Interview with African-American studies scholar Jonathan Fenderson

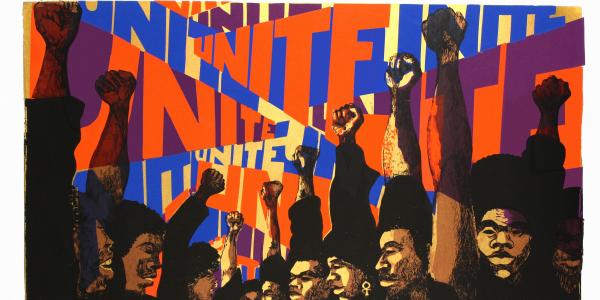

“The black revolt is as palpable in letters as it is in the streets,” begins the seminal 1968 essay “Towards a Black Aesthetic.” Its author, Hoyt Fuller, was a pivotal figure in the African-American intellectual culture of the 1960s and ’70s and is the subject of Faculty Fellow Jonathan Fenderson’s current book-in-progress.

“‘Toward a Black Aesthetic’ and, more important, the concept have remained a touchstone for thinking about African-American literature (and literary politics) of the 1960s and 1970s,” says Fenderson, who is an assistant professor of African and African-American studies. “In fact, it was this essay that first sparked my interest in his life. I realized that I had encountered that essay on numerous occasions and in several classes but never read anything about his broader life and work. From there, I set out on an intellectual journey to learn more about him.”

Read on for a preview of Fenderson’s project, “Building the Black Arts Movement: Hoyt Fuller and 1960s Cultural Politics.”

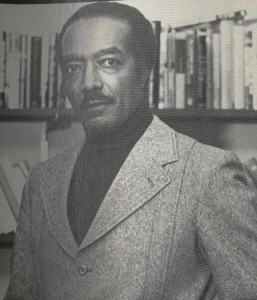

Your book explores activist and organizer Hoyt W. Fuller and the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s. Who was Fuller, and why did you focus on him? What was his role in the movement?

