Abstract:

Amidst other popular artists, Wu-Tang Clan is a “revolutionary force in hip-hop” that has “changed both the sound and business of rap music forever” and impacted artists like Pulitzer Prize–winning Kendrick Lamar. [1] On the other hand, the Five Percent Nation (also known as the Five Percenters or Nation of Gods and Earths), a Black nationalist religious organization based in New York City, remains enigmatic save for occasional articles which denigrate the group. This project pinpoints how Wu-Tang Clan incorporates and interprets Five Percent Nation ideologies in their iconic 1993 debut album. Drawing upon relevant scholarship in the area of hip-hop and religion studies, alongside Wu-Tang interviews and official Five Percenter websites, the ensuing analysis illuminates how the album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), maps selected Lessons and concepts of the Five Percent Nation. Surveying specific ideas, this article connects Wu-Tang Clan’s inclusion of kung fu to the Five Percenter idea of the “Asiatic Black man.” The reinforcement of this bridge between Wu-Tang and the Five Percenters gestures to the larger, undeniable impact the religious organization made on the hip-hop genre, especially in the early years of hip-hop.

Introduction

“About 80 percent of hip-hop comes from the Five Percent … In a lot of ways, hip-hop is the Five Percent.”—RZA [2]

“Who is the Original Man? The original man is the Asiatic Black man; the Maker; the Owner; the Cream of the planet Earth, Father of Civilization, God of the Universe.”—Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1 [3]

Over 25 years after their debut album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan maintains their legendary status. [4] Hip-hop scholar Brian Coleman agrees with this when listing “the impact, the illness, the innovation, the size, and the longevity” of Wu-Tang, while BBC writer Kieran Nash praises the group as a “revolutionary force in hip-hop” that “changed both the sound and business of rap music forever.” [5] Confronted with the realities of gang culture, poverty, and racist infrastructure policies present in late 20th-century New York City, Wu-Tang responded with bombastic lyricism and rhetoric which hearkened to their then-common religious affiliation: the Five Percent Nation (also known as the Five Percenters and Nation of Gods and Earths). [6] The hip-hop group’s more recent popularity permeates contemporary visual media as the story of Wu-Tang Clan is told to a younger generation of listeners who were not born at the beginning of Wu-Tang’s career. Such media includes Showtime’s Of Mics and Men (2019), a four-part documentary chronicling the rise of Wu-Tang and their complicated group dynamics, and the Hulu series Wu-Tang: An American Saga (2019), “an epic bildungsroman and dank autofiction” about the formation of Wu-Tang. [7]

Wu-Tang Clan’s rising prevalence in popular media participates in and reinforces the prominence of hip-hop music in the United States. Though hip-hop is a national and international phenomenon, it began in August 1973 in the West Bronx, New York, at a party DJ’d by then-teenaged Jamaican immigrant Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell. [8] The motive was practical, throwing a party to make back-to-school shopping money for his sister and party host Cindy. The result: a new, exciting genre and culture that “stripped down and let go of everything” in music, save for “the rhythm, the motion, the voice, the name.” [9] Over the next four years, this primordial hip-hop spread to other New York City boroughs, spawning acts like Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa. The citywide blackout on July 13, 1977, enabled the looting of new sound systems and equipment key to DJing, thus “boosting the authority” of aspiring hip-hop artists. [10] Hip-hop permeated New York City. Then, in 1979, it broke into the mainstream with the release of “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang, the fifteen-minute record which both captured the vivacity of live hip-hop and became the first rap song to enter “the American Top 40” for popular music. [11] In six years, a teenager’s hobby became an international sensation.

If the 1970s saw the birth of hip-hop, the following decade was its adolescence. The 1980s demonstrated the flexibility of the genre, commercial hip-hop dividing into subgenres like party hip-hop, gangsta rap, conscious rap, and more (with some overlap across types). It is in part for the sonic diversity of this era that scholars like Tricia Rose claim, implicitly and explicitly, that much of the ’80s (and, in some cases, the early ’90s) constitute hip-hop’s “Golden Age.” The common thread of this expanding genre is Islamic Black nationalist rhetoric and infusion from the Nation of Islam (NOI) and the Five Percent Nation (or Nation of Gods and Earths) specifically. [12] The aforementioned artist Afrika Bambaataa, a “hip-hop pioneer,” connected with NOI and harnessed that influence in creating the Zulu Nation to “spread socially and politically conscious ideas and ideals.” [13] Meanwhile, rapper Rakim Allah, considered “one of the most influential rappers in the history of hip-hop,” joined the Five Percenters in 1985, which undeniably influenced his debut album with Eric B., Paid in Full, two years later. [14] Bambaataa and Rakim evidence the claim that, at least for the beginning of the genre, Islam is hip-hop’s “official religion.” [15]

Within this musical and religious context, Wu-Tang Clan formed in Staten Island, New York. Prior to formation, cousins Robert F. Diggs (RZA or The RZA), Gary Grice (GZA), and Russell Jones (Ol’ Dirty Bastard) produced music together as the group All In Together Now. [16] All three were also members of the Five Percent Nation, each with a “righteous name” (Prince Rakeem, Allah Justice, and Unique Ason Allah respectively) and mastery of the 120 Lessons. Over time, RZA, GZA, and ODB expanded their ranks to include Clifford Smith (Method Man), Corey Woods (Raekwon), Dennis Coles (Ghostface Killah), Jason Hunter (Inspectah Deck), Lamont Hawkins (U-God), and Elgin Turner (Masta Killa). [17] These six members joined for their own reasons, like Inspectah Deck and U-God, who found RZA and left “selling crack” to pursue hip-hop instead. [18] Once the group garnered its members, they set out as the Wu-Tang Clan to accomplish a feat uncommon at that time: sign a record deal as both a group and nine individuals in order to pursue group outings and solo ventures. Their first project as Wu-Tang in 1993 juxtaposed Five Percent Nation thought alongside East Asian influence, introduced to the hip-hop group through kung fu movies. The result: the album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), a religious perspective on living in New York City during that time as young Black men.

