Shirl Yang is a Mellon Modeling Interdisciplinary Inquiry Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. As a literary theorist, she researches writers and artists who ask whether it is possible to take on the market as a site of political reimagination.

4 pm, Tuesday, February 25

Keynote lecture: Cannibal Capitalism: The View from Trump’s America

Nancy Fraser traces the roots of our current crisis and looks to Marxism, feminism, anti-racism/anti-imperialism and ecological and democratic theory for ideas on how to come together to effect an emancipatory transformation of society.

RELATED EVENT

Panel discussion: Are We Toast? Humanities Under Capitalism

12 pm, Wednesday, February 26, 2025

Free and all are welcome! In-person and online viewing options.

When teaching Silvia Federici’s monumental essay “Wages Against Housework,” I like to ask my students what they think “against” is doing in the title. I ask because I have needed that reminder myself: The first few times I tried to describe the essay, I found myself referring to it as “Wages For Housework,” second-wave feminist campaign that Federici was a part of.

A prepositional awareness is crucial to understanding the essay’s intervention. The naturalness of “wages for” is precisely what makes “wages against” in Federici’s title so striking. If one take on the exploitation of women performing unwaged labor might be content with extending the wage form, Federici’s non-idiomatic use of “against” explodes paradigms of assimilation to point to something else. “Against” gives linguistic form to an appeal that is not an appeal at all. In this case, form realizes content: The essay’s defamiliarization of what should count as labor, and what the political consequences of that defamiliarization would be, works at level of language as well. This is all to say that how we write theory goes a long way in introducing conceptual problems in ways that activate readers’ intuitions about them, and something as simple as a preposition can be instrumental in that project.

The importance of prepositions and how theory is written came to mind again as I was reading Nancy Fraser’s Cannibal Capitalism. I was struck by a particularly memorable line in which Fraser responds to Marx’s famous passage on the “hidden abode of production.” In an oft-cited section in Capital, Marx explains the social relation through which labor-power comes to be bought and sold as a commodity through the metaphor of a back office. In Cannibal Capitalism, Fraser frames her own project as one of following Marx “behind” to this “hidden abode of production,” only to peer “behind” that at what is “more hidden still.” The doubling of “behind,” like Federici’s counterintuitive use of “against” that tripped me up years ago, signals that something is being insisted on in the theorist’s positioning their work. In this game of relay, Fraser builds on Marx’s spatial metaphor to introduce another dimension to his conceit.

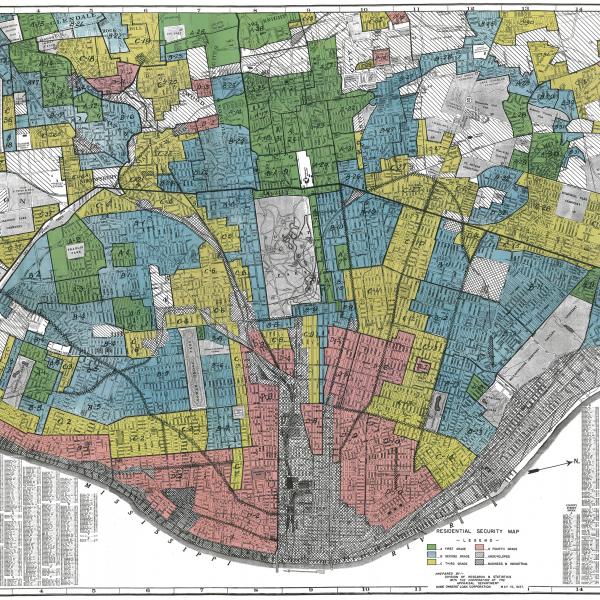

What does it mean to look behind the (already hidden) relations of exchange to examine realms that are “more hidden still”? In Fraser’s case, it means looking at to the conditions of possibility that must be in place for production to even happen. It means, in other words, building an “expanded” conception of capitalism. This more integrated view rethinks distinctions between free and unfree labor, production and reproduction, nature and society by asking how these distinctions are produced — legally, culturally, politically — and how they change. In a chapter on the shifting boundary between social reproduction and “properly” productive activity, for instance, Fraser shows how the site most associated with care work — the family — went from being a focal point for middle class reformers concerned about destabilized gender roles in industrializing Europe, to the ideal recipient for the “family wage” in postwar America that saw the state assuming limited and provisional responsibility for the reproduction of white households, to a social formation contending with a care work system that had been “dualized” under neoliberalism — commodified for those who can afford to outsource, privatized for those who cannot.

An expanded view of capitalism also allows us to spot solutions to capitalism’s “cannibalism” that circle back to the market, answers like a lean-in feminism in which social hierarchies are preserved, if stretched, slightly, or a “progressive” neoliberalism in which a politics of recognition becomes cover for reproducing class divisions. The question of what alternatives could look like is an ongoing one in Fraser’s work more generally, and no less in this book. I was intrigued by her brief meditation on the role markets might play: Markets in a socialist system, Fraser muses, should not be used at the “top,” for the distribution of social surplus, or at the “bottom” to address basic needs, though they might play a role “in-between.” (What this would look like in practice is left open, however.)

Cannibal Capitalism can be read alongside work by scholars such as Silvia Federici, Tithi Bhattacharya, Lucí Cavallero and Verónica Gago, Robin D.G. Kelley, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Jackie Wang, Mike Davis and Justin Akers Chacón, Neferti Tadiar (and more!). These thinkers put forward the kind of expanded view of capitalism Fraser espouses, one that necessarily incorporates discussions of dynamics that, at first glance, fall outside of the economic. Such work and its elucidation of the inextricability of the economic from the political and cultural worlds it is embedded in makes anti-capitalist critique a rich area of study and struggle.