Interview with Faculty Fellow Fannie Bialek

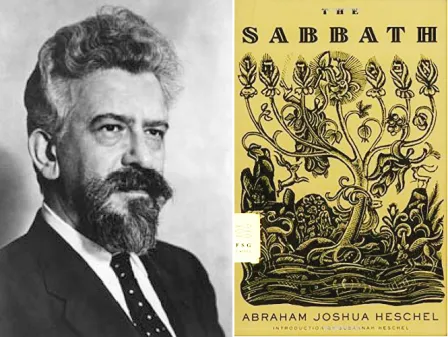

In 1951, rabbi and Jewish intellectual Abraham Joshua Heschel published a slim volume on the observance of the Sabbath, a weekly withdrawal from workaday concerns in favor of time spent in spiritual communion. It was written amid concern among Jewish leaders about rapidly suburbanizing American Jews drifting from traditional Jewish practices, including by driving to synagogue on Sabbath or not observing the Sabbath at all.

“It’s easy to imagine Heschel was asked to write a few hundred words to distribute as a pamphlet or read from the pulpit,” says Fannie Bialek, assistant professor in the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics and a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. “Instead, he wrote one of the most beautiful religious texts of the 20th century, richly poetic and filled with beautiful imagery,” Bialek says. A classic of Jewish spirituality since its publication, it is beloved by millions of readers.

Almost 75 years later, Bialek is taking a fresh view of The Sabbath, revisiting it not as work of religious instruction or mysticism but as a source of radical political imagination resonant with struggles against racial injustice, income inequality and climate change today. “Heschel writes about the divine imagination revealed in the gift of Sabbath, through which human beings should imagine a realm other than the realm of finite space,” Bialek says. “There is profound critical potential in that idea, for concrete political questions.” Below, we preview her work-in-progress, “Rereading Sabbath: Aspiration, Urgency, and Critique in Heschel’s Time and Ours.”

Briefly, what is your book about?

The book is about how what Heschel calls “the aspirations of time” can reframe contemporary political thinking about vulnerability, injustice and motivation for change.

Heschel argues that the Jewish Sabbath is a realm of time, distinct from the realm of space, where we live the other six days of the week. In the realm of space our aspirations are competitive: You and I can never occupy precisely the same space, so our projects in the realm of space are defined by jostling for possession, security and control. But time can be spent together — we can share time, fully, in a way we can never fully share space. That defines the aspirations of time differently: not to have, but to be; not to own, but to give; not to control, but to share; not to subdue, but to be in accord, as Heschel writes.

I interpret this description of the different aspirations of time and space as a powerful political challenge, based in the iterative practice of Sabbath. As it arrives each week to disrupt ordinary life, Sabbath interrupts the aims of our competitive lives with the possibilities of time spent together. I think we can read this interruption as a call for critique, asking and allowing us to question our lives in the other six days by the light of Sabbath time. What we see, I argue, is that forms of injustice that seem intractable or irremediable by the rules of competitive space may be better approached as injustices of time. We also see that a significant challenge of ethics and politics is the sustaining of urgency to address injustices and needs for change over time — a question of motivation that resonates particularly with the fight against climate change.

Can you start us off with a quick primer on Heschel?

Yes! Heschel was a prominent rabbi and Jewish public intellectual in the mid-20th century. In addition to a profound influence on American Jewish life, he was deeply involved in the civil rights movement, including participating in the march from Selma to Montgomery. His numerous books, articles and popular writings were and are read widely by American Jews and, especially in his lifetime, well beyond the Jewish community. He was a public religious leader of a kind less often seen today, but somewhat similar to Thomas Merton, the Niebuhrs, and even King himself: a prominent moral voice, heard widely, speaking to a more religious American public than we know in the 21st century, and often pushing for the status quo to move left — though primarily with religiously informed moral arguments, not because of any party allegiances.

Heschel’s life followed a defining historical period in which many Jews moved from Eastern Europe to the United States. Born in Warsaw in 1907 to a prominent family of Hasidic rabbis, he pursued a rigorous yeshiva education as a young person and then a philosophical education in Germany as a young adult. He managed to leave Eastern Europe as the war began, arriving in New York in 1940. After a brief time at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, the main seminary of American Reform Judaism, he taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary on the Upper West Side of Manhattan from 1946 until his death in 1972. He was a leader of a generation that was the last to know the old world of Eastern European Judaism before the Holocaust, and then to make a life in the United States in the postwar period.

What is important to understand about the concept of time in Heschel’s book Sabbath?