It is important to note that the Five Percenters “reject association with the religion of Islam” and “describe their value system as a culture, not a religion,” a “way of life” embodied in daily living. [19] While the organization rejects “religion,” religious studies scholar Catherine L. Albanese provides a functional definition of religion which accommodates these considerations. Albanese recognizes that “religion is a matter of practice, an action system” and breaks down religion into four connected parts: creed, code, cultus, and community. [20] She therefore defines religion as “a system of symbols (creed, code, cultus) by means of which people (a community) orient themselves in the world with reference to both ordinary and extraordinary powers, meanings, and values.” [21] With this in mind, terms like “Islam” when used to describe the Five Percenters denotes the shared “creeds” and rhetoric between them, the Nation of Islam, and Sunni Islam, especially pertaining to hip-hop.

U-God describes it best when he claims that the “knowledge and experience” from the Five Percenters “provided the foundation” for the Wu-Tang Clan. [22] Despite this claim, it is rare that even biographical texts examine the group’s association with the Five Percenters. Mainstream news articles and reports associate the Five Percenters with criminal activity, making it more surprising that the elusive organization entered mainstream consciousness through, among other artists, Wu-Tang Clan. [23] Clarence 13X Smith founded the organization in 1964 and gained a following among local poorer Black people, providing services for fellow Harlem residents and “teaching the Supreme Wisdom Lessons [of the Five Percenters] to Harlem youth.” [24] Nevertheless, Five Percenters “were labeled a gang from their inception” by a combination of “various state and federal law enforcement agencies.” [25] A year after the founding of the Five Percenters, the Federal Bureau of Investigation opened its investigation report on the organization with this succinct description which completely ignores its religious core: “‘Five Percenters’—a loosely knit group of Negro youth gangs in the Harlem section of New York City.” [26] Decades later, the news media still describes the religious group as “a virulently racist black group” associated with violent crime. [27]

After the assassination of its leader in 1969, the organization continued its existence while being influenced in part by “Brooklyn turf gangs, Queens drug empires, conscious hip-hop, [and] prison culture.” [28] The 1970s provided time for the Five Percent Nation to expand beyond the bounds of Harlem to other New York City boroughs. In some instances, the ideology gained purchase among organized criminals and drug hustlers. One such group was the “Linden Boulevard posse,” known for both rushing “headlong into fights with knives and guns drawn” and claiming “affiliation” with the Five Percenters. [29] Whether these claims of affiliation understood “Five Percenter ideology less as a religion and more as a rebellious pose,” or took on the religious organization’s “way of life,” Five Percenters brought the ideology into contexts which reinforced notions of themselves as gang-affiliated or dangerous. [30] In 1993, 36 Chambers provided a glimpse into this complex connection between religiosity and criminal association, as Wu-Tang interspersed references to violence and illicit substance use between the album’s glimpses of deeper Five Percent Nation principles.

I begin my analysis of 36 Chambers by recognizing and denoting here my position as a nonmember of the Five Percent Nation. As an outsider, I take the position of musicologist Felicia Miyakawa in her similar research because “my perspective is limited, subject to the availability of sources, and influenced no doubt by my own theological upbringing.” [31] At the same time, my work presents an opportunity to counteract the legacy of misrepresenting the Five Percenters as either a criminal organization or at minimum gang-affiliated. This article draws on direct quotations from current and former members of the Five Percent Nation, found on now-inactive online sites and texts focused on the group, since as a nonmember my access to core documents and member perspectives is limited. Exposure to scholarly studies and primary sources provides tools I use to decode and analyze Wu-Tang lyrics. These insights and excerpts inform my interpretations of Wu-Tang’s debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), benefitting from Wu-Tang’s own interpretations offered in texts and interviews by members like RZA and U-God.

Interdisciplinary scholar Imani Perry’s Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop provides my foundational understanding for parsing meaning in hip-hop lyricism. Perry makes the critical jump from an isolated investigation of religious imagery to relating the lyrical “poetics” in connection to influential “politics” on micro and macro levels. She articulates rap lyrics as layered with meaning embedded by the artist, with each layer occurring simultaneously as to privilege those who understand the “slang,” the performer’s home city or neighborhood, and the “sub-textual critique of society.” [32] Given this foundation, it is evident that 36 Chambers’ songs present an opportunity to reveal hidden messages and communications about subjects like the doctrine of the Five Percent Nation. Musicologist Felicia Miyakawa offers this kind of analysis in her 2005 text Five Percenter Rap: God Hop’s Music, Message, and Black Muslim Mission, after which this article models itself. Whereas Miyakawa examines iconic lyrics from the hip-hop pantheon and illuminates the nuances of the religious group, this project analyzes one album as a collection of Five Percenter thought in the little-known religious history of Wu-Tang Clan.

