Jey Sushil is a Graduate Student Fellow in the Center for the Humanities and a PhD student in the Department of Comparative Literature and Thought, Track for International Writers. His research interests include postcolonial studies and world literature.

This is not about me.

This is about an elephant.

I walk with an elephant that no one can see.

An elephant lives in my head.

I carry him on my shoulders, on my back.

I wear an elephant on my sleeves, on my shirt.

The elephant is not invisible.

It is just brown.

It is in the room.

Can you see it?

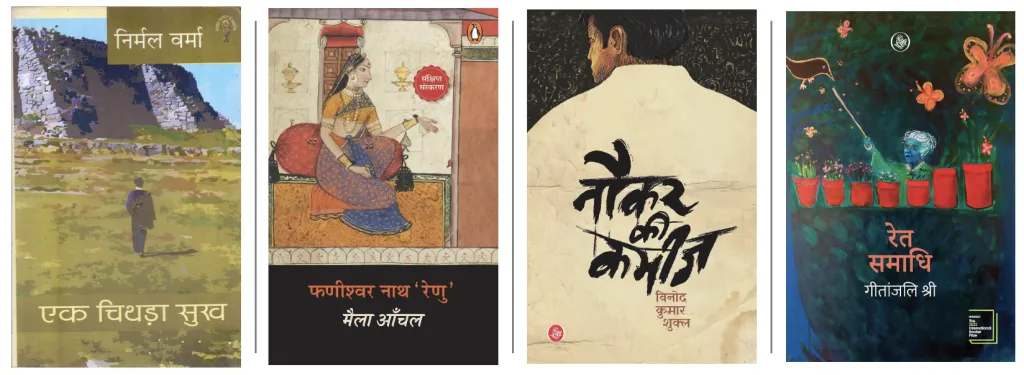

When I started my PhD program in comparative literature at WashU as a student from a small mining town in eastern India, it was difficult for me to locate myself in the classroom. The world literature that I was studying with my fellow students embraced, among other writers, familiar Indian authors such as Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, Raja Rao, Kiran Desai and Vikram Seth. These authors wrote in English and are well known in Western academia. They are part of the canon, a canon that is Anglophone in nature and tilted toward one language. But they are a small part of Indian literature. As a researcher, I had different authors in mind. I tried to bring up the rich traditions of writers from India’s massive geographical language regions: Hindi (from the north), Malayalam (southwest), Bangla (east) and Oriya (southeast), for example. But language barriers naturally limited our discussion to books that were available in English.

To my surprise, I learned that translations (into English) from other languages represent just 3% of the total U.S. book market (as documented since 2008 by the website Three Percent at the University of Rochester). This is a logical explanation for the fact that people in the U.S. do not have much knowledge about Indian literature except for Rushdie and Arundhati, New York Times best-sellers and the most well-known authors from India. In this English-dominant world, I began to slowly make sense of Indian literature in translation. Because of the vastness of Indian languages, it felt like an elephant: a majestic animal significant to Indian mythology (Lord Ganesha, said to have written the epic Mahabharata, is an elephant-headed God), a symbol of India’s slow-paced economy and, so the parable goes, difficult for blind men to fathom.

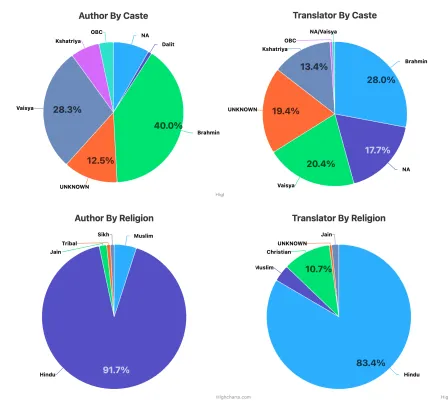

The elephant that I now call modern Indian literature has become my obsession. I have embarked on a journey of introducing it to my fellow students and teachers, with the goal of eventually reaching all who speak, write and understand English. It’s an enormous task: There are 22 officially recognized languages in India and even more that are not yet recognized by its constitution. I had to begin somewhere, so I started with Hindi novels in English translation for the simple reason that Hindi is spoken and understood by more than 47% of the population of India. Spoken and understood — not read. India by nature is a multilingual country where the majority of the population understands more than one language.

If some Indian writers are already writing in English, one might ask, why is there a need to read works translated from Indian languages? The answer lies in a revealing statistic: Only 9% of the Indian population can read or understand English. Members of this group largely live in big cities, are upper class and upper caste and come from elite backgrounds. Few outside of this category have been able, like me, to work in English during their higher education years. Simply put, most literature written for Indian readers is not in English.

Languages carry cultural, linguistic and aesthetic traditions all their own. The world of English and the world of Hindi or any other language in India is different, distinct and has literary insights to offer. Even in translation, those aesthetic and narrative styles can enhance our understanding of India and its literature. I believe that reading Indian literature in translation will give us a more nuanced picture of the country and its people.

In recent months, I have directed my obsession toward building a website, India Translated, that will serve as an archive of Hindi novels in English translation since 1947. But this is just the beginning. My intention is to expand the archive to different languages and genres of Indian literature so that it can represent the spectrum of Indian literature for any English reader. The latent hope of this project is to showcase the elephant in its totality.

The elephant I am carrying on my shoulders is now shared through the website, and it is up to the readers of the literature to take a ride and decide for themselves. In one of the great Hindi novels, A Window Lived in the Wall, the protagonist, a lecturer named Raghuvar Prasad, is waiting for public transportation to his college when he sees a mahout (driver) atop an elephant. An urge comes to him to ride the elephant, and in few minutes the mahout comes near him, gets down and asks him if he wants to ride the elephant. (I’m not going to reveal whether he accepts the ride or not. Read Vinod Kumar Shukla’s novel, translated by Satti Khanna, to find out what happens!) I see myself as the mahout of that elephant, asking my readers: Would you like to ride the elephant?

Headline image by Chandan Mahanta