Bailey Willden is a PhD student in Hispanic studies in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and is also pursuing a certificate in women, gender and sexuality studies. Her research interests include the intersections between race, sexuality and gender with notions of health and the body in contemporary Mexico and Mexican America.

“Is it possible to tell stories with figures and abstract forms? Can diagrams relate conflicts, meetings of minds or disagreements?” Those were the provocations that brought together genre-bending writer and visual artist Verónica Gerber Bicecci and a roomful of WashU and St. Louis community members to create a collaborative abstract comic, learning about the interface between image and idea along the way. Gerber Bicecci, who describes herself as “a visual artist who writes,” has exhibited her work internationally, and she has published several books, including Conjunto vacío, which was awarded the 3rd International Aura Estrada Literature Prize. Under Gerber Bicecci’s instruction, and buoyed by the nervous energy of excited novices, her book-making workshop was an inspiring and nourishing experience in at least three different ways.

Authentic interdisciplinarity

This workshop was an interdisciplinary experience. This academic buzzword is sometimes buzzed so frequently that the vibrations make it blurry, make it lose its clarity or meaning. It took an artist like Gerber Bicecci to bring such a diverse group of people into the same room and bring the esoteric word down to earth (earth being, in this case, room 142 of Olin Library).

Many of the challenges we face in actually doing interdisciplinary work are language problems. Each discipline speaks a different language, and the more hyper specific the lingo, the more a scholar is taken seriously in their own field while becoming increasingly unintelligible to everyone else. In the case of this workshop, we were dealing with dialectic crossed wires not only between disciplines but from the participants themselves. We were lucky to count in attendance several community members, including a vivacious bunch of high schoolers who sat with me in the back of the room (Gen Z slang is a linguistic anomaly of its own).

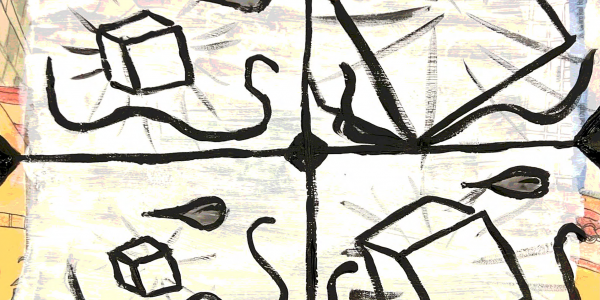

While we were invited to reflect on our own interests (academic or otherwise) as inspiration for our comic strips, Gerber Bicecci broke down language barriers in the workshop by reducing our complex web of signifiers down to three abstract characters. Our strips had to include a cube, a drop and a wave. We were given only a few sheets of paper and some black paint to bring these “characters” to life. Suddenly, this group made up of community members, humanists, social scientists and high schoolers was expressing itself in the same language and making a collaborative piece out of its seemingly disparate ideas. Rebecca Weingard, a PhD student of comparative literature, looked back on the experience, saying, “We were encouraged to reflect on our research interests and the relationship between them, and to use this as inspiration for our comic. I found this type of exercise to be productive and generative, and particularly loved the collective nature of the workshop, as we were all working with the same three characters on our individual comic and were therefore able to see how other participants approached the prompt in such different ways.”

Collaborative process

In my own work, I have constantly felt the pressure to be original, to come up with an insight or idea that did not exist before and get it out into the world with my name attached. So many of us hear this message: The work you accomplish on your own is the most valuable in the marketplace of ideas.

At another event during her visit, Gerber Bicecci discussed two of her published works, The Company and In the Eye of Bambi, both of which approach issues of originality. The Company is a rewriting of Amparo Dávila’s story “The Houseguest.” In the Eye of Bambi was directly inspired by the La Caixa collection of visual art from the White Chapel Museum. Many of her other works are similarly rewritten, reworked, composted or collaged. They pay respect to the great minds around her and achieve a level of communal sensitivity that easily gets lost in the wild goose chase for originality and intellectual property. Gerber Bicecci made this workshop an artistically democratic space as well. She provided tools, established a narrative foundation, gave brief instruction and overall created a communal space for ideas to flow freely. Then, she stepped back and let us create. Although the poster for the workshop has her name on it, the final product is signed by each and every one of the participants in our own handwriting.

Creative response

While I frequently approach the arts in my scholarship, I rarely have opportunities to get creative myself. The low stakes and the supportive and fun atmosphere of the workshop allowed me to access an artistic flow that I have seldom experienced before. I felt particularly inspired by the limited color palette and subject material available to us to create our comic strips. With only three forms and one color, I cut through a lot of the decision paralysis that often accompanies the start of a project and was able to complete a strip that I was proud of in less than two hours. What an achievement!

As I reflect on this workshop, I am determined to find ways to keep the spark of this experience alive. Even when I am writing papers or emails instead of holding a paintbrush, how can I access this artistic flow and feel inspired by what I do? In my research and my teaching, can I create an environment that is dynamic and democratic, where ideas can be freely exchanged without being impeded by hierarchy or competition? Can I see limitations as opportunities for creativity? Maybe we all need to find ways to break down barriers to communication and instead let our artistry and collaborative spirit color all that we do.

The Center for the Humanities was a co-sponsor of this event.

Headline image: A panel from Drop cube wave.