Hip-hop scholar Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation details the development of hip-hop from 1968 to 2001, providing much information concerning New York City during the 1990s. Scholars in the field of hip-hop and religion studies, pioneered by Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn, fill in the gaps in Chang’s analysis regarding the integral role of religion in the genre. Josef Sorett contextualizes the incorporation of Five Percent Nation doctrine in hip-hop within a timeline he proposes in his piece, “Believe Me, This Pimp Game Is Very Religious: Toward a Religious History of Hip Hop.” Here, he argues that early hip-hop utilizes various forms of Islam and more contemporary hip-hop engages Christianity. [33] Where Sorett and Chang offer albeit brief gestures to Five Percenter “question-and-answer studies and keyword glossary forms” and name the group as one of many “various forms” of Islam, anthropologist H. Samy Alim provides side-by-side comparisons between the Five Percent Nation, NOI, and Sunni Islam as they appear in hip-hop. [34] These scholars in aggregate produce a detailed image of the environment of Wu-Tang and 36 Chambers, a religiously infused hip-hop landscape shaped by policies which disproportionately impact people of color during the 1980s through the 1990s.

This larger understanding frames Michael Muhammad Knight’s historical view of both the Five Percent Nation and Wu-Tang Clan’s career, in his 2007 book The Five Percenters: Islam, Hip Hop and the Gods of New York. In particular, Knight describes the formation of Wu Tang Clan, how each member differently lived out their shared Five Percenter ideology, and the complicated relationship between Five Percenters and hip-hop (especially Wu-Tang Clan). Miyakawa also provides a brief, yet expansive history of the Five Percent Nation, describing connections between the organization and previous Black Islamic groups in the United States. This history supports her subsequent lyrical breakdowns of various rappers who incorporate Five Percenter rhetoric in their lyrics. Over the course of these breakdowns, Miyakawa presents excerpts of key Five Percenter concepts and texts, including the Supreme Alphabet, Science of Supreme Mathematics, and Lost-Found Lessons. [35]

Together, these texts provide the context within which I analyze 36 Chambers. To foreground Wu-Tang’s analyses of their music, as well as their understanding of themselves, this article pulls from their interviews and various texts. Brian Coleman’s anthology of hip-hop artists/groups and their iconic albums presents song-by-song commentary on Wu-Tang’s debut album by Wu-Tang themselves. Knight’s The Five Percenters also contains interview content from Wu-Tang, juxtaposed with Five Percent Nation opinions about the group. Thanks to the recent increased popularity of the hip-hop group, Wu-Tang Clan has engaged in more interviews about their lyrics and perspectives on music in their various albums, including 36 Chambers. Their most recent notable commentary on the Wu-Tang musical process comes in Showtime’s Of Mics and Men, which includes footage from as early as the 1990s and current reflections by current members and affiliated parties. Outside the interview context, members U-God and The RZA have produced texts detailing their perspectives on Wu-Tang and Five Percenters.

Due to the Five Percent Nation’s position as branching from the Nation of Islam (NOI), much of the language, lessons, and theology remain the same across the two groups. When Clarence 13X Smith left NOI to found the Five Percenters in Harlem in the mid-1960s, he took core NOI Lessons and added aspects of numerology and other ideologies. [36] One common foundational belief shared between the two organizations is that “all humanity descended from the Black race,” with other ideas and terms common to Islam like “Allah” and prophets. [37] The name “Five Percent Nation” comes from how the Five Percenters emphasize a specific set of Lessons shared with NOI, Lost-Found Lesson no. 2, questions 14 through 16:

14. Who are the 85 percent? The uncivilized people; poison animal eaters; slaves from mental death and power; people who do not know who the Living God is, or their origin in this world and who worship that direction but are hard to lead in the right direction.

15. Who are the 10 percent? The rich slave-makers of the poor, who teach the poor lies to believe: that the Almighty, True and Living God is a spook and cannot be seen by the physical eye; otherwise known as the bloodsuckers of the poor.

16. Who are the 5 percent? They are the poor righteous teachers who do not believe in the teachings of the 10 percent and are all-wise and know who the Living God is and teach that the Living God is the Son of Man, the Supreme Being, or the Black Man of Asia, and teach Freedom, Justice and Equality to all the human family of the planet Earth; otherwise known as the civilized people, also as Muslims and Muslim Sons. [38]

The acknowledged presence of these two forms of Islam as well as Sunni Islam in hip-hop over the decades highlights the necessity of identifying specific differentiating attributes of the Five Percent Nation. [39] Two aspects which characterize the Five Percenters are the Science of Supreme Mathematics and the Supreme Alphabet, both of which assign special meanings for the digits 0–9 and the A–Z alphabet. [40] Numerical sequences, isolated letters, and/or the pairings of letters or digits with their corresponding meanings may therefore denote the presence of Five Percent Nation ideology. Other telltale signs of the Five Percenters include gender titles (Black men as “Gods” and Black women as “Earths”), inclusion of numbered questions and answers (the format of teaching lessons to practitioners), and the outright mention of the “Five Percent Nation” and/or “Five Percenters.” This article employs these identifiable metrics to distinguish invocations of the Five Percent Nation from normative Islamic and more generally religious rhetoric.

