Interview with Faculty Fellow René Esparza

Residential segregation based on racial and economic inequality is a pre-existing condition that exacerbates any transmissible health threat – from tuberculosis to COVID-19 to AIDS, the latter of which Faculty Fellow René Esparza is taking up in his new book project, “From Vice to Nice: Race, Sex, and the Gentrification of AIDS.” Weaving methodologies from medicine, geography and history to construct a case study in Minnesota’s Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Esparza, an assistant professor in the Department of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies, exposes the enabling conditions of injustice and impoverishment that continue to catalyze ill health and disease — as well as collective remedies against them. Below, he gives us a preview of his book in progress.

Briefly, what is your book about?

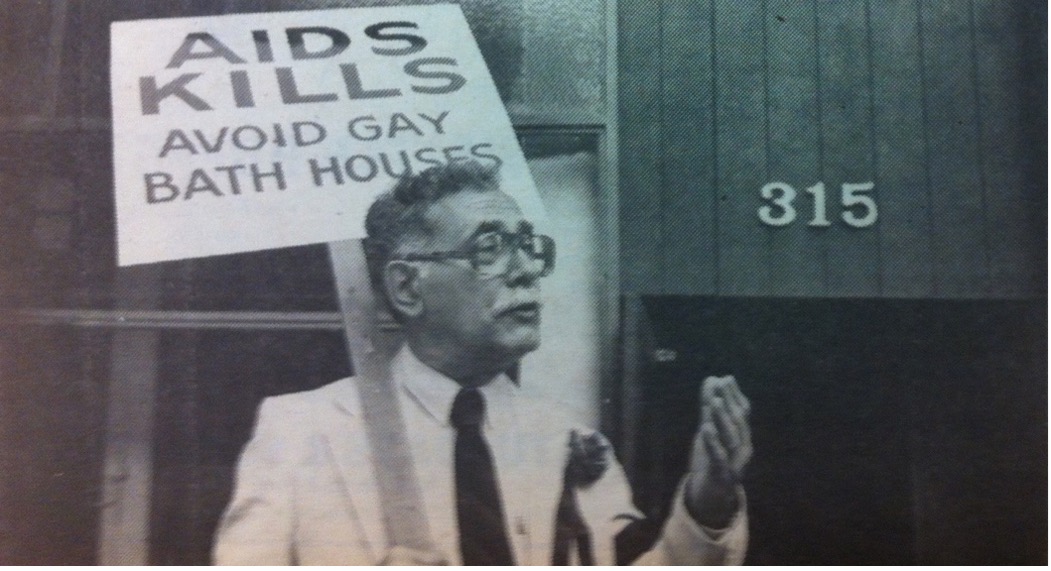

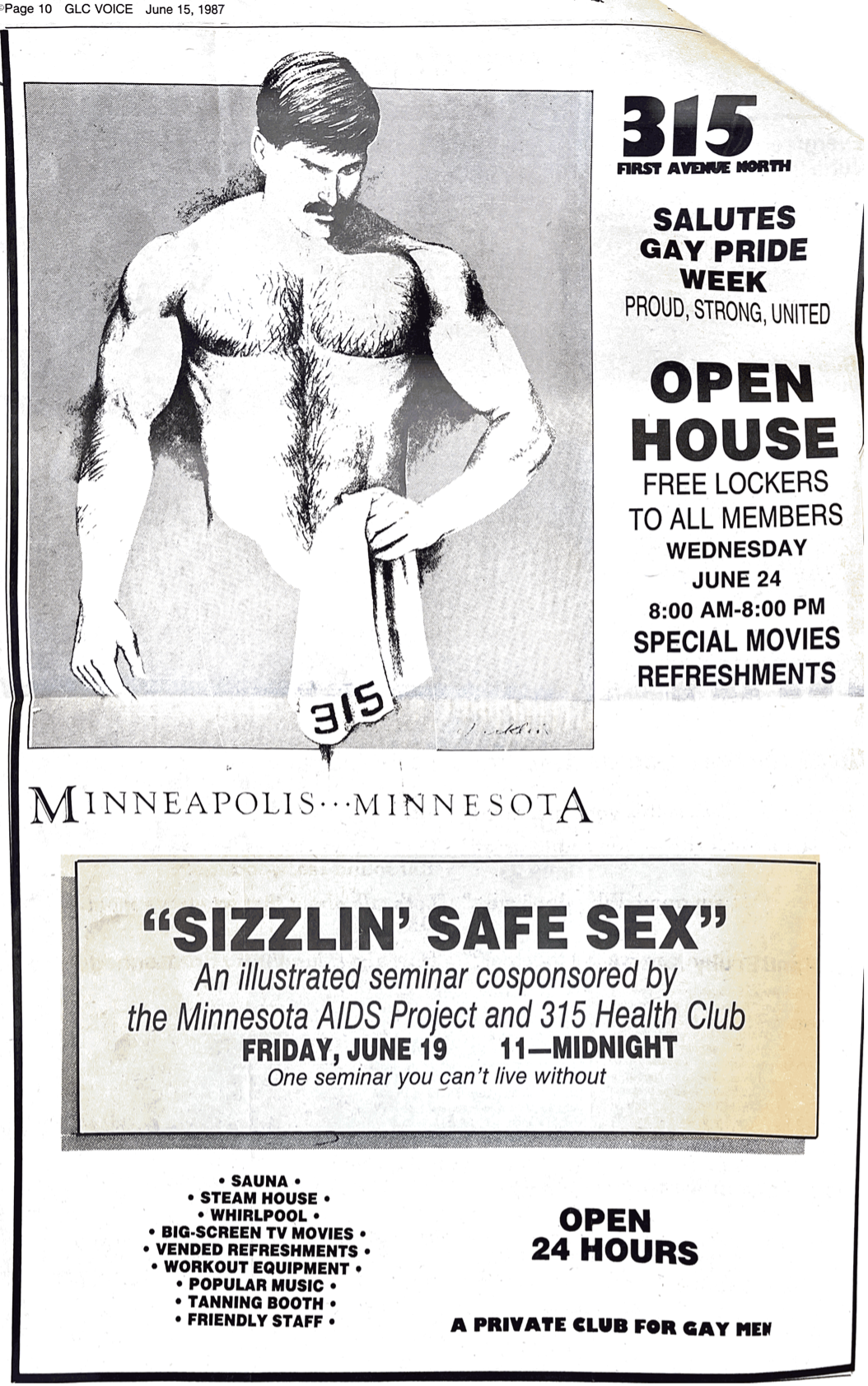

“From Vice to Nice” rethinks the history of the U.S. AIDS epidemic in relation to the gentrification of central cities and its attendant system of residential segregation. It focuses on the spatial determinants of health to insist that the driving force behind the racial disparities of the U.S. AIDS epidemic have not been the deviant behaviors of LGBT people or people of color but rather the unequal living conditions in which these populations have been historically confined, conditions that become embodied as ill health and vulnerability to disease.

I argue that real estate is crucial to understanding the story of the U.S. AIDS epidemic — on the one hand, how some LGBT leaders mobilized the private housing market as a protective shield against HIV, but only for those whose intimate relations upheld the monogamous, couple-centered household; on the other hand, how residential segregation created a welcoming set of socio-biological conditions for HIV to feely disperse among immunosuppressed communities.

In a climate of structured impoverishment and compromised health, a viral infection like HIV found (and continues to find with COVID-19) the perfect host in racially segregated and economically divested neighborhoods. Through a case study of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul that widens our primarily bicoastal and metropolitan understanding of the U.S. AIDS epidemic, I uncover how access to the private housing market for certain gay men came to provide immunological safeguards at the expense of racialized others. These home-based LGBT responses to AIDS, I show, operated in the service of private development, helping to physically distance and, thus, spatially inoculate some gay men — those with racial and class mobility — from the racialized ecologies of urban abandonment through which the virus traveled.

Tell us about the “risk behaviors” theory the epidemic. What factors were emphasized, and what did that mean for people with HIV/AIDS?

Although AIDS may no longer make as many news headlines as it once did, HIV continues to infect tens of thousands of Americans each year, disproportionately impacting communities of color. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2019, 36,801 people received an HIV diagnosis in the United States and its dependent areas.

The racial disparities that existed in the early days of the virus have persisted 40 years into the pandemic. In 2019, Black/African American people accounted for 42 percent of all new HIV diagnoses although only accounting for 13 percent of the U.S. population.

