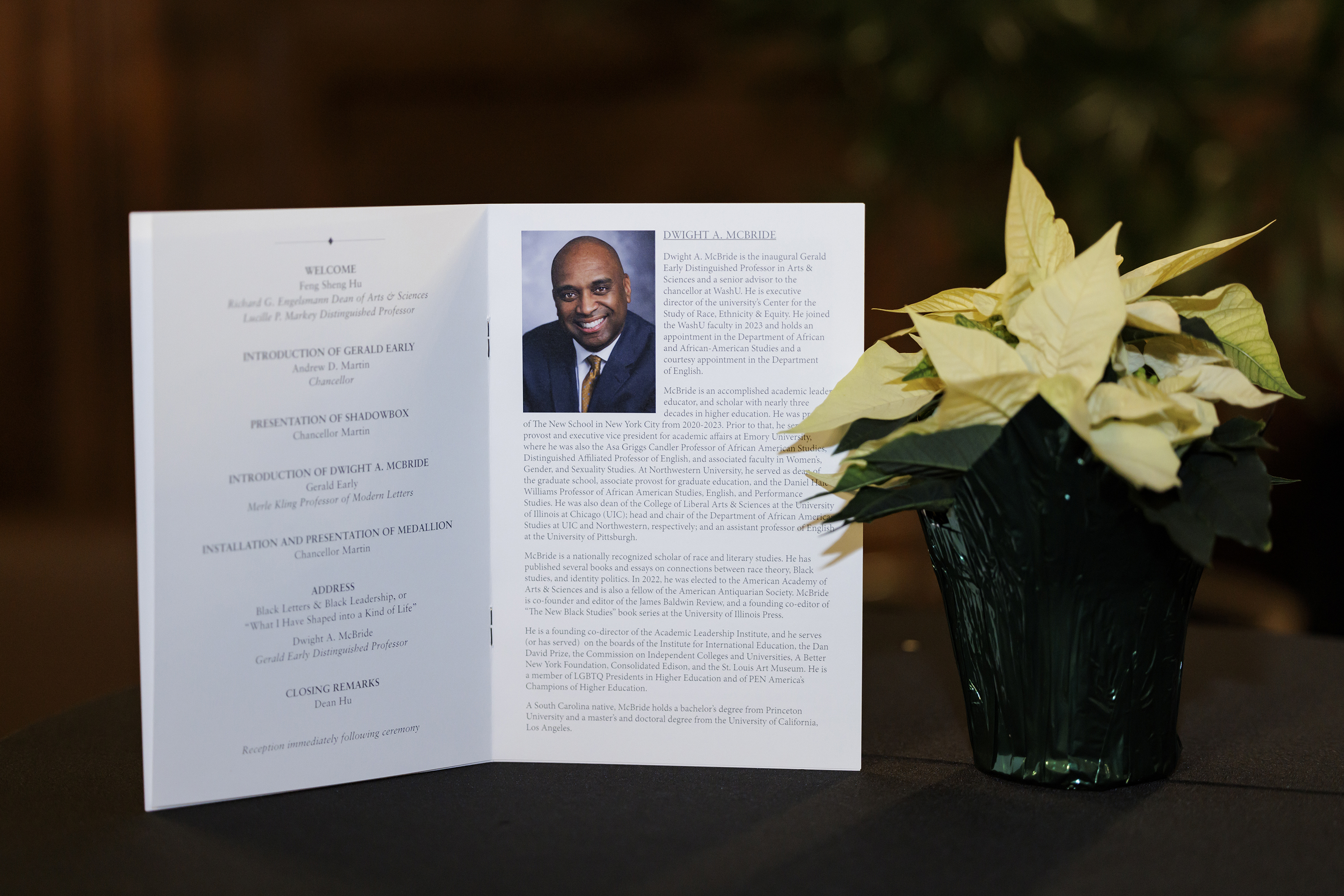

Dwight A. McBride, a leading scholar of race and literary studies, was installed as the Gerald Early Distinguished Professor of African & African American Studies at Washington University during a ceremony in December 2024. He generously agreed to allow republishing of his remarks here.