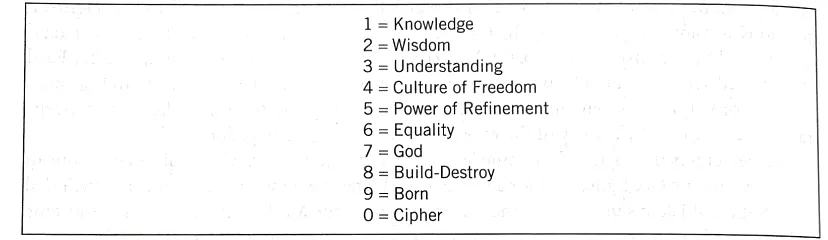

Figure 1. Since of Supreme Mathematics, with each digit signifying an idea. [41]

Because Smith founded the Five Percent Nation in the 1960s, “the Five Percenters’ unique terminology and language … [had] entered into the street slang” of New York City by the time Wu-Tang Clan created Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). [42] Examples of this phenomenon include the phrase “What up, G?,” originally the “What up, God?” greeting among Five Percenters; “the affirmations ‘word’ and ‘word is bond,’” derived from the organization’s Lessons; and terms like “cipher,” “dropping science,” and “break it down.” Wu-Tang uses these slang terms in songs like “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber” and “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin ta Fuck With.” Going beyond isolated slang phrases, 36 Chambers incorporates specific doctrinal ideas, practices, and frameworks in a manner which maps several characteristic elements of the Five Percenters. The ensuing analysis demonstrates not only the complex doctrine of the Five Percenters but how Wu-Tang translates them to the hip-hop context.

“The God left lessons on my dresser”—Ghostface Killah [44]

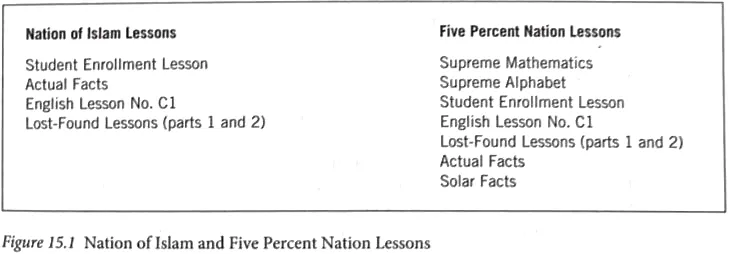

Through the 1990s, the Five Percenters existed as an “idiosyncratic mix of Black nationalist rhetoric, Kemetic (ancient Egyptian) symbolism, Gnosticism, Masonic mysticism, and esoteric numerology.” [45] This “mix” list describes the seven core Lessons of the organization, presented in a specific order through which initiates learn and memorize them. [46] The difference in Lesson order is noteworthy between NOI and the Five Percent. The Nation of Islam begins its pedagogy with Student Enrollment Lesson, orienting initiates with key conceptions of “the population[s] of various ethnic groups, the measurements of the earth, and the origins of mankind.” [47] Student Enrollment Lessons, English Lesson No. C1, and Lost-Found “(Moslem)” Lessons (parts 1 and 2) take a question-answer form, totaling 120 in number. These three Lessons, plus Actual Facts, constitute both the majority of Five Percenter Lessons and the entirety of NOI Lessons which Clarence 13X Smith took with him. The Five Percent differentiates themselves by beginning with their original numerologies, thereby positioning their religious organization as “a mathematics-based science, a way of life and not a traditional religion.” [48] Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) omits Actual Facts and Solar Facts, which apply Supreme Mathematics to the features and measurements of the Earth as well as the distances of the planets from the sun respectively to uncover “revelations of higher truths,” in their entirety and rarely mentions any of the seven Lessons by name. [49] 36 Chambers refers only to one Lesson by name: Supreme Mathematics, the first Five Percenter Lesson.

Figure 2. Nation of Islam and Five Percent Nation Lessons. [50]

“Thoughts that bomb shit like math”—Raekwon [51]

Upon a first listen, Raekwon’s claim to “bomb shit like math” in the lead single for 36 Chambers, “Protect Ya Neck,” can appear absurd, as normative math (i.e., addition, subtraction, etc.) does not in and of itself bring explosions. The lyrics speak not of arithmetic or other mathematical practices but of the Science of Supreme Mathematics, as RZA deciphers the line as describing the explosive “wisdom in the Divine Mathematics.” [52] For Five Percenters, the power of this “wisdom” exists as Supreme Mathematics. It “is the key to understanding man’s relationship to the universe,” using its numbers and associated meanings to “break down and form profound relationships between significant experiences within life.” [53] Practitioners use the digits 0–9 with their pre-assigned values to ascribe meaning to ages, dates, distances of planets from the Sun, and more to, in part, better understand “why life was so hard and cold for the blackman and other significant facts of life.” [54] Beyond breakdowns, the first three digits help categorize the 120 Lessons initiates must learn into three sections: “knowledge,” “wisdom,” and “understanding” necessary to become a Five Percenter. Raekwon invokes the power of this practice, speaking of his lyrical prowess and ability to defeat other rappers, breaking them down similar to Five Percenters breaking down numbers. Wu-Tang gestures to these practices and molds them to hip-hop implications.

Just as Raekwon uses Supreme Mathematics to emphasize his rap capabilities, RZA describes Wu-Tang musical power as “three-hundred and sixty degrees of perfected styles.” [55] This references the “0” digit, which follows “9” in the Supreme Mathematics and refers to the concept “cipher.” As the final digit of the Supreme Mathematics, “cipher” signifies the ability to understand everything and achieve full “knowledge,” “wisdom,” and “understanding” concerning the universe. Just as “0” is a complete circle, a 360-degree shape with this attached meaning, RZA claims Wu-Tang’s combined style of rapping encompasses the full, complete power of hip-hop/music. Outside of hip-hop braggadocio descriptions, the group uses this doctrine to reference inebriating substances. For instance, in “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber,” Ghostface Killah talks about getting his “Culture Cipher.” [56] Knowing that “culture” is the meaning of “4” and “cipher” is the meaning of “0” transforms this enigmatic statement into Ghostface Killah getting a “40.” A “40” in this case refers to a 40-oz. bottle of alcohol.

