Erin McGlothlin is the Gloria M. Goldstein Professor of Holocaust Studies, professor of German and Jewish studies, and vice dean of undergraduate affairs in the College of Arts & Sciences.

In 2020, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting Holocaust survivors and raising Holocaust awareness, conducted a survey of Holocaust knowledge among American Millennials and Gen Z. Among other findings, the study discovered that only 1% of respondents could correctly identify Treblinka, the National Socialist killing center in German-occupied Poland at which at which between 800,000 and 900,000 mostly Polish Jews and an unknown number of Romani were killed. On the other hand, 44% of respondents were able to identify Auschwitz, the infamous concentration camp and killing center in Nazi-occupied Poland, at which hundreds of thousands of people were imprisoned and over a million Jews and 100,000 Romani, Soviet prisoners of war and non-Jews from Poland and other countries were murdered. Yet, when media outlets expressed understandable shock about the lack of contemporary awareness about the Holocaust, they focused on the latter figure rather than the former one; after all, for many decades after the war, Auschwitz dominated in the public understanding of the Holocaust as a metaphor for evil in the modern era and as a stand-in for the totality of the complex, diverse and geographically expansive events that constituted the genocide of Europe’s Jews. Not knowing about Auschwitz, the media response implied, is tantamount to not knowing about the Holocaust in general.

Less notice was taken of the tiny number of younger adults who had heard of Treblinka, a lack of attention that reflects the relative obscurity in American consciousness of this vitally important site of genocide. Together with the killing centers Bełżec and Sobibór, Treblinka was part of Nazi Germany’s Operation Reinhard program, which, during the brief period of its operation (spring 1942 to fall 1943), aimed to systematically murder the Jews of Poland. In fact, Operation Reinhard was responsible for the most intensive killing surge during the Holocaust. Within a single three-month period from August to October 1942, nearly 1.5 million Jews (approximately 25% of the total number of Jews killed in the six years of World War II) were murdered at these three killing centers, making the program what Lewi Stone terms “the largest single murder campaign within the Holocaust.” Yet, despite their centrality to the history of the genocide, the Operation Reinhard extermination camps in general — and Treblinka in particular — are almost completely unknown to contemporary Americans.

Americans’ lack of knowledge about Treblinka is, however, not a new phenomenon. While there has been a great abundance of historical studies, survivor testimony and popular literature and film about Auschwitz reaching back to the first postwar decades, until recently there were few historical studies and almost no literary or filmic representations about Treblinka. Contemporary Americans know even less about Treblinka than they do Auschwitz, because Treblinka has for the most part remained an unexplored dimension of the Holocaust.

A number of historical and cultural factors are responsible for the comparative notoriety of Auschwitz and anonymity of Treblinka in public consciousness. Foremost among them is the comparatively large number of surviving witnesses of Auschwitz who were able to testify at war’s end about their brutal treatment and their distress at seeing their relatives murdered in the gas chambers there. While the sheer number of people who were murdered at Auschwitz made it the killing center with the highest death toll, there was also a large proportion of survivors. Scholars estimate that tens of thousands of prisoners who were registered at Auschwitz survived, along with many more tens of thousands who passed briefly through the camp. This survival rate can be attributed to the particular character of Auschwitz, the only National Socialist killing center to be located within a vast labor camp complex. Those who arrived at Auschwitz with one of the transports had a small chance of being selected to work in Auschwitz or being shipped further to another labor or concentration camp.

By contrast, Treblinka was exclusively an installation of murder and for that reason interned only several hundred Jewish prisoners at any given time as laborers in direct support of the death process. The vast majority of people deported to Treblinka was murdered immediately, while the number of people who survived is miniscule. Sources estimate that fewer than 70 people survived Treblinka, most of whom escaped in a prisoner uprising that took place on August 2, 1943. And many of those who did survive Treblinka did not survive the war, meaning that there were relatively few witnesses at war’s end who could testify to the nature of this camp.

Further, Auschwitz held at the time of its dissolution and liberation a high ratio of prisoners from Hungary and Western Europe, in contrast to the Operation Reinhard camps, at which mostly Polish Jews were murdered. Many of the Auschwitz prisoners who eventually survived either returned to their countries of origin or emigrated to other Western countries. When they began to write memoirs of their experiences, their narratives were often circulated in the West, making the Auschwitz experience widely known west of the Iron Curtain.

The few survivors of Treblinka and the other Operation Reinhard killing centers, on the other hand, many of whom spoke Yiddish as their native language, often spent the remainder of the war in hiding in Poland. After liberation and war’s end many of them remained, at least initially, behind the Iron Curtain; their testimonies, published chiefly in Polish and Yiddish, were rarely circulated in the West. Narratives of the survival of Treblinka and the other Operation Reinhard killing centers were thus much less ubiquitous and circulated much less widely in the West than did narratives of the Auschwitz experience.

In this way, two interrelated factors — the significant difference in the number of survivors of Auschwitz versus that of Treblinka and the relative prominence of Auschwitz narratives in comparison to testimony about Treblinka — have resulted in a situation in which the latter extermination camp is virtually unknown in American cultural consciousness. If only 1% of younger adults know about Treblinka, it is because we as a larger culture have not truly acknowledged and informed ourselves about it.

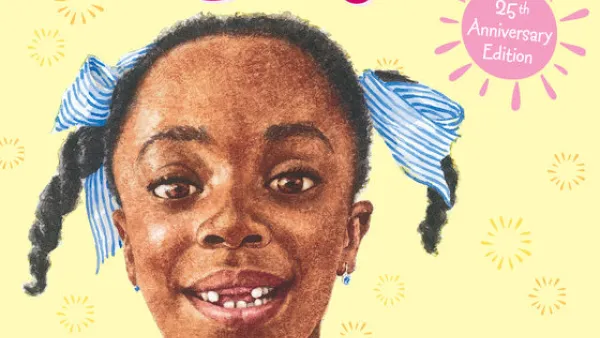

Headline image: Memorial at the site of the former National Socialist killing center at Treblinka. Photo by Adrian Grycuk.