompeted by other European powers and the rising Japanese empire, would jeopardize American security and prosperity in the new century. If inviting the Wongs as diplomatic representatives of China to take part in the World’s Fair represented a “polite” gesture of America’s imperialist benevolence, to scrutinize and even deport Chinese workmen and merchant exhibitors under the Chinese Exclusion Act represented a “vulgar” form of racism. Such blatant racism, conceived on biological determinism and social Darwinism, regarded all nonwhite indigenous and minority subjects, Chinese included, as sub-humans and a threat to the white race and western civilization. Without the possibility of assimilation, they were to be studied, observed, categorized, quarantined, conquered and kept away.

Headline image: View of the Chinese pavilion at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. The exhibit represented China’s debut on the Western world stage. Photo courtesy Missouri Historical Society.