Interview with Faculty Fellow Lori Watson

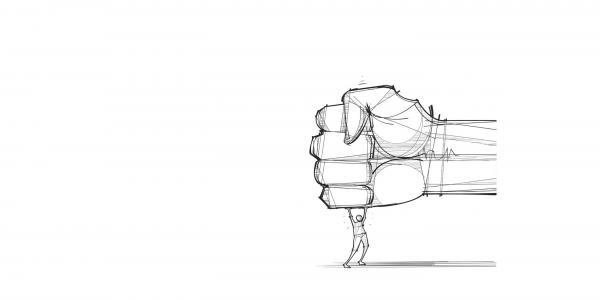

“Philosophical work that addresses inequality of status, power and standing of historically disadvantaged groups too often tends to be siloed as ‘merely’ feminist philosophy, race critical philosophy, philosophy of disability, and so on,” says Lori Watson, professor of philosophy and a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. With her current book project, “On Domination,” Watson instead argues that theorizing from the specific position and experience of the historically subordinated is essential to constructing a general theory of domination. Drawing on the work of gender theorists, critical race theorists and colonial studies — as well as empirical work documenting and situating the intersections of inequality experienced by women, people of color and colonized populations — she aims to break new ground in how to think about domination and subordination relations. Below, she gives an early look at her work-in-progress.

Tell us about the book you’re writing.

The book is about the concept of domination, which has been central to many political philosophers’/theorists’ analyses of power relations among human beings.

Some forms of power dynamics among humans are unjust and oppressive. Understanding what domination is, how it occurs and is perpetuated is important for identifying specific forms of power dynamics in which some persons benefit at the expense of others. This is especially apparent among persons as members of groups (class, race, gender, etc.) and so the book aims to offer an argument as to what constitutes domination/subordination relations as well as when such relations are oppressive.

The hope is that the project can add clarity to a specific form of injustice, so that we can formulate appropriate collective responses to ameliorate oppression that flows from domination.

How has the concept of domination been understood in contemporary political philosophy? How have feminist thinkers critiqued this theory?

A short answer to this question is very difficult! Our colleague Frank Lovett [Political Science] has an excellent book that maps out various conceptions of domination while defending his own view of domination in the republican tradition — as when some persons have the capacity to enforce their arbitrary wills upon others.

There is much to be said in favor of this conception; however, my view is that it is too narrow. Domination, as a form of power, extends beyond the will of those in the power position. In other words, domination isn’t solely about the power some have to enforce their wills upon others; it also consists of the power, more diffuse, to construct the terms of social cooperation and the social identities of those who are subordinated.

Feminist thinkers haven’t so far engaged too directly with republican conceptions of domination. Instead, they have often aimed to give an account of a specific form of domination — male domination — and as such don’t have a general theory of domination. Moreover, in my view, they often conflate oppression and domination. Part of the aim of by book is to show the distinctness of each concept, but also to show how they are related. The line I am pursuing is that domination/subordination describes a structural relationship of asymmetrical status hierarchies, not all of which are necessarily wrong or unjust. The concept of oppression explains the ways in which some status hierarchies are harmful and unjust.

Your book will begin with a description of the experiences of subordinated persons. Why is it important to start there?

Starting from the experience of those subjected to (unjust) forms of power is, I think, necessary for understanding how systems of domination work as well as their breadth. Aiming to understand and examine the ways in which oppressed persons (persons harmed by domination/subordination relations) experience power exercised over them, how they understand the forms of inequality they are subjected to, and how they see their status diminished relative to those with power is really ground zero for anyone who approaches these issues from a feminist perspective. While feminism is not monolithic, there are deeply shared methodological commitments for feminist analyses, including, importantly, that our analyses are accountable to the lived experience of those we theorize.

Human beings have evolved to compare, sort and then rank much of what they encounter. You can see from an evolutionary perspective why doing so would be advantageous: We want to know which food is better; which food will kill us; which animals are useful (good), dangerous (bad) or indifferent (neutral); who is friend and who is foe, which climates are better and so on. ... But our social practices of ranking and sorting far outstrips any functional purpose.

Your book will elaborate the personal responsibilities for members of dominant groups. What are those responsibilities?

I am not far enough along in the project to have a worked-out answer to this question, but I can say something about my approach and the ways in which this question arises in light of my work.

One conclusion I have drawn from my various research is that human beings are a status-seeking species. What I mean by that is human beings have evolved to compare, sort and then rank much of what they encounter. You can see from an evolutionary perspective why doing so would be advantageous: We want to know which food is better; which food will kill us; which animals are useful (good), dangerous (bad) or indifferent (neutral); who is friend and who is foe, which climates are better and so on. So, our brains are primed to categorize and rank (superior/inferior).

But our social practices of ranking and sorting far outstrips any functional purpose — think of the numbers of top ten lists generated daily on the internet, think of the innumerable “debates” about which kind of music is better or more valuable, think of the (social) value we attach to very expensive items that have no use value, etc.

And so, I aim to approach the question of responsibility in terms of correcting our projection of status onto persons as member of groups in light of the fact that humans inevitably (though contingently) project status evaluations onto virtually everything. So, how do we illuminate the ways in which we engage in such imposition of status and how do we shift or channel that trait away from harmful imposition of status upon humans? The ultimate answer will require change beyond any individual and yet individuals must, too, change and reorient.

Headline photo by Jackson David on Unsplash