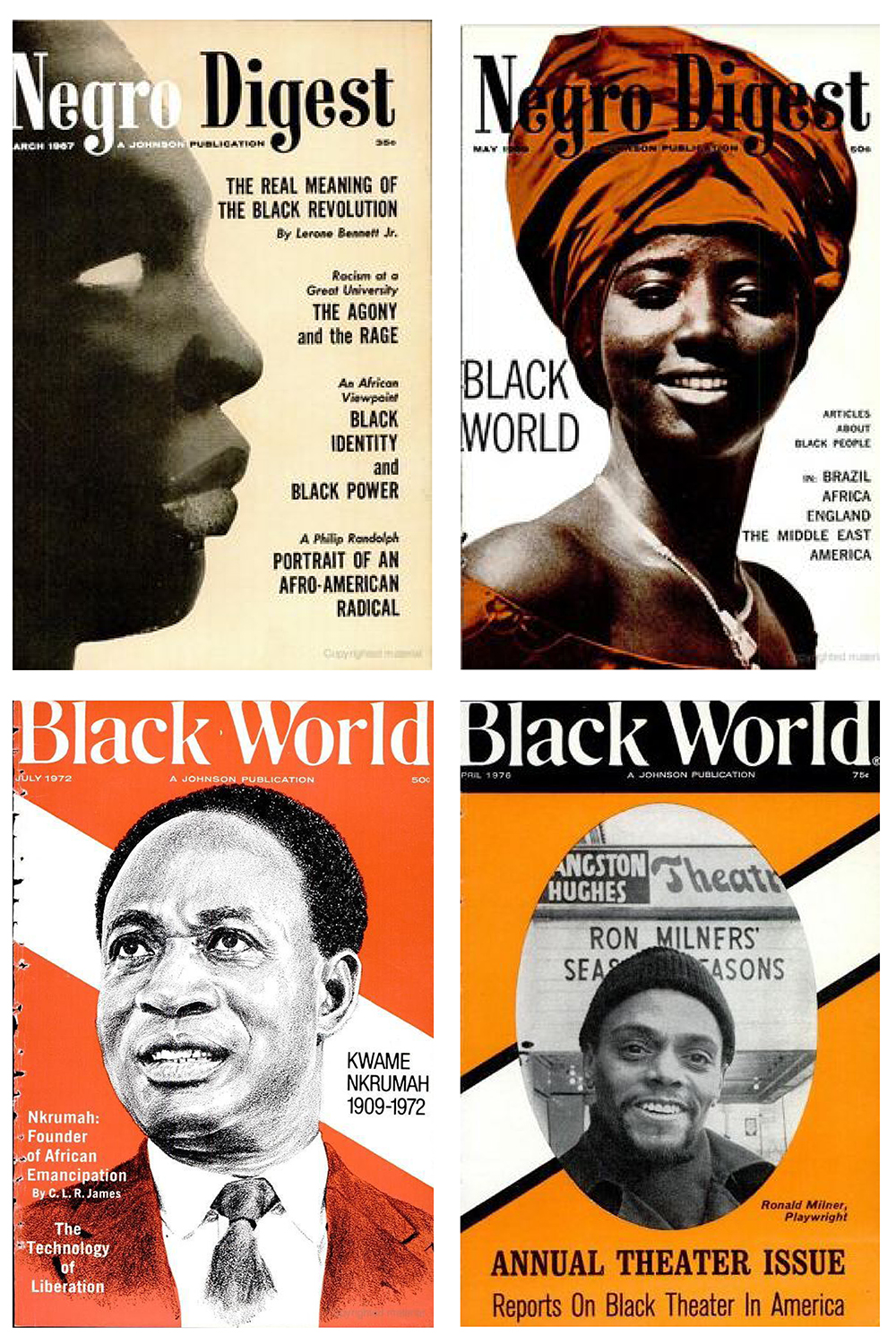

Hoyt Fuller was an editor, activist and intellectual who profoundly influenced African-American counterpublic discourse immediately after Jim Crow in the 1960s and 1970s. He edited a widely read journal called Negro Digest, which he later renamed Black World in 1970. He ran the journal from 1961–76, using it as the most important monthly print platform for the Black Arts Movement and African-American intellectual culture.

It was through his work with Negro Digest/Black World that participants in the Black Arts Movement began to understand themselves as a national network of like-minded individuals and organizations. Fuller was also an activist who was obsessed with connecting local struggles with larger global fights for liberation. Situated in Chicago for most of his career, he was part of a triumvirate that founded the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), a community-rooted artistic and intellectual collective that sparked national trends in the area of African-American literature and visual arts

At the same time, Fuller pushed the local group to participate in Pan-African organizing efforts on the African continent. Between 1966 and 1977, Fuller attended and participated in several international cultural festivals on the African continent, including the first World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal in 1966, the first Pan African Cultural Festival in Algiers, Algeria in 1969, and the second World Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture in Lagos, Nigeria in 1977.

In this sense, he was a cosmopolitan black activist, who believed that the fate of black people throughout the diaspora was tied to that of Africa.

Fuller was also an intellectual in his own right. He wrote newspaper articles, long-form essays and editorials and published a short Pan-Africanist travelogue, titled Journey To Africa, that chronicled his experiences in Morocco, Senegal, Algeria and Guinea.

What new contribution to your field does this project make?

This book is an attempt to think through the ways mid-20th-century shifts in America’s (and the broader world’s) economic, racial and cultural terrains influenced African-American life.

How did these shifts make black people think differently about themselves? How did the shifting terrain destabilize long held beliefs in the African-American community? And, more important, how did this shifting terrain produce new, innovative ideas that would subsequently emerge as core pillars in the African-American culture. Many scholars have wrestled with these questions; however, my book uses Hoyt Fuller’s life as a prism to interrogate these issues.

How does this project fit with your overall research interests?

For some time now, I’ve been fascinated by African-American intellectual history and politics in the 1960s and early 1970s. This was truly a turning point for black Americans — and the country at large. Much of what we’ve seen subsequently in the “culture wars,” the rise of the Reagan Right, the hegemony of neoliberalism, all find their roots in that moment. So, this book is my first take on trying to think through that moment. My next book will continue this same path, though I hope to move away from questions of culture and instead prioritize the intra-racial politics of class.

What kinds of sources are you using in your research? Where did you conduct your research?

I've done dozens of oral history interviews with several of his most trusted allies, colleagues, contributors to the magazine and artists and intellectuals who were generally active during the period. Those interviews have helped me fill in numerous gaps in the archival record. And it's my hope that the book adequately captures those voices.

Ironically, Fuller's family knew very little about his public life. And I talk about this a little in the book. When he passed, they were, for the first time, learning of his national importance. His family had no idea how important he was until people like James Baldwin showed up to his public funeral service. So the irony is, his family — the people we would assume were close to him — knew very little about his career.

My main archive is the Robert Woodruff Library at Atlanta University. They house the Hoyt Fuller Papers and several other tremendous collections in their archive. It's a world-class institution and a first-rate archive. I could not have completed this project were it not for the Woodruff and the incredible staff that keep that place functioning at such a high level. I have also tracked down sources in Nigeria and the UK.

In what ways do we see the impact of Fuller and the Black Arts Movement today?

At present, the United States finds itself in a moment of economic and racial crisis, much like the 1960s. We are seeing an upsurge in grassroots political activity among African Americans. Studying this period allows us to glean lessons from the past. And I believe it is particularly important to understand the ways shifting terrains impact and, perhaps more important, undermine black social movements.