The accompaniment to the Science of Supreme Mathematics is the Supreme Alphabet, both of which were created by Father Allah to uncover “divine knowledge.” [57] Like the Supreme Mathematics, the Supreme Alphabet assigns a specific idea to each of the 26 letters in the English language to make connections in the world. The names of RZA and GZA present examples of this meaning-assignment and breakdown. In “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber,” RZA states the ideas associated with each of his name’s three letters: “Ruler Zig-Zag-Zig Allah.” [58] RZA elaborates the meaning of each term:

R = Rule or Ruler. God is the only ruler there is by knowledging his building powers and making them born to all the planets of the universe, so that they can go accordingly with Islam. This is bearing witness to Allah, for he is the ruler of all.

Z = Zig-Zag-Zig. Zig Zag Zig means knowledge, wisdom, and understanding; man, woman, and child.

A = Allah. Allah is the rightful name of Man, which consists of Arm, Leg, Leg, Arm, Head---A.L.L.A.H. Allah is the supreme-being original man from Asia. The sole controller and ruler of the universe, the original man who has knowledge of himself, and to know self is to know all things in existence. [59]

Far from an arbitrary stage-name, Robert F. Diggs taking the RZA moniker assumes an identity rooted in Five Percenter conceptualizations of the divinity of Black men and the 120 Lessons of the organization. Like the hip-hop group’s use of Supreme Mathematics, Wu-Tang applies the practice of alphabetical signification in ways not in accordance with normative Five Percent Nation practice. For example, in the same song, Raekwon states, “We Usually Take All Niggas Garments,” turning the group’s name “Wu-Tang” into an acronym sentence. [60] Wu-Tang again translates a Five Percenter idea to their music and shifts the focus from a further understanding of the universe to the braggadocio of Wu-Tang Clan itself.

“Peace to all the Gods and the Earths”—RZA [61]

Alongside these two numerological practices which differentiate the Five Percent Nation from other forms of Islam in the United States, Five Percenters stress the importance of the family: “The unified Black family is the vital building block of the nation.” [62] The three parts of this family are the men, women, and children, each associated with an astronomical object within a larger framework describing the inner divinity of Black people. Within the religious organization, the Black man “is God and his proper name is ALLAH. Arm, Leg, Leg, Arm, Head.” [63] As RZA declares “peace to all the Gods” in “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin’ ta Fuck With,” so too do Raekwon and Ghostface Killah call each other Gods in “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber.” The notion of the divinity of the Black man is codified in the aforementioned Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1, designating the Black man as “God of the Universe.” [64] As a reminder, Student Enrollment Lesson consists of ten questions and answers concerning, among other matters, “the origin of mankind.” [65] Unlike the Supreme Alphabet and Science of Supreme Mathematics, this understanding of Gods is shared between the Nation of Islam and the Five Percent Nation. It nevertheless remains one of the few aspects of the Five Percenters seen by the public, as the group retains many of its core documents only for members.

RZA’s verse in “Protect Ya Neck” exemplifies a consequence of this “God of the universe” idea. Compared with other similar groups, the Five Percenters host a “looser moral code than is allowed in other Black Muslim sects,” since the organization believes that Gods can best determine for themselves how to live as liberated divine beings. [66] Therefore, just as each Black man in the organization “has the ability to make his own decisions about clothing, use of drugs and alcohol consumption of particular foods, and roles in relationships,” so too can they do this: “Explore all paths and respect the good efforts of others” including “Eastern philosophy” and practices, “Nubian Hebrew movements,” and even Christianity. [67] RZA’s God status enables him to include aspects of another religion with the Five Percenter concepts in 36 Chambers:

Feelin’ mad hostile, ran the apostle / Flowin’ like Christ when I speaks the gospel / stroll with the holy roll … ten times ten men committin’ mad sin / Turn the other cheek and I’ll break your fuckin’ chin … / Be doin’ artists in like Cain did Abel [68]

Like Raekwon invoking the Science of Supreme Mathematics to emphasize his lyrical prowess, RZA incorporates concepts attached to Christianity (e.g., “the apostle,” “Christ,” “the gospel”) to bolster the credibility of his “flow.” The verses of both Wu-Tang members occur in the same song on 36 Chambers, an example of the elasticity of Five Percenter beliefs, a form of “free individualism,” for male practitioners. [69] This appears to be a Five Percenter privilege of being male, with Gods holding the responsibility to teach their Earths. Also, the same critiques of “inconsistency and hypocrisy” for varying moral actions amongst members can apply to beliefs, a potential catalyst for contention within the religious organization. [70]

The Five Percent Nation extends family classification rhetoric to women and children, “speaking of women as Earths, children as seeds, and the family unit in the metaphor of [the] sun, moon, and stars.” [71] Women, called Earths and symbolized as the moon, maintain much responsibility for the nurture of their seeds and general reproduction “because through reproduction a woman symbolizes the life-giving forces of the earth.” [72] According to Wu-Tang, this kind of care extends even beyond the child reaching adulthood and becoming a God, as Inspectah Deck seeks his mother, “the Old Earth,” when he feels “ready to give up” on life. [73] Gods, also symbolized as suns, are responsible for financial and emotional provision as well as for teaching their Earths “the knowledge of self.” [74] This division of responsibility between Gods and Earths, suns and moons, enables RZA to scold a woman in “Protect Ya Neck” for being without her child: “It’s 10 o’clock, ho, where the fuck’s your seed at?” [75] Children are the next generation of practitioners, similar to seeds propagating their plant species, acting as “link[s] to the future” who “must be nurtured, respected, loved, protected and educated.” [76] Because stars appear as small dots of light to the naked eye compared to the sun and moon, the organization also conceptualizes children as stars. Together, Five Percenters believe this configuration of the Black family unit, sun, moon, and stars, emulates “the harmony of celestial bodies.” [77]