I am both humbled and deeply grateful to be honored as the inaugural Gerald E. Early Distinguished Professor of African and African American Studies. It is especially meaningful to be installed in a professorship bearing the name of my beloved colleague Dr. Gerald Early. Gerald stands as a peer among the most distinguished scholars, writers, educators, and leaders in American letters. His intellectual contributions have profoundly shaped the understanding of African American culture, history, and literature. As a professor at WashU—where he also held numerous academic leadership roles—he has inspired generations of students and colleagues alike. Gerald’s writings have earned him widespread recognition, and his leadership in both the academic and public spheres continues to elevate the discourse on race and culture, making his a vital voice in American scholarship. I commit to doing my best to live up to the example set by the namesake of this incredible honor.

Part I: Shaping a Life

I begin with a poem by Lucille Clifton as an epigraph to frame my thoughts:

won’t you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

I was not destined to become an academic. Indeed, I am quite certain that growing up as I did—son of a sharecropper’s daughter and a manual laborer’s son in the small town of Belton, South Carolina—I had neither met any such people, nor understood it as a career to which I might even aspire. But I was fortunate that even as textile workers in rural South Carolina, my parents knew well the significance of a college education. And though they themselves never had the opportunity to attend college, they worked tirelessly to make certain my younger sister and I both did. To this day I remain inspired by their example of uncommon sacrifice.

Their example is, in part, the reason I so deeply appreciate the importance of providing access to that same opportunity to all members of our society. And given the shifting demographic trends in the U.S. (and notwithstanding the fear this strikes in the hearts of many of our fellow citizens), it is more important now than ever that we be mindful of issues of access to higher education. I am a true believer in the power of higher education, quite literally, to change lives. I am living proof of that. Indeed, perhaps, the closest I have come in my own life to anything that resembles a kind of religious fervor is my belief in higher education; not only as an engine for social mobility, but also as a critical institution for advancing an educated citizenry, which is indispensable to sustaining a functioning democracy. There was a time—and not so long ago—where even the U.S. government shared the goal of educating more of its citizens. We now seem to be moving into an era where our government appears hell-bent on destabilizing, or worse dismantling, the sector. That political shift is significant and deserves our ongoing vigilance.

Now undoubtedly, my vision and values have been shaped by my own experiences as a native son of South Carolina; an undergraduate at Princeton; a graduate student at UCLA; an instructor at Santa Monica Community College in my final two years of grad school; as a visiting instructor at Occidental College; as a dissertation fellow at Louisiana State University; and as a faculty member and leader at institutions including the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Illinois at Chicago, Northwestern University, Emory University, The New School, and now WashU. I remain proud of the formal and informal education I received in each of these contexts. I am humbled by the many mentors along the way who—long before I held any title—affirmed what native ability and talent I may have had, and who nurtured it to become more than it would have been left to my own modest circumstances. So as much as we celebrate individual achievement in the academy, I remain keenly aware of the investments of the many who have contributed to any success and recognition I’ve enjoyed in my career.

While, on one level, a facile reading of my resume portrays an academic life that has involved successive scholarly achievements and a well-worn route through progressive leadership roles, that would only be part of the story. To be clear, the “politics of racial respectability,” as a dominant strategy of resistance against white supremacy, plays its part in encouraging such a reading of my professional life. Indeed, this is among its shortcomings as a strategy against anti-blackness. Narratively, the politics of racial respectability often conceals just as much as it reveals.

It conceals the fact that while I was, indeed, the first African American in nearly all of the leadership roles I entered, I was also the first openly gay person in these roles as well, which was never included as a part of the press release. It conceals the fact that while my academic pedigree is an enviable one, it was also enabled by affirmative action, which had little to do with my abilities or aptitude but, rather, was necessary because of the racial prejudices that had ossified in our institutions over decades of our nation’s racist history and the exclusion of people of color. It conceals the myriad ways and times when I (and others like me) bite our tongues and keep our heads down in order to, as the saying goes, “go along to get along.” It conceals the fact that in nearly every encounter I have had with white colleagues—which have in nearly every context been the majority of my interlocutors (fellow faculty, fellow university leaders, board members, alumni, parents, donors)—in any social or professional situation, I am aware that I am always thinking first of how best to make them comfortable in my presence before ever considering my own needs. I think of the time, all the wasted time and energy these concealments have consumed over the course of my life, and I wonder at what more I (and others like me) might have achieved unburdened by such time-consuming and emotionally depleting labors. And for a fleeting moment, I can glimpse something of the unearned grace of the comfort and ease of the experience of what it must feel like to be a similarly situated white man in a white supremacist world. I hesitate, though, to even call it an “experience” since the genius of whiteness is that its subjects never really have to confront the relative privilege of their positionality in our world because it is so naturalized. All of a sudden, and from this perspective, the “lightness of being” doesn’t seem quite as “unbearable.”

