Interview with Faculty Fellow Allan Hazlett

If there’s one thing most people can agree on, it’s that it’s imperative to be your “authentic” self. This counsel is earnestly repeated to those seeking jobs, relationships, leadership roles, political office. Don’t be phony; be your true self. But it’s not so simple, says Allan Hazlett, a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities and an associate professor of philosophy. He pushes back on this conventional wisdom in his current book project, “The Wages of Authenticity.” Are there times when being inauthentic is a kindness? Are there times when being authentic is cruel? Below, Hazlett wades into the ethical dilemmas these questions provoke and much more.

Briefly, what is your book about?

The book is about the idea that you have to be authentic to be a good person. I define an “authentic” person as someone who is sincere and candid, but what this boils down to is that an authentic person is an honest person, a person who tells the truth and nothing but the truth. So the book is about the idea that all good people are authentic, in that sense. I give two arguments that this is a bad idea. The first one is that there are a bunch of ways in which it is good to be inauthentic and the second is that democratic politics goes badly when we treat authenticity as a requirement for political support.

What is the meaning of “authenticity” in your project? How is it different from the common usage — such as an “authentic ethnic food”?

I use “authenticity” to refer to sincerity, which is expressing only thoughts you have, and candor, which is expressing the thoughts you have (when it’s relevant). The inauthentic person, on this conception, is a poseur, someone who is fake or phony. The relationship between authenticity, in this sense, and other kinds of authenticity, or other things we use “authentic” to refer to, is interesting and not obvious. Inauthentic ethnic food isn’t “expressing thoughts that it doesn’t have,” whatever that might mean. But we do somehow think of it as being fake or phony.

What kinds of questions are you asking about authenticity in your book?

The central question is whether we should think that authenticity is required for being a good person. That leads me to consider questions about the various ways in which it might be good or bad to be inauthentic. And it also leads me to consider questions about what it’s like to value authenticity — what it’s like to think that authenticity is required for being a good person. I think there’s a particular kind of ethical framework, a way of thinking about what really matters, that comes along with thinking that all good people are authentic, that leads us to focus on authenticity at the expense of other things.

What sources are you consulting to help answer them?

In one part of the book, I need to compare my definition of “authenticity” with other ways of thinking about authenticity in philosophy, and for that I have been reading, and re-reading, some important historical texts, like Heidegger’s Being and Time. The whole project is inspired by a 2002 book by Bernard Williams, Truth and Truthfulness, so I keep coming back to that. It’s a really important book. If my book is a “poor man’s” version of Williams’ book, I’ll be happy.

“Authenticity” is generally understood as a prized characteristic, but you’re skeptical of that. Why?

There are two main arguments here. The first is that inauthenticity is sometimes a good thing. One of the examples I talk about in the book is discretion. Being discreet always, or at least usually, involves being inauthentic — it involves saying something you don’t believe or not saying something you do believe (even though it’s relevant).

The second argument is that thinking that authenticity is required for being a good person is bad for democratic politics. What happens when we think this is that we become so concerned with the possibility that politicians are saying something they don’t really think or not saying something they do really think that we ignore what they’re saying.

How might people see the drawbacks of authenticity in their own lives or the world around them?

I keep coming back to how we often hear people say that they don’t agree with what Donald Trump says, but they admire him for saying it. What they are admiring is Trump’s authenticity — they admire Trump for saying what he believes, even if it is rude, unpopular, extreme, norm-violating, “politically incorrect,” etc. Indeed, the fact that he says rude things is seen as evidence of his authenticity, by contrast with other politicians, who are seen as evasive and secretive. And I should say: the drawback here isn’t that the politics of authenticity is good for Trump, and therefore the politics of authenticity must be bad. It’s that the politics of authenticity leads us to ignore whether what politicians say is true or false, or right or wrong, and instead ask only whether they really believe it.

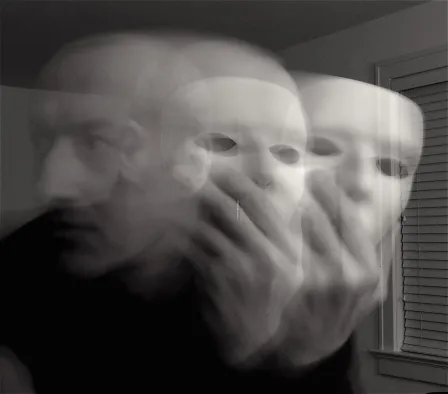

Headline image: Authenticity (2009), Necklace District, Detroit, Michigan, photo by Axel Drainville / Flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0.