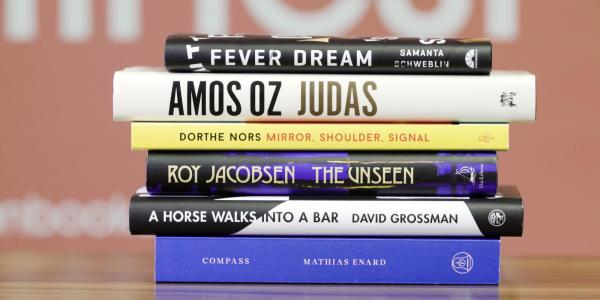

The 2017 Man Booker International Prize — which celebrates the finest translated fiction from around the world — shortlisted two Israeli works, Amos Oz’s “Judas” and David Grossman’s “A Horse Walks Into a Bar,” which ultimately won the award. Israeli literature, now 70 years in the making, has come into its own, writes scholar Nancy Berg.

At 70, Israeli literature is having its day in the sun: David Grossman won the Man Booker Prize for his novel A Horse Walks Into a Bar (with his translator Jessica Cohen); Amos Oz has won the inaugural Jingdong Literary Prize; his novel Judas (short-listed for the Booker) along with Ayelet Gundar-Goshen’s Waking Lions are both up for the 2018 International Dublin Literary Award; and the literature has been translated into 70 languages and has taken root abroad as well as in Israel.

This is a literature we have witnessed developing in real time. A literature of a new nation that consciously constructed its culture, written — mostly, although not exclusively — in a language revived after centuries of dormancy. The literature played a huge role in this unprecedented linguistic feat, anticipating and shaping the spoken language, written by non-natives and at times non-speakers.

For most of the last millennium Hebrew had fallen into disuse as the daily vernacular. While it continued to function in the religious realm it was no one’s mother tongue, and was not spoken in normal everyday conversation. The lexicon was limited to approximately 7000 items (compare with approximately 1 million in English); the literature — as it was — mostly legal or liturgical. There were no textbooks, teachers or grammars. And there was no precedent. In the history of humankind, no language that had been as dormant as Hebrew and for as long had ever been fully woken from its deep sleep.

Reviving the language presented an enormous challenge. It was in the literature that the language was forced to stretch and bend. And it is from the literature that the spoken idiom emerged, an idiom that is now the mother tongue and primary language of several million people, a language that has produced an extraordinary literature — with a great deal of ordinary works, too — in a relatively short time. Israeli literature also includes works in other languages, languages of the immigrants and indigenous, transplants and replants. It is religious and secular, refined and profane, canonical and marginal, lush and spare.

Israel claims the highest per capita book buying population and the second highest per capita publishing of books. While the marketplace is full of works translated to Hebrew from many languages, translations are now outsold by original Hebrew literature.

The history and morphology of Hebrew facilitate references to biblical stories, Talmudic discussions and prayers that many writers have exploited to enrich their work. Others have sought to liberate themselves from the tyranny of allusion, attempting to normalize the language.

The best-known Israeli poet, the late Yehudah Amichai, managed to do both:

When I banged my head on the door,

I screamed, ''My head, my head,''

and I screamed, ''Door, door,''

and I didn't scream ''Mama'' and I didn't scream ''God.''And I didn't prophesy a world at the End of Days

where there will be no more heads and doors.When you stroked my head,

I whispered, 'My head, my head,''

and I whispered, ''Your hand, your hand,''

and I didn't whisper ''Mama'' or ''God.''And I didn't have miraculous visions of hands stroking heads in the heavens

as they split wide open.Whatever I scream or say or whisper is only to console myself:

My head, my head.

Door, door.

Your hand, your hand.(Translated by Chana Bloch)

The first recipient of the prize named in his honor, Agi Mishol, has been praised for her sly wit, her ability to balance between the literal and poetic, to combine the everyday with the sublime. I will end with one of my favorite poems, an early work of hers:

“In the Supermarket”

Through the supermarket alleys I push a cart

As if I were the mother of two heads of cauliflower,

And navigate according to the verse-list

I improvised this morning over coffee.

Sale banners wave to shoppers

Studying the genre of labels on packaged foods

As Muzack entertains the frozen birds. And I too,

Whose life is made of life, stride down the dog-food aisle

Toward Mr. Flinker who confides in my ear that only the body

Crumbles but the spirit stays young forever, believe me.

Hurry folks, to the coriander,

Hurry hurry folks,

I’m the supermarket bard,

I’ll sing to the rustle of cornflakes,

The curve of the mutinous cucumbers,

Until the cash register will hand me

The final printed version

Of my poem.(Translated by Tsipi Keller)