Nathaniel B. Jones is an associate professor in the Department of Art History and Archaeology.

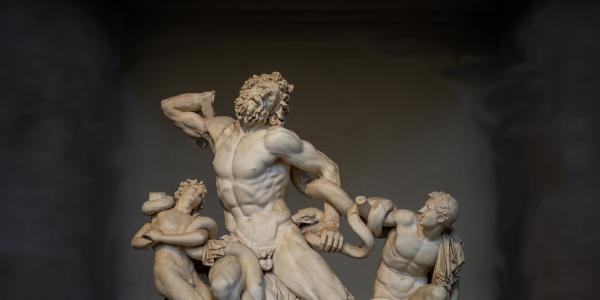

It is not the most famous or the most crowded corner of the Vatican Museums — that remains the Sistine Chapel — but even at 8:30 pm on a Friday, waves of tourist groups come up to an alcove in the Belvedere Courtyard. They are there to see the Laocoön (Figure 1, below), and as each new group arrives a pattern is repeated: the visitors crowd in, ducking around one another’s phones to find an unobstructed angle for a selfie and listening to a tour guide deliver, at least in the languages I can follow, a remarkably consistent and broadly accurate story.

The guides recount that this very statue was identified by Pliny the Elder, ancient encyclopedist and victim of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, as the product of three artists from Rhodes: Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athanodoros. That he, wrongly, claimed it was made from a single block of marble. That it depicts a scene from the deep mythological past, when a priest from the city of Troy, Laocoön, has warned the Trojans not to bring a large wooden horse inside the walls. But since the destruction of the city has been pre-ordained, and the Greek soldiers hiding inside that horse are destined to sack Troy, he, along with his two sons, is now being punished by the gods in the form of two poisonous sea snakes, who envelop and bite their writhing bodies. That the statue was re-discovered in January 1506 and immediately became a sensation, a treasured possession of the pope and source of inspiration for artists from the Renaissance on. That it represents the pinnacle of artistic achievement in the representation of human anatomy, motion and emotion, depicted at a single moment in time at the height of the story’s narrative drama, just before Laocoön’s anguished death cries were raised up to the stars, as Virgil puts it.

It is this last claim, enshrined in Gotthold Lessing’s 1766 text Laokoon, that has brought me to the Vatican this evening. It seems to me to depend in no small part on a modern European approach to media, and I am curious to see how it will hold up under first-hand scrutiny. Such an approach entails, firstly, a privileging of the expressive and narrative power of verbal text over material object or image, and, secondly, an internalization of the freeze-frame effect of mechanical reproductions of statues like this, first via the mechanism of print and later through photography. These media show the statue from a single point of view, almost inevitably the frontal one, which is immobile and immutable, and which, in the case of a photograph, records something like a single instant in time.

But this freeze-frame effect is not, I find, much in evidence during the embodied experience of viewing the statue. That experience is one of the iterative opening and closing of different points of view over an extended temporal duration. As I move around the alcove housing the statue, the instantaneity of Lessing’s version of the statue is distended, and a single, fixed narrative dissolves into a variety of possibilities.