Part II: Celebrating Black Excellence

Black genius, Black excellence, Black achievement, and even Black joy, then, all exist despite a society intentionally designed to dismiss them at best, and actively to thwart them at worst. So, for me, every instance of these is cause for celebration. And so we return to Clifton’s poem “won’t you celebrate with me,” which is at once, a poetic act of resistance and affirmation, one that asserts the value of Black life against the dehumanizing forces of systemic oppression. In this work, Clifton positions celebration as a radical act that challenges the erasure of Black subjectivity and the violence of oppressive structures like the “Babylon” she invokes. To celebrate, in Clifton’s parlance, is not merely to survive; to celebrate is to claim agency and to refuse the negation of Black life that history and society have so often imposed.

The reference to Babylon carries with it a historical and symbolic gravity that cannot be overlooked. In biblical traditions, Babylon is the epitome of imperial oppression and spiritual corruption—a site of domination where identities are stripped away and autonomy denied. Clifton’s invocation of Babylon places her in a lineage of those who have endured and resisted systems of violence and dehumanization. For Clifton, Babylon is not merely a metaphor for historical injustice; it is a living, breathing force embedded in the structures of racism, sexism, and systemic inequity.

For Clifton, celebration is not merely an emotional response, but is also a deliberate political stance. In the face of Babylon, Clifton does not lament or acquiesce. Instead, she celebrates. The poem’s opening line—“won’t you celebrate with me”—is not a request but a summons, a call to bear witness to the miraculousness of her survival and self-creation. Clifton’s declaration, “what did i see to be except myself? / i made it up,” underscores the centrality of self-creation. This process of “making up” oneself is borne not out of whimsy but instead of necessity—a necessity forged in the crucible of Babylon’s oppression. In refusing to allow Babylon to define her, Clifton claims the power of authorship over her own identity. Her reference to “this bridge between / starshine and clay” suggests a liminal space, a tension between the earthly and the transcendent, between the material realities of suffering and the spiritual aspirations of joy and freedom. This “bridge” is where Clifton lives and makes a way to thrive. She exists in defiance of Babylon—not as a product of its destruction but as a creator of something entirely new.

Clifton’s emphasis on shaping a life points to a fundamental distinction: the difference between a life that must be consciously constructed against oppression, and a life that unfolds with the unearned privileges of inheritance and security. Those whose lives are not dictated by systemic violence can imagine life as unimpeded, as the natural unfolding of potential. Their lives, in this sense, are modeled by a culture that affirms their value, offers structures of support, and provides a roadmap for existence. Clifton’s life, by contrast, is “a kind of life” because it cannot rely on those structures. It must be shaped within a world that seeks to deny its very possibility. By acknowledging the absence of a model, Clifton calls attention to the systemic conditions that render Black lives precarious, yet her act of shaping a life becomes an assertion of agency challenging those very conditions.

Part III: Reconciling Theory & Justice

I remember the first time I realized that even the very critical methods of my stock and trade in academic discourse were implicated in the ideology of white supremacy. It was the first year of my PhD program at UCLA in a literary theory course, where I had written a seminar paper (based on the theoretical writings of Paul de Man) titled “Race as Allegory.” My professor had encouraged me to work on developing the paper into a journal article for publication. Indeed, it would, just two short years later in 1993 after much revision, become my very first scholarly publication, appearing in Modern Fiction Studies under the title “Speaking the Unspeakable: On Toni Morrison, African American Intellectuals, and the Uses of Essentialist Rhetoric.” If the story ended here—being published in the fall of my 3rd year of graduate school—it would appear that it was a tale of academic success. However, and once again, that doesn’t tell the entirety of the story.