“Cash rules everything around me / CREAM, get the money”—Method Man [78]

The uses of “God” in 36 Chambers gesture to Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1, which describes the Black man as “God of the universe.” This specific Lesson also provides an alternative meaning to “cream” in the eponymous Wu-Tang Clan song “C.R.E.A.M.” “C.R.E.A.M.” presents two testimonial verses rapped by Raekwon and Inspectah Deck, both talking in detail about the strife and the difficulty of survival in their New York communities. The prominent motif in these verses is accumulating wealth either through illegal means or involving illicit substances. Raekwon discusses beginning with making money from “drug loot,” proceeding to committing “high stakes” robberies, and mugging “white boys in ball courts” before leaving this life to join the “sick-ass” Wu-Tang Clan. [79] Similar to him, Inspectah Deck describes how he was “a young buck sellin’ drugs and such,” attempting to achieve a class status that he “could not touch.” [80] As a result, Deck is incarcerated and depressed until he encounters the “Old Earth” to guide him. [81] Their collective attempts at making money gesture to the true meaning of “cream” signified by Method Man in the chorus in a form similar to the earlier “Wu-Tang” acronym example: “cream” means “cash rules everything around me.” “Cream” is simultaneously the money for which Raekwon and Deck risk their lives and the larger dominating role money asserts in the lives of Wu-Tang Clan members in Staten Island during the 1990s. [82]

In the Five Percent Nation Lessons, “cream” exists as one of the titles of the “Original” Black man alongside titles like “God of the universe” and “Father of civilization”: “the Cream of the planet Earth.” [83] As “Gods” in the context of the universe and the family unit, Black men in the Five Percenter conception ought to bring control and order to their various domains. Specifically, for “the planet Earth,” the “Cream” helps keep communities under control and thus enables Black youth to flourish and grow in their “knowledge of self.” Therefore, one can read “C.R.E.A.M.” as a story of disorder, in which the artificial “cream” (money and capitalism) supplants the true “Cream” (the Black man and the Black diaspora more broadly). [84] Locating Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1 helps explain why “CREAM” fails for Inspectah Deck as well as why consulting the “Old Earth” aids his reorientation. [85] Faced with a world which follows money to the point of crime, drugs, and danger, Deck needs to learn how the world is supposed to work in order to become free and then “kick the truth to the young Black youth.” [86] In the same way, Raekwon escapes this domination by joining Wu-Tang Clan, which, as mentioned earlier, hosts Five Percenter affiliation at its origin.

“Makin’ devils cower to the Caucasus Mountains”—U-God [87]

Though 36 Chambers does not include allusions to all 120 Lessons of the Five Percent Nation, Wu-Tang’s brief mention of white people illuminates the “ten percent” idea which highlights the role of the Five Percent. In “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’,” U-God proclaims that the force of his “hip-hop” makes “devils” terrified of him. Underscored by U-God’s use of “Caucasus Mountains,” it is clear that the rapper boasts in his ability to scare white (“Caucasian”) people into hiding from musical abilities. Referring to white people as “devils” gestures to Lost-Found Lesson no. 2, question 15, a Lesson of the Five Percent Nation doctrine which comes from NOI, which references those who antagonize the ignorant eighty-five percent of the world and the Five Percenters tasked with educating said ignorant. [88] Prophet Elijah Muhammad of NOI created the idea that “an evil scientist named Dr. Yacub (or Yakub)” created the “white race over six thousand years ago” as “wholly devoid of divinity, a race of pure evil.” [89] The Five Percent Nation’s focus on Black people as the original people reinforces this belief concerning white people, necessitating a separation of Gods, Earths, and seeds from the “race of pure evil.” U-God takes this white inferiority doctrine to bolster the threatening nature of his lyricism, participating in the Five Percenter drive to repel “devils” away from themselves and those who need to be enlightened. It is noteworthy that Five Percenters expand the antithetical “ten percent” into two parts: “the grafted, blue-eyed white devil and those, such as those in the Nation of Islam, who have knowledge and power” but misuse this power. [90] Wu-Tang does not reference this aspect of the “ten percent,” which preserves animosity toward NOI in its creed interpretation.

“From the slums of Shaolin, Wu-Tang Clan strikes again”—GZA [91]

It is clear by now that Wu-Tang Clan’s engagement with Five Percenter concepts in Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) surveys some of the complex doctrines of the Five Percent Nation. Across all of the Lesson references, Wu-Tang manipulates doctrine to boast in personal hip-hop abilities and lyrical expertise. However, examples of incorporating these ideas in hip-hop music is far from unique to Wu-Tang. Beyond Rakim Allah and Wu-Tang Clan, hip-hop artists like Jay Electronica and Nas produced projects early in their careers which translated their Five Percent Nation fidelity into songs, like Jay Electronica’s “Exhibit C” and Nas’s “Life’s a Bitch” featuring AZ. [92] Wu-Tang’s many invocations of East Asia, specifically China, set the group apart from other Five Percenter hip-hop artists. Greater still, these cross-cultural interactions using “Wu-Tang,” “Shaolin,” and samples from kung fu movies exhibit the elasticity of the Five Percenters’ creed. Following the broad overview of the Five Percenter creed and codes, this section focuses on one specific phrase from Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1 to frame the unique kung fu element of 36 Chambers and Wu-Tang Clan as a whole.