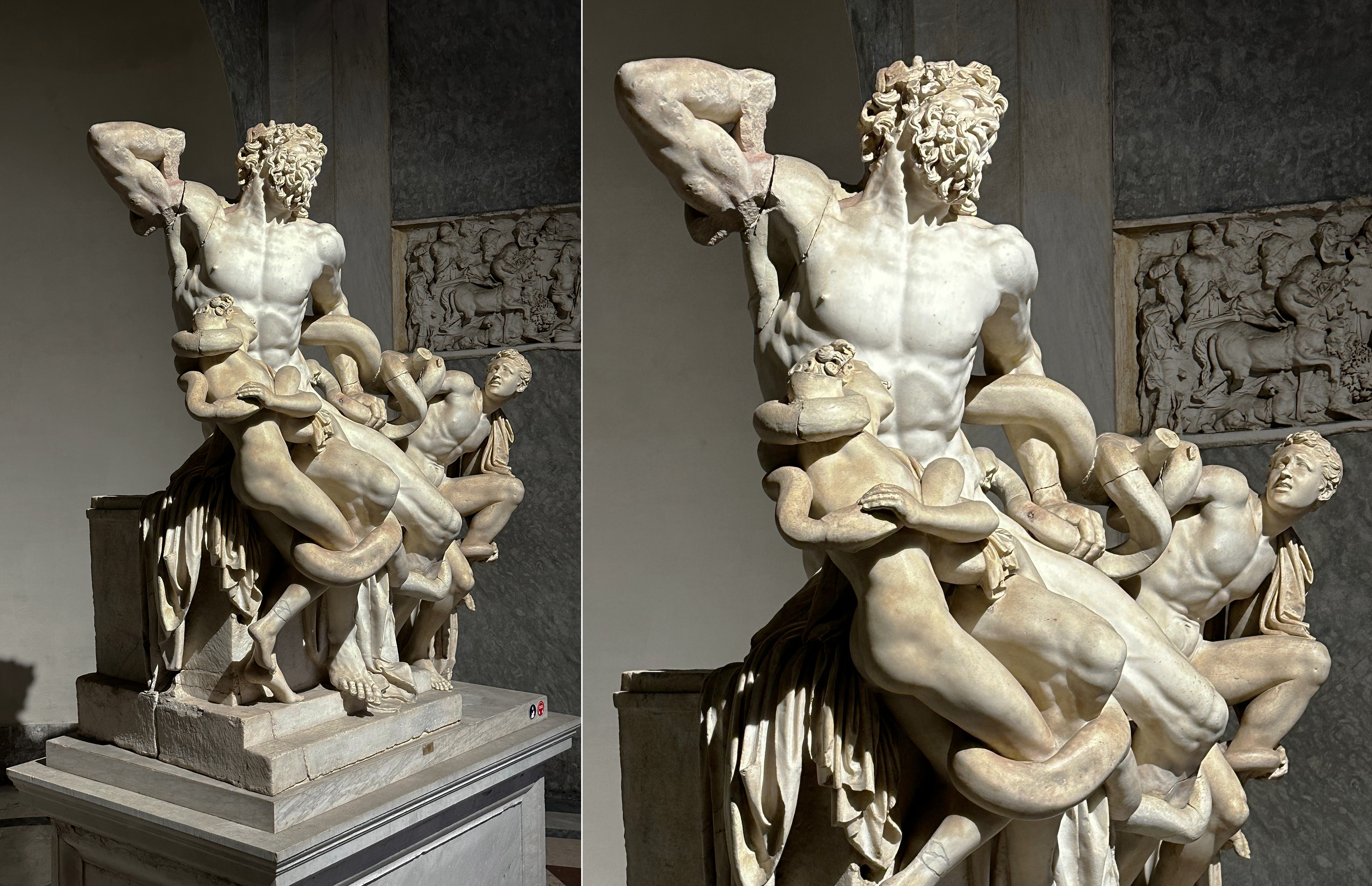

In approaching the group from the right (Figure 2), for example, the integrity of the bodies of the figures practically disappears, but the faces of Laocoön and his younger son achieve renewed prominence, and the head of the older son, seen entirely from behind, becomes a stand-in for our own act of viewing, albeit from within the very myth. The nature of the action, from this view, recedes into the background, and the composition becomes about intensity of emotion.

From the left (Figure 3), by contrast, action and reaction take center stage, as bodies are not only more legible in their entireties, but narrative time stretched out. Since we cannot make out the face of the younger son, his limp form seems to be already without life, and the gesture of the older son, pulling a snake down and off his left ankle, offers hope for escape. Each point of view seems to lead in a potentially different narrative direction, in ways that are much less linear than the textual accounts of either the mythical event or the statue itself.

Such instability tends to be squeezed out by the traditional tools of scholarly analysis, aided by the technologies that mediate and disseminate our images and ideas about the past, but it is fundamental to the supposedly naive experience of the tourist. And it points to a broader set of possibilities.

Each point of view seems to lead in a potentially different narrative direction, in ways that are much less linear than the textual accounts of either the mythical event or the statue itself.

By re-centering the embodied encounter with works of ancient art — the Laocoön and others — we might revivify such objects, liberating them not only from textual sources but from the fixed, immobile viewpoint of print and photo and opening up a new set of perspectives to understand how ancient artists sought to create stories in stone.

Headline image: Laocoön and His Sons by Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athanodoros of Rhodes, 40–30 BC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.