The Jewish Sabbath arrives each week to interrupt life, whether you’re ready or not. “Suddenly, it was time,” as Susannah Heschel, A.J. Heschel’s daughter and a scholar of religion at Dartmouth, describes of their family’s observance in her preface to The Sabbath. “Whatever hadn’t been finished in the kitchen was suddenly left behind as we lit the candles and blessed the arrival of the Sabbath.”

In Jewish practice, Sabbath is observed joyfully, with celebratory meals, singing and an emphasis on spending time in community with others: in synagogue, hosting visitors and at festive tables. Traditional observance of Sabbath includes not working, driving, writing or handling money, but these prohibitions, Heschel explains, are not deprivations like a fast. They are merely the implications of what doesn’t matter on Sabbath, because Sabbath is a gift of time.

Sabbath, for Heschel, is a “cathedral in time,” a divine gift of time set apart from the other six days of the week. Its time is spent together, sharing in its goods without competition or attempts to control. It is also filled with aspirations for what our time together might be, made urgent by each Saturday’s waning light. Sabbath time thus recasts the competitive aspirations of life in the other six days as smaller than they might appear in their moment and easily unjust, ready to turn the urgency of finitude into a mere contest with the people standing near you. But we must not let our “acquisition of things in space” overtake our “aspirations in the realm of time,” Heschel writes; time is the holier realm, though one easily abandoned by the attitudes and ambitions we learn in our competitive realm of space and things.

It is all too easy to let space overtake our “aspirations in the realm of time,” he argues, because the modes of engagement are different in the two realms; the goals are different and the attitudes we develop through them different as well.

These goals, Heschel suggests, aren’t all bad: They allow reasonable relations in the realm of space that should not be abandoned but pursued justly for much of our lives, for the “six days” of every week that belong to space. The problem is not that we engage in the realm of space and its ambitions of possession and control, but that our engagement in the realm of space encourages us to ignore and abandon the realm of time, which teaches us much more, and has much more potential.

Traditional observance of Sabbath includes not working, driving, writing or handling money, but these prohibitions, Heschel explains, are not deprivations like a fast. They are merely the implications of what doesn’t matter on Sabbath, because Sabbath is a gift of time.

During your fellowship, you’re writing about this view of time in relationship to modern-day political problems of the “stolen aspiration” and “disproportionate vulnerability” of Black Americans. How does the focus on time (versus material things) add to your understanding of these injustices?

The modern “justice system” and legal framework of nation-states encourages us to think of justice in terms of possession and control: I want what is due to me, which is defined by space, things and money. People’s time is used in lieu of money or things: If you can’t pay bail or fines, you will be imprisoned, but your time is then “valued” in what Heschel would describe as spatial terms, governed by the competitive rules of the realm of space.

Yet many of us have the intuition, and understanding, that our time can’t be merely “valuable” in this way, whether in our understanding of what our time is “worth” in a job or, more significantly, in the understanding that imprisoning someone for days or years because they can’t make bail isn’t just, or that slavery is a theft of more than some monetary amount of lost wages.

In one of my favorite lines of the book, Heschel writes, “The danger begins when in gaining power in the realm of space we forfeit all aspirations in the realm of time” — when in trying to acquire space we fail to spend our time well, and fail to understand what “well” might mean. For Heschel, what it means to spend time well can only be understood from the realm of time, not from the realm of space. When we apply the logics of space to time — even in the figure of speech I’m using here, to “spend” time well — we miss time’s grandeur, which lies in its lack of limitation and competition. Viewed from the realm of space, time is something we should spend and, even better, steal to acquire more space and things. Viewed from the realm of time, space and things are hardly so significant, and certainly not significant enough to justify the theft of time from ourselves and others that seems so quickly appealing in the realm of space.

A prophetic call to respond to thefts of time as well as space, and to attend to ongoing injustice as an added dimension of injustice and not just a greater or lesser quantity of it, is what has animated many recent revivals of discussions of reparations as a response to the structural injustices perpetrated against Black Americans. Similarly, the movement for Black lives, against police violence, has often called on ideas of injustice in disproportionate vulnerability, and the larger effects on what life is like lived in fear of state violence. Some of these injustices are thefts of aspiration: The domination or destruction of a person’s ability to aspire, or the effort to dominate others in this way, as I argue was perpetrated by the enslavers of Africans and their descendants in the United States. Understanding the injustice of enslavement in terms of the attempt to steal aspiration and not only labor suggests that repair must be sought for more than material thefts. Others are injustices of disproportionate vulnerability: the unjust distribution of vulnerability — the possibility of what could happen in time to come — that accompanies the injustice and horror of violence perpetrated on members of persecuted groups. I argue that Black Americans’ vulnerability to police violence is its own injustice in this way, in addition to perpetrated incidents of violence, and that movements against police violence must attend to disproportionate vulnerabilities to it, as well.

Headline image by Jacky Watt via Unsplash