One could easily assume that the demographic profile of the U.S. AIDS epidemic is due to specific practices of sex and drug abuse — that is, “risk behaviors.” Research, however, shows that not to be the case. Black men who have sex with other men (MSM) have comparable or even lower rates of unprotected anal intercourse than MSM of other races or ethnicities. They report fewer sex partners than white MSM. They are also less likely to report substance use or engage in commercial sex work. Studies do show that Black men are less likely to know they are HIV positive and are also less likely to report taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), which decreases viral load. HIV-positive people who do not take ART are more likely to transmit HIV to sex partners during unprotected sex.

Instead of “risk behaviors,” epidemiologists are now focusing on “sexual networks” to explain the racial disparities in HIV infection. Black MSM are more likely to participate in networks of sexual partners that include Black men already living with HIV. The higher viral load in smaller — and, I would add, more segregated — sexual networks compounded with other social determinants — poverty, homelessness, unemployment, mass incarceration, lack of education and inadequate access to healthcare — all contribute to the disparate risk for HIV infection among Black men.

How is racial segregation central to the story of the epidemic?

The history of America’s urban “ghettos” serves as the prehistory of the U.S. AIDS epidemic. Health geographers have shown that “disease diffusion,” or the movement of disease through space and time, is determined by the organization and stratification of a society. The AIDS epidemic adhered to the basic patterns of “hierarchical diffusion,” a pattern of disease transmission in which diseases jump from city to city (generally from larger cities to smaller ones) before spreading out from cities to surrounding communities. Given the dispersion of HIV through the nation’s urban hierarchy, the epidemic must be understood in relation to suburbanization and simultaneous ghettoization after World War II.

Due to the racism but also homophobia that pervaded postwar housing benefits, people of color and LGBT people were systematically excluded from white heterosexual suburbia. The Black and Latinx ghettos that grew in prominence in central cities existed alongside and overlapped at multiple scales with emerging “ghettos” of marginalized white gay men and lesbians. (Though queer people of color straddled both communities, we know racism — both structural and interpersonal — and economic interdependence with families of origin excluded them from gay ghettos.) This postwar ghettoization of people of color and LGBT people resulted in a pattern of geographic concentration and social interaction that would sustain the U.S. AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. Thus, the economic and social isolation established through residential segregation — not individual or communal “high risk” behaviors per se — ensured that the primary drivers of the epidemic would likewise be the racialized poor and gay and bisexual men.

In 1996, when the U.S. Federal Food and Drug Administration [approved?] antiretroviral therapy, AIDS went from a death sentence to a chronic, but manageable, condition — for those with access to the new medications. With HIV-positive gay men living longer, many turned their attention to same-sex marriage. Sociologists have shown that changes in sexual attitudes translate to changes in sexual geographies, engendering a “post-gay” era. Acceptance and assimilation, the primary features of this post-gay era, opened previously off-limits residential districts to gay men, especially those with the racial and class mobility. But the same has not been true for other populations that were also historically confined to certain neighborhoods.

In short, urban ghettos of poverty and sexual marginalization were crucial to the emergence and structuring of the national AIDS epidemic at large. And continue to contextualize ongoing disparities.

This book is situated within a growing body of work related to “spatial” determinants of health. What new knowledge is gained with this analysis?

My focus on the spatial determinants of health builds on what medical sociologists call “embodying race,” a concept that shifts our attention away from biomedical and behavioral explanations of ill health toward the structuring of “collective embodied vulnerability” within urban ecologies of racism. I meld this geographical analysis of health with a queer and feminist theoretical framework to show that the ghettoization of racialized poverty and sexual marginalization — not individual “risk behaviors” — provided (and continue to provide) the context for the arrival and distribution of HIV into a full-fledged national crisis.

As research has documented, residents of racially segregated and economically impoverished neighborhoods are more likely to experience increased malnutrition, concurrent infection, low birth weight, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, environmental poisoning, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections and substance abuse.

Not surprisingly, COVID-19 also struck some of the neighborhoods hardest hit by HIV/AIDS as both viruses travel by exploiting the spatial stratification of American society. (Black and Latinx people tend to live in poor segregated neighborhoods without access to sound medical care, and they are more likely to live in cramped, multigenerational homes where social distancing has proven nearly impossible.) An engagement with the spatial determinants of health, thus, attunes to us how people’s place in space is a major contributing factor in their health and quality of life. But it also underscores the insidious history of residential segregation in the United States and reminds us of the importance of material remedies to offset these lethal legacies.

Headline image by Rafael De Nadai via Unsplash