Mark Beirn is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History and a Graduate Student Fellow in the Center for the Humanities.

What began as a simple question, “Why do cities have airports?” developed into a multi-sited investigation of the relationship between infrastructure and empire in urban spaces over the long 20th century. As a PhD candidate in Washington University’s Department of History, I follow the infrastructural turn in urban studies to investigate how airports formed new international borders that segregated and limited movement based on categories of difference shaped what Harsa Walia and others call “border imperialism” in Berlin, Istanbul, and Nairobi after the First and Second World Wars.

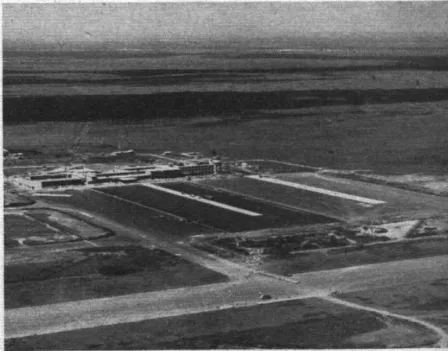

Nairobi’s Embakasi International Airport opened in 1958 with great fanfare at the height of British decolonization, quickly becoming a hub for commerce and communications in East Africa and an asset for the emerging nation-state of Kenya. Annual reports from Embakasi’s first years of operation reveal that the volume of passengers, freight, and livestock passing through its terminal, warehouses, and runway far exceeded planners’ initial forecasts. This new border infrastructure transformed Nairobi into a “port city,” bringing with it a new set of international laws regulating trade, communications, and public health in ways that mirrored older colonial governance of segregation and economic extraction. Critical to Embakasi’s financial health was its capacity to serve as a transit airport, an official International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) designation, which drew lucrative long-haul flights carrying passengers (generally white Europeans traveling between Europe and Australia or South Africa) to Embakasi for refueling.

Increased air travel coincided with a renewed post-WWII global concern with endemic disease like malaria and yellow fever. Despite the Nairobi’s advanced airport infrastructure and optimal weather conditions, Kenya’s classification as a yellow fever endemic zone (along with other sites in Africa and Latin America) by the World Health Organization (WHO) created new challenges and opportunities.

While Europeans transiting through Nairobi were not required to be vaccinated against the yellow fever, they were expected to remain in the airport during layovers as long as 12 hours to avoid contracting the disease. Many disobeyed these orders, either out of boredom or curiosity, leaving the airport grounds to seek out entertainment in the city. In response, Kenya’s Directorate for Civil Aviation (DCA) implemented stricter quarantine measures and requisitioned public areas in the terminal building to create separate transit lounges to hold these antsy passengers. Here, a traveler’s origin and destination linked with their ethnicity and nationality to become a determinant factor in regulating movement.

The demarcation of the airport grounds as a “yellow-fever-free zone” contradicted white settler narratives of colonial Nairobi as a modern sanitary city and undermined colonial control over the movement of Africans. Measures undertaken by the DCA to maintain the airport as a quarantine zone required a significant local labor force. This opened up new opportunities for Africans whose own movement within Nairobi was monitored and curtailed by decades of violent colonial policies.

Because transit flights often landed at night when airport staffing was minimal, initially making it easy for unauthorized passengers to skirt customs and go into the central city, airport authorities staffed up the night shift. Africans worked the transit lounge, while credentialed “night nurses” staffed medical facilities to treat air sickness and other travel-related ailments well after the daytime doctors had gone home. Samuel Kemoni joined a team of “searchers and oilers,” to scour the capacious airfield for mosquitos and larvae in oxidation ponds that handled the sewerage, in shallow pools of water in hoof prints, divots in uneven soil, latrine buckets, and other potential breeding grounds. By 1961 Embakasi had become a 24/7 operation in a nation preparing for independence.

Understanding state and individual responses to yellow fever at the dawn of the jet age may be instructive as individuals and governments seek to understand the spread of disease that has spread rapidly around the world in the age of COVID-19. Just as scholars have sought knowledge from the Influenza Pandemics of 1918 and 1889, Nairobi’s response to neo-colonial classification of yellow fever provides insight into the randomness of the spread of disease that travels old imperial routes so easily with hosts by plane and car, not just train, subway, and steamship.

As Black feminist writer and PhD candidate at UC San Francisco Zoé Samudzi recently tweeted in response to news reports on the rates of COVID-19 cases in African countries, “How are we meant to have responsible discourses about international pandemic without considering the politics and infrastructures that allow particular people to travel the world more freely and with less institutional restriction than others?” Indeed, understanding the ways in which global infrastructures impede mobility in ways that continue practices of empire is vital to understanding how viruses spread unevenly across the borders of empire at a new scale created by international aviation that connects the global and the local.

Headline image: Airport Nairobi NBO, SAS DC-6B, Bernt Viking LN-LMT at Nairobi Airport, Kenya. 1950s. Courtesy SAS Museum, Norway.