You see, when I completed that seminar paper, the process of its writing nearly shook my faith in the entire academic humanist project. As it happened, that fateful winter quarter of 1991 coincided with the brutal beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, which had been videotaped and broadcast for all the world to witness. As a young Black man, I had certainly even by then already had my own unpleasant and impertinent “run-ins” with law enforcement, though none that rivaled anything like King’s. For so many of us, the existence of the videotape of Rodney King’s beating—horrifying as it was—was vindication. It was proof that everyone could see for themselves of the violence (not to mention the more garden-variety profiling and disrespect) perpetrated on Black bodies at the hands of law enforcement. At the time, many of us hoped this just might turn the tide and excite the moral outrage of our fellow citizens such that real and lasting change might be possible. A little over a year later, however, we all know how that turned out. All four of the LAPD officers on trial were acquitted and an urban uprising erupted in LA.

Against this political backdrop, the writing of a finely tuned analysis of the concept of race, in a discourse that demanded all the passion and personal harm be written out in place of dispassionate analysis and argument, and in a theoretical lingua franca that limited its audience to scholars and intellectuals, felt hollow and ineffectual at best. Was this offering up of Black racial suffering to be dispassionately examined and analyzed by those who did not have to encounter the effects of the hurt, violence, and injury that Black people lived the best critical discourse could produce? Is this what I aspired to do for the rest of my professional life? Write papers for audiences of hundreds, at best, in hopes that others would cite them in the production of yet more such papers? If that was my labor, what was I doing to liberate Black people and to further the cause of social justice? This soul-searching—which I would come to understand is not an uncommon phenomenon for Black scholars—would send me into a crisis of faith in the academy for the next couple of years.

I completed my second year of graduate school, filed for the MA (for which I had at that time met the degree requirements), and promptly took a leave of absence for one year, during which time I worked full-time as the Interim Assistant Director of the Academic Advancement Program (AAP) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). AAP was, at that time, the largest affirmative action program in the nation, and was aimed at furthering the achievements of underrepresented students at UCLA. AAP offered tutoring across the undergraduate curriculum, and was home to an academic counseling unit that served the needs of those same students. The Director of AAP—at the time one of the most visible people of color on campus—had offered me the job, as he had been one of the people I had turned to for advice about my growing crisis of faith in the life of the mind.

Looking back, it was a job for which I had no real experience except that I was smart, a quick learner, extremely well-organized, and deeply committed to the values and goals of the program. I supervised the counseling unit of about a dozen academic advisors, oversaw the day-to-day administrative operations of AAP, and helped organize the annual summer bridge program for entering first-year AAP students (a program that I myself had taught in for the first time just the prior summer). This was my first foray into leadership, and into doing work that (at the time) felt more practically and directly linked to social justice. Supporting programs that were instruments of the success of students of color was exhilarating. It also didn’t hurt that I was earning a salary that outpaced anything I had known in my life up to that point, which was not unimportant to this working-class, first-generation kid. Every day I could see how my efforts, my interventions, were making a difference. Although I didn’t fully appreciate it then, this was likely when I first became seduced by the potential of work in academic leadership.

It is not an exaggeration to say that my academic career was rescued by legal scholar and theorist, Patricia Williams. A fellow graduate student, who was a couple of years ahead of me in the PhD program and in whom I had also confided regarding my doubts about the academy, had recommended her book, The Alchemy of Race and Rights: Diary of a Law Professor. Reading Williams was a watershed moment in my career. It was the first time I had witnessed a mind at work that was committed to high theory, but in a way that did not exorcise Black experience, or evacuate it of all its pain and passion. Indeed, the book itself stood as testament that one not only could marry the two, but that for theory to be useful or relevant in addressing Black life (in an anti-Black society and its institutions), one, indeed, must find ways of merging the two. Williams did not write out the passion, the anger, the rage—all, by the way, profoundly human responses to the social and literal violence done to Black people in an anti-Black world. She embraced and used it; and wrote in a way that was suited not only for academic audiences, but in ways that might also speak to broader reading publics.

