Kaché Claytor is a PhD candidate in Hispanic studies in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and also earned a certificate in American Culture Studies. Having lived in Peru and Colombia, her research centers interdisciplinary approaches to how people of the African diaspora across Latin America respond to environmental catastrophe through activism, performance, and world-making.

Yo no me como ese pesca’o así sea del Chocó.

Ese pesca’o envenena’o, ese no lo como yo

Yo no me como ese pesca’o así sea del Chocó.

Ese pesca’o envenena’o, ese no lo como yo

Mucho ojo mi gente que quieren envenenarte la cabeza

con pesca’o malo en la mesa.

I don’t eat that fish if it’s from Chocó.

That fish is poisoned, I don’t eat that fish.

I don’t eat that fish if it’s from Chocó.

That fish is poisoned, I don’t eat that fish.

Be very careful my people,

they want to poison your head with bad fish on the table.

—ChocQuibTown, “Pescao envenenao” (2007)

This stark warning against consuming the essential food of the Colombian Pacific Coast was first issued by the Afro-Colombian music group ChocQuibTown in 2007. Deriving its name from a lexical fusion of the region, Chocó, and its capital, Quibdó, the group foregrounds its regional identity as it composes music filled with political messages highlighting the realities of coastal Black Colombians, including topics of environmental racism and degradation. Their lyrics — in rhythm with their melodic blend of traditional Afro-Colombian music, Hip-Hop, salsa, funk, ska and jazz — speak to Black Colombian identity, experiences and realities in the place they call home: Chocó.

Situated in the country’s southwest coastal region, the Pacific Coast is both rich in resources and home to the largest concentration of Black Colombians, which makes it vulnerable to exploitation. Despite being recognized for collective rights of ancestral lands, territories and natural resources according to Law 70 of 1993, which established collective rights for Black communities, Black Colombians are increasingly displaced from their territories, dispossessed of their land and subjected to toxic environments from illegal mining.

Illegal mining pollution contaminates rivers and fish with mercury and other metal waste, which can be absorbed through the skin via contact with tainted water and ingested by eating fish, a staple food in the region. In effect, inhabitants of the Pacific Coast have consumed lethal amounts of mercury. It has even been found in breast milk and in the womb during gestation. Mercury, along with other metal pollutants from illegal mining, can cause health problems, birth defects and death. This accumulation of noxious conditions led environmental activist, Goldman Environmental Prize winner and current Colombian vice president, Francia Márquez, to declare that “la contaminación de la minería es un genocidio” [the mining pollution is a genocide], years before she gained office in 2022.

In 2009, ChocQuibTown released the album Oro [Gold], which carried a throughline of highlighting ancestral gold mining and the environmental degradation caused by illegal mining in the region. In an interview with Esme McAvoy of Upside Down World, a news outlet devoted to covering social movements and politics in Latin America, lead singer Goyo explained that “my grandparents worked all their lives in mining, searching for gold,” which catalyzed the album’s name. Black Colombians have ancestrally mined gold not only for economic security but also as a practice that carries cultural significance. ChocQuibTown called their album Oro, Goyo continued, to “represent the value we put on our own music but also to take a critical stance against the irresponsible exploitation of gold in the Chocó. It contaminates the rivers and damages the area’s incredible biodiversity.”

As depicted in the lyrics above, ChocQuibTown’s 2007 hit single “Pescao envenenao” [Poisoned Fish], from their Oro album, discourages eating fish from Chocó. It is poisoned, they caution. The phrase “poisoned fish” has a dual meaning in Chocó, as it also critiques those who should be advocating for the land and its people. In the same interview with Upside Down World, Goyo explained: “We use poisoned fish as a metaphor to criticize the political discourse in Colombia. When we talk about fish in the Chocó, it’s understood as a symbol of abundance. The rivers are full of fish and it’s a staple food. When we talk of them being poisoned it’s a comment on the way corruption has contaminated all layers of the political system. The empty promises of so many politicians.” The lyrics carry multilayered significance to critique the corruption in politics along with the contamination of rivers and fish with mercury and other toxic metals from illegal mining. This song serves as a public service announcement, alerting communities not to eat the poisoned fish from Chocó. While the group released these songs and this album in the early 2000s, the soundtrack of violence, exploitation, contamination, poisoning and degradation continues into the present day.

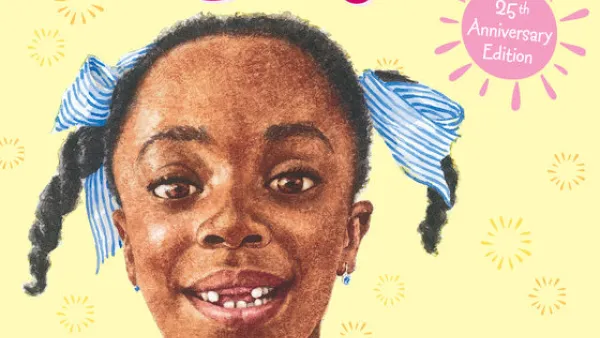

Headline image: ChocQuibTown performing in 2010. Photo via Flickr.