“The original man is the Asiatic Black man”—Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1 [93]

Just as NOI and the Five Percenters share some common elements of doctrine, the idea described in the phrase “the Asiatic Black man” emerges in three specific 20th-century movements characterized by a Black racial focus alongside an emphasis on Islam: the Moorish Science Temple, the Nation of Islam, and the Five Percent Nation. Unlike other instances of doctrine invocation in Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), Wu-Tang makes no mention of this aspect of Five Percenter doctrine. However, Wu-Tang’s inclusion of kung fu movie samples and martial arts allusions in lyrics present a consistent juxtaposition of references to Asia (often China specifically) and religious doctrines. The ensuing analysis demonstrates that 36 Chambers and the Five Percent Nation refer to two different ideas when they refer to the Asian continent and “Asiatic” race respectively. That said, the similar vocabulary offers an occasion to discuss not only this concept of the “Asiatic Black man” but the relationship of the Five Percenter organization with earlier Black American Islamic organizations like the Moorish Science Temple and the Nation of Islam.

The first of these three religious organizations, the Moorish Science Temple, emerged in 1913 under founder Timothy Drew, who later changed his name to Noble Drew Ali. [94] Like the Five Percent Nation, the Temple opened itself to key features of other religions, honoring “all the Divine Prophets, Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha and Confucius” on its membership cards. [95] Ali taught, among other matters, that “salvation” for Black people existed “in the discovery by them of their national origin.” Terms like “Ethiopian,” “Negro (Black),” and “Colored” were insufficient, as they signaled “division,” “death,” and “something that is painted” respectively. [96] Instead, according to the Temple, the true origins for Black people were “the descendants of ancient Moroccans” and “the Biblical prophetess Ruth, whose progeny settled in the area known as Moab.” [97] Far from a random people group, Ali understood these “Moroccans” cultivating an expansive civilization at one point stretching from current Morocco “to North, South, and Central America.” The term “Asiatic” thus described the powerful origins of Black people centuries earlier, “Asiatic” acting as a “generic term” denoting “any person not of ‘pale’ hue (i.e., non-Caucasian).” [98] This religious organization maintained that capturing this identity for oneself meant keeping one’s “power,” “authority,” “God, and every other worthwhile possession.” [99] Therefore, to be “Asiatic” was to assume a new story and to take on levels of power otherwise unattainable.

The Nation of Islam, which emerged later in the 20th century, also included the idea of the “Asiatic” with relation to Black Americans. W. D. Fard, later known as Master Fard Muhammad, founded NOI amidst fracturing within Ali’s Temple and gained a strong following by 1933. [100] Within the organization’s understanding of its history, Fard’s father was an “Asiatic Blackman” and he himself was both an Asiatic Blackman and “Allah in person.” Given that Student Enrollment Lesson no. 1, which states that “the original man is the Asiatic Black man,” comes from NOI, it is clear that this group incorporated the “Asiatic” idea in an albeit more intense form. Whereas the Moorish Science Temple stated that Asiatic is the true nationality of Black people and key to unlocking their power, NOI maintained that Black people were the original inhabitants of the world. “Asiatic” moved from one of several nationalities in existence, as with the Temple, to the purest form of humanity in NOI. To be an Asiatic Black man was to be the original, untainted form of humankind, an identity to celebrate instead of denigrate, which contrasted the prominent racist sentiments of the 1930s and onward. Though the two organizations share similar concepts and aspire “to create an identity for African-Americans greater than that offered under the United States flag,” it is important to note that NOI denies “any historical ties with Noble Drew Ali.” [101]

Regarding the Five Percent Nation, it is clearer that Five Percenters drew from their predecessor, NOI. Though it is unclear why founder Clarence 13X Smith left NOI in the 1960s, it is known that he took with him several core documents from the organization, like the Student Enrollment Lesson and the Lost-Found Lessons. As a reminder, the former Lesson set includes the idea of the “Asiatic Black man” as the progenitor of humanity and latter Lessons include those from which the Five Percent Nation derives its name. [102] The Five Percent Nation recognizes the influences of the Moorish Science Temple and NOI and views itself “as fulfilling these generations of resistance theology.” [103] If the Temple sees “Asiatic” as a deeper, truer nationality, and NOI understands it as the human race in its purest form, then the Five Percenters see “Asiatic” as the entrance to a path of unlocking full divinity found with the Science of Supreme Mathematics and Supreme Alphabet. In all three cases, the “‘Asiatic’ umbrella” term unites Black people with “all nonwhite peoples” through a newer, realer identity. [104] Wu-Tang Clan’s invocations of “Shaolin,” “Wu-Tang,” etc., in 36 Chambers accomplish more than reconfiguring their experiences of Staten Island according to the mystical, dramatic experiences of kung fu movies. Indeed, the invocations orient eagle-eared listeners to consider “Asia” as double entendre: the physical location of the movies and the deepest reality in the context of the Five Percenters. In this way, the invitation (or command) to enter the Wu-Tang welcomes listeners to enter the truer realities of humankind.

