Four days after the opening reception of the exhibition Higher Ground: Honoring Washington Park Cemetery Its People and Place, collaborators Jennifer Colten (senior lecturer, School of Art), Denise Ward-Brown (associate professor of art, School of Art) and Michael Allen (University College coordinator and lecturer, American Culture Studies; and senior lecturer, Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Sam Fox School) sat down to talk about their research and the issues the exhibition seeks to unveil.

With photographs, video and oral histories, and an art installation, their exhibition (along with artist Dail Chambers and landscape architect/essayist Azzurra Cox) tells the story of Washington Park Cemetery, a once-bucolic cemetery for African Americans established in 1920 that eventually fell into disrepair following decades of successive blows that follow a too-familiar history of social injustice, racial politics and neglect. In his catalog essay that accompanies the exhibition, Allen writes, “The landscape’s fate seemed a metaphor for the changes that north county itself was enduring, as it passed from edenic ideals to profane realities.”

What follows is a short excerpt from that conversation.

We’ve started to understand that better. It's like the art has gone from lament toward justice, sort of a different epoch in the story.

JEN: I think that's really important and kind of parallels the exhibition. I always had an interest in the acknowledgement of history, and time, and culture, but the art carrying a voice toward justice was not something that I had in the forefront of my mind then. I think that's an important development in my thinking today.

DENISE: When I look at your photographs, Jen, I see a melancholy. The images are so poignantly beautiful.

JEN: There is a loss that I am acknowledging. There were people at the exhibition on opening night who told me that they felt like crying. There were also people who said they were really angry. They were moved in that way because the melancholy is real, but it shouldn't be confused with nostalgia. I hope what they feel is more a motivating association with loss and injustice.

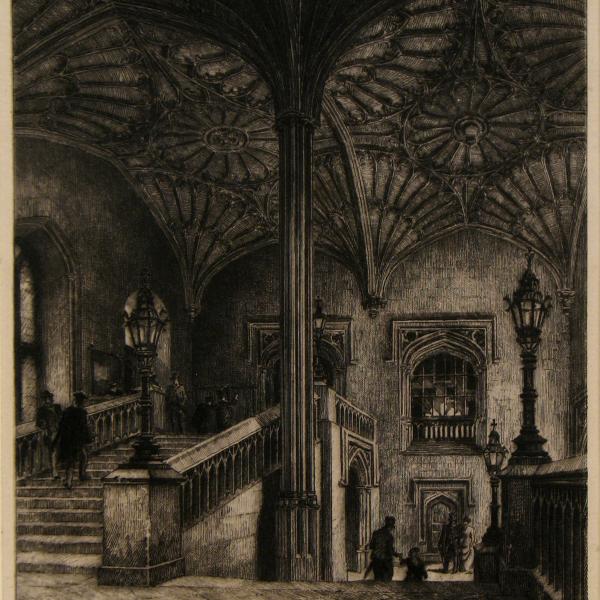

DENISE: One of my friends pulled me aside to look at a photograph in the first room of the grave that had been moved three times. It really moved him. He thought that that was the epitome of all the photographs.

![WPC Section 14. [113.13], 1993. Digital print from original negative by Jennifer Colten. The engraving reads: “In memory of those who were originally interred in Potters’ Field located in the City of St. Louis prior to 1950 and reinterred in a portion in Mount Lebanon Cemetery thereafter. Reinterred this site June 1986. ‘May they rest in everlasting peace’.”](/files/cenhum/imce/2_wpc_113.93.13_small.jpg)

JEN: That stone memorializes the people who were interred in a Potter’s Field. They were moved, and then moved again, and then clearly the stone is washing away. It is symbolic of the repeated forms of erasure that have happened — the conditions at Washington Park Cemetery are only one example — the repeated and multiple forms of cultural erasure are revealed in this one photograph…

It’s remarkable to me how many African-American people from St. Louis tell me they have somebody buried there. I am just amazed at how big this cemetery was.

MICHAEL: I didn’t know that until I started working on this project. It sort of touches every corner of the region. Not just this side of the river, but many families in East St. Louis, in that area in St. Clair County buried relatives in Washington Park Cemetery.

DENISE: The words of some of the people I interviewed, gave me a fuller understanding of what this place was to the community. John Parker said they opened up that cemetery just because Kinloch was across the road.

MICHAEL: Kinloch’s geography established sort of the potential growing black suburb, right?

JEN: Michael, you probably know this history. Was Kinloch a developing, thriving, promising community at that time?

MICHAEL: Oh, yes. It was going toe to toe with Ferguson, Webster Groves. I mean, it was a desirable community suburb.

DENISE: John Parker said that it was the Harlem of St. Louis.

MICHAEL: Families were leaving The Ville to live in Kinloch. Partially to escape what was already being perceived as this constant pattern of displacement. You could leave the city. You could get out to Kinloch, have your own land, be in the suburbs, live the American dream.

MICHAEL: Families were leaving The Ville to live in Kinloch. Partially to escape what was already being perceived as this constant pattern of displacement. You could leave the city. You could get out to Kinloch, have your own land, be in the suburbs, live the American dream.

DENISE: It was marketed to black people. They had their own fire department, police, hospital, everything. It was like The Ville, but it was in the suburbs so…

MICHAEL: Sadly, Kinloch’s history isn't as celebrated as The Ville’s. Kinloch has only now starting to capture more historic interest.

DENISE: I think it's because it’s … I don't know the whole story of Kinloch, but it’s just been so ravaged.

MICHAEL: It’s almost completely erased. It sort of has this parallel with the cemetery, although the cemetery has a potentially more hopeful future.

JEN: Denise, after completing your research and interviews, what is your reflection on the place and the people?

DENISE: All the people I talked to, especially the volunteers, find the place a sacred space. That's the reason they’re out there. They have some attraction to the place because they know the importance of family and ancestors. In many ways I feel the same way. I think it’s one of the most beautiful places in all of St. Louis . . .

There are just so many beautiful stones and beautiful places. When I first went there, I was mostly lost. Then, when I was editing near the end, I’m like, “Oh, look at that. Those were the same places.” I know exactly how to get there now.

JEN: I know. When I was titling the photographs — back when I originally made them, I only had titles that referred to my own cataloging system — today in titling them, I attached the section number to the title. It was really amazing that I could remember that specificity from so long ago. Just as you say, eventually you learned the geography of the place. The cemetery is potent with its geography. Potent might not be the right word, but it’s distinct.

All photographs by Jennifer Colten. Read Michael Allen’s Higher Ground catalog essay here.

Artists’ Talk

Higher Ground: Honoring Washington Park Cemetery Its People and Place

Friday, April 7, 6 pm

The Sheldon Concert Hall and Art Galleries, 3648 Washington Blvd., St. Louis, 63108

Featuring project artists Denise Ward-Brown, Jennifer Colten and Dail Chambers. Admission is free, but reservations are required. Contact Paula Lincoln at plincoln@thesheldon.org or 314-533-9900.

http://www.thesheldon.org/current-exhibits.php

Panel Discussion

Higher Ground: Honoring the Story of Washington Park Cemetery

Featuring project artists Jennifer Colten, Denise Ward-Brown and Dail Chambers, as well as catalogue essayist Michael Allen, director of the Preservation Research Office. Moderated by Missouri History Museum curator Gwen Moore. The panelists will illuminate the history of Washington Park Cemetery and discuss the process of honoring its history in an exhibition.

Wednesday, May 24, 6:30 pm

Missouri History Museum, Lee Auditorium, 5700 Lindell Blvd., St. Louis, 63112

http://mohistory.org/node/58716