Interview with Faculty Fellow Colin Burnett

The James Bond franchise — populated since the 1950s by a multitude of high-profile TV shows, radio plays, comics, films, board and video games, and serialized newspaper stories — is a powerhouse production regime. Year after year, product line after product line, a constellation of licensed producers has released their own stand-alone content. In the process, says Colin Burnett, a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities and associate professor of film and media studies, they sparked a global 007 craze and modernized the practice of media franchising. He delves into this sophisticated storytelling and business strategy in his current book-in-progress, “Serial Bonds: How 007 Storytelling Modernized the Media Franchise.”

Briefly, what is your project about?

My project is about the art of storytelling in the James Bond franchise. Now, for some, that will sound rather odd as an area of focus. Sure, the Bond phenomenon is fascinating for how it reflects 20th and 21st century culture — the Cold War, the sexual liberation of the 1960s, the 1980s obsession with Grace Jones, George W. Bush’s War on Terror, etc. — but the franchise ultimately is of little interest as storytelling art.

Well, I challenge this assumption. Here’s what studying Bond storytelling reveals. That beginning in the 1950s, a new business practice, which we call media franchising, started to radically alter the art of popular storytelling across the globe. It did so by innovating new ways of telling stories that appealed to mass audiences — by spreading stories across multiple media at once.

One way became the Star Wars way — later adapted by the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Avatar and a few other properties. These franchises tell a single, unified story — they offer a single transmedia continuity to follow. But the Star Wars way has proven exceedingly rare. It demands a lot of resources.

Years before Star Wars, Bond innovated a different way, one now widely adopted in the industry, a “leaner” and more efficient cross-media approach I call threaded storytelling. Author Ian Fleming licensed partners in film, TV, comics and gaming to reinforce his Bond novels in marketplace. But writers didn’t create a single Bond continuity stretched out in all these forms. They produced a multitude of distinct continuities — a multitude of medium-specific “James Bonds” for consumers to follow. Fleming and crew were thus able to move serial fiction into the cross-media franchising age.

How would you describe James Bond, to someone who has never heard of the character? What traits are steady, and what has been variable?

I think most people believe the “classic” Bond to be a static figure, the Bond of the Sean Connery or Roger Moore movies — a Bond defined mostly by his actions. There isn’t much back story or depth there. In each adventure, he completes a short covert mission, returns to MI6, flirts with Miss Moneypenny (fig. 1), and receives new orders from his British intelligence boss, M. He stocks up on the latest high-tech gadgets from Q branch and sets off, traveling to exotic locales, taking pleasure in fine food and drink, and bedding several hyper-sexualized women along the way — three, to be exact. In the end, he thwarts a colorful scheme hatched by a megalomaniacal, often racialized villain bent on revenge, wealth or world domination.

This is the “formula” — of the movies. But the franchise presents us with many “James Bonds.” The original, Ian Fleming’s Bond, is a more rounded character. He develops, albeit ever so slightly. If the Connery and Moore Bonds are almost superhumanly unchanging and invulnerable to experience, Fleming’s is “going slowly to pieces” as the novels progress (fig. 2). His mind and body break down. Traumas pile up as he loses loved ones. The occupation of the spy increasingly robs him of his soul, of his ability to feel.

From films to comic books to video games, in the U.S. and abroad, from Ian Fleming’s first book in 1953 to today, why/how has the Bond franchise managed to cross so many different media, cultures and eras?

The answer is actually rather simple. Bond has circulated so widely, in so many forms and eras, because we are drawn to long-form storytelling, and Bond storytellers have exploited this expertly. We like stories that reliably hold our attention, not just from beat to beat or chapter to chapter within a single installment, but from installment to installment, and even from medium to medium. It’s as simple as that. We like the local narrative pleasures as well as those stretched out in time.

Now, not all franchises succeed in this. Bond has many appeals on its side. To be sure, its formula of sex, violence, globetrotting, and spy-driven fantasy and intrigue is part of what explains the franchise’s longevity. But plenty of fictional properties have used the very same attractions with much less success.

Ultimately, it is how this formula is used — in long-form stories, varied across media — that explains Bond’s widespread success.

What does this project add to the history of material and visual culture, and to the study of serialized storytelling?

That’s a great question. I would boil this project down to an insight into modern aesthetic sensibility. In our passion for serial stories, whether it’s Sherlock Holmes novels or the Fast and Furious movies, we relish the opportunity to discover shapes in time. This pleasure is not unlike listening to a piece of music or reading poetry, where patterns emerge as the minutes tick by, organizing our thoughts and sensations. Long-form popular stories like Bond rely on a different time scale, placing greater pressure on our attention and memory, and use narrative cues, not musical ones. But the effect — playing to our desire to perceive patterns across sequences of moments and forms — is fundamentally the same.

Art historian George Kubler says the following about the quasi-musical experience of history’s forms — that it entails contemplating “a variety of examples spread early and late in time, as well as high and low upon a scale of quality, in versions which are antetypes and derivations, originals and copies, transformations and variants.” The pleasure comes from an “intuitive sense of enlargement and completion in the presence of a shape in time.”

At the end of the day, I hope this project encourages others to study the distinct “shapes in time” that franchise narratives entice us with. I suspect that no two franchises are alike. And who knows. Perhaps once we’ve studied a critical mass of franchise stories, we may be able to trace their various forms down to some feature of modern psychology.

Do you have a favorite work in the Bond franchise?

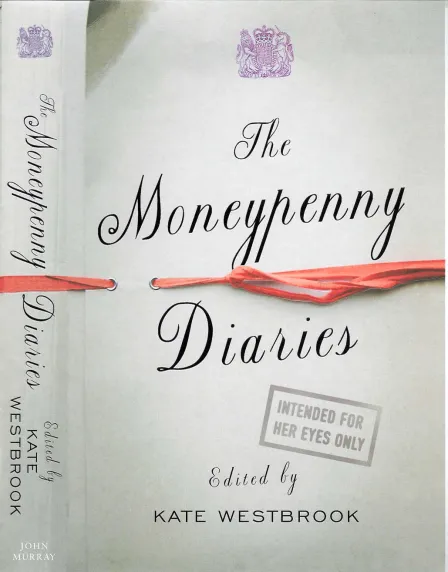

Part of what makes Bond so fascinating is the variability of the storyworld. Some writers even experiment with oppositional forms of storytelling within official franchise media. I would highly recommend Samantha Weinberg’s trilogy of novels, The Moneypenny Diaries (2005–08) (fig. 3), an alternate version of the Fleming continuity, one that feminizes it, re-telling events from the perspective of MI6’s iconic secretary. For anyone who thinks that Bond and Moneypenny never… Well, I shouldn’t spoil things!