“Shaolin shadowboxing and Wu Tang sword style”—Shaolin and Wu Tang (1983) [105]

RZA’s aforementioned allusions to Christianity highlight the ability of the Five Percent Nation doctrine to incorporate other belief systems. The plethora of references to Chinese martial arts permeating 36 Chambers present the strongest, most consistent example of Wu-Tang bringing together disparate beliefs with Five Percenter teachings. To be specific, the hip-hop group incorporates 1970s and 1980s kung fu film excerpts and ideas throughout its debut album. Kung fu movies are integral to Wu-Tang Clan. The group named themselves after the “best” sword style of the Wu-Tang martial arts school in the film Shaolin and Wu Tang (1983). [106] Meanwhile, a third of Wu-Tang members derive their names from this type of film. Ghostface Killah’s name comes from “the best, best bad guy ever” in The Mystery of Chess Boxing (1979) called Ghostface Killer, whose level of villainy correlated with the rapper’s scary good “lyrical content.” [107] Masta Killa, the youngest member of the original Wu-Tang group, receives his name from the United States title of The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978), The Master Killer. [108] This film concerns “the young Shaolin monk who trained on each successive level until he attained the thirty-sixth chamber of invincible martial artistry.” [109] RZA explains how even ODB’s moniker refers to the eponymous type of character “in every kung-fu movie … who, no matter what he does, does wrong.” [110] With each name, Wu-Tang takes a character or trope from a kung fu film to reflect the abilities and personalities of its respective rappers.

To focus on the debut album, the name Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) combines the titles of three specific kung fu films: Enter the Dragon (1973), Shaolin and Wu Tang, and The 36th Chamber. Each selection marks a strategic decision which extends beyond personal viewing pleasure, though RZA claims Enter the Dragon as one of his favorite films. [111] As mentioned above, Shaolin and Wu Tang (released in the United States as Shaolin vs. Wu-Tang) provides the inspiration for the group’s name as well as the spelling of “Wu-Tang.” The 36th Chamber offers knowledge of “36 chambers” of Shaolin-style martial arts. Most at stake in this film is the unorthodox and contentious “thirty-sixth chamber,” an addition to the thirty-five-tier regiment by protagonist San-Te, “which was to teach the knowledge of Shaolin to the rest of the world.” [112] The cinematic combination of The 36th Chamber and Shaolin and Wu Tang, alongside The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (1983), offer guiding principles for Wu-Tang Clan and their comprehension of the key concepts of “Wu-Tang” and “Shaolin.” Pertinent to 36 Chambers, The 36th Chamber provides “discipline and struggle” while Shaolin and Wu Tang gives “the virtuosity, the invincible style and technique---plus, the idea that sometimes the bad guys are the illest.” [113] The complete title, therefore, communicates the guiding principles of Wu-Tang derived from concepts of kung fu movies crafted on the Asian continent. These principles frame its constituent songs, samples, and Five Percent Nation invocations within notions of controversy, discipline, and craft.

As evidenced by the prominence of kung fu movies in 36 Chambers and commentary about said movies from Wu-Tang members like RZA, kung fu presents a necessary facet of the meaning-making which occurs in the album. The first words of the album come from Shaolin and Wu Tang and describe the “dangerous” nature of the two eponymous martial arts schools, Wu Tang and Shaolin. [114]While kung fu imparts ideas and concepts to Wu-Tang, many of these lessons remain absent from 36 Chambers. Instead, the hip-hop group focuses on the aforementioned link between powerful hip-hop musicality and “Wu Tang sword style,” neglecting broader explicit analysis of the “discipline,” “virtuosity,” and other principles derived by Wu-Tang. This bears striking similarities to the ways in which the hip-hop group treats Five Percenter Lessons, like the Science of Supreme Mathematics, as tools to hype the lyrical skills of group members. Wu-Tang chose specific kung fu movies for reasons which develop their self-conception and worldview, combining these with Five Percenter numerological and racial considerations. One finds this synthesis located in a mixture of a geographical space and style of martial arts called “Shaolin,” a topic worthy of further investigation.

“I come from the Shaolin slum … the isle I’m from”—Inspectah Deck [115]

The geographical reconfiguration Wu-Tang undergoes by renaming Staten Island “Shaolin” participates in a similar, broader Five Percenter practice of renaming. One iteration of this process exists in both the Five Percent and NOI, replacing one’s last name with “X” because the last name “is considered to be his slave name.” [116] Another part of the process is attaining a new “righteous name” to replace a birth name, to which RZA gestures when he establishes his new name with the Supreme Alphabet. The Five Percent Nation’s founder underwent both processes, from the name Clarence Smith to Clarence 13X and then to (Father) Allah. [117] Within the religious organization, initiates receive new names from their “enlightener” upon attaining “knowledge of self.” [118] Initiates, now equipped with a new “enlightened” identity, instruct others and become enlighteners (or teachers) themselves. Lamont “U-God” Hawkins garnered his name, U-God Allah, from his enlightener named “Dakim.” [119] Similar to RZA’s name, U-God Allah incorporates the Supreme Alphabet’s signification of “U,” which is “Universal” and means “multidimensional, infinite, [and] comprehensive.” [120] The name identifies U-God as a fully aware, divine Black man who can “carry the Ambassador torch” of the Five Percenters “every day.” [121] This system of initiates becoming teachers and enlightening other initiates occurs within Wu-Tang Clan: GZA (Five Percenter name Allah Justice) taught Masta Killa and RZA (Five Percenter name Prince Rakeem), the latter of whom taught ODB (Five Percenter name “Ason Unique”) [122] and Ghostface Killah. [123]

The renaming process occurs also with geographical locations, specifically with areas in and around New York. Just as Clarence 13X changed his name to Allah to adhere to his Five Percenter doctrine, Father Allah changed the names of New York City boroughs and surrounding areas to those of important Islamic locations. Raekwon references this when he claims, “In Medina, yo, no doubt, the God got crazy clout.” [124] Far from talking about a Black man in the Saudi Arabian city with specific significance related to the Prophet Muhammad, the Wu-Tang member speaks of either Brooklyn or the Bronx