A couple of months before my year as Interim Assistant Director concluded, I was called to a meeting by the Dean of Undergraduate Programs. He noted that the Director of AAP and I made a good team, which we did. The Director was a big ideas and vision guy, who was great at the podium and inspiring. And I was good at taking those ideas and turning them into actionable plans and programs and keeping us on schedule and on budget, which the Dean appreciated. He inquired about my plans and asked if I might be interested staying on in the role. Honestly, I hadn’t considered that as an option. I had taken the job knowing this would be for one year. During that time, I was also pursuing a singing career on the side—I had done demo work for a rising songwriter, worked in background vocals in some recording sessions, recorded a demo of my own, and was performing regularly. Since I hadn’t made plans beyond taking that job for the year, the conversation with the Dean really called the question for me.

I thought about my life as a singer. And while I certainly had a talent, I had also met and worked with some amazing vocalist who were even more talented than I, who would never “make it” in the way we conceive of successful careers in the music industry. This was the era, after all, of Madonna and the boy band during which “video killed the radio star.” Real vocal talent was not the recipe for success, rather it was about the selling and packaging of “a look” and a brand. I remember thinking that if the likes of Luther Vandross and Aretha Franklin were just being discovered in this time, they would likely never have become the household names they are because they didn’t have the right “look” to be packaged and mass produced in the age of MTV. So I ruled out music as a career path because it seemed too arbitrary and precarious for me as another Black man with a voice, not to mention the liability of being gay.

By comparison, graduate school and a life in research, scholarship, and teaching, was also something I was good at. And I knew that if I applied myself and continued to excel that I had a much better chance of carving out a path to success. After all, at that time, the academic job market had not quite yet devolved into the “job lottery” that it is today for newly minted PhDs. What’s more, at this time jobs in African American literature and culture were on the rise as English departments were catching up to the scholarly and curricular changes demanded by the diversifying of the old white male-dominated idea of the literary canon. By the time I finished my PhD, the turn-of-the-century culture wars were in full swing. The first edition of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature (the highly anticipated and much-discussed canon-building project at the time) would be published in 1996, the year I defended my dissertation. I felt that I had an opportunity to control more of my own destiny as an academic. And even in 1993 I knew enough to know that if I wanted to return to a career in academic leadership, having the PhD was going to provide more options in that world too. So, the pragmatic considerations won out in the end, and I circled back a few days later to thank the Dean and to let him know that I had decided to return to my PhD program that fall.

This was not the last time I would have a crisis of faith in the academy. After all, institutions that were not designed with you (or others like you) in mind are destined to fall short in their accommodation of you. As I have often said, especially to fellow Black scholars, other scholars of color, and women scholars I have mentored, you cannot hold out for any institution to love you. Institutions aren’t constituted for that. Love, at its best, is particular and bespoke; institutions work at generalized and “ready-to-wear” scale to serve their constituents. And the idea of the generalized subject upon which they function all too often re-inscribes the hegemony of whiteness.

My institutional life, then, was born out of this context and has been ever committed to making space. Making space for inclusive excellence. Making space for often misunderstood scholars doing work at the intersections of disciplinary norms. Making space for the building of academic community that can help sustain those who do not always feel at home or welcomed in our institutions. Making space for the broadening of our ideas of what leadership should, and can, look like and be. Making space so that in the creation of our policies and processes we are attuned to how these help or hinder those who persist and thrive at the margins of our institutions.

I close with the words of my beloved late mentor and one of the world’s literary treasures, Toni Morrison, words that have sustained me and been a touchstone of sorts for me in every leadership role I’ve held, and have guided the way in which I endeavor to conduct the life of the mind to which my career has been committed:

You will be in positions that matter. Positions in which you can decide the

nature and quality of other people’s lives. Your errors may be irrevocable.

So when you enter those places of trust, or power, dream a little before you

think, so your thoughts, your solutions, your directions, your choices about

who lives and who doesn’t, about who flourishes and who doesn’t will be

worth the very sacred life you have chosen to live. You are not helpless.

You are not heartless. And you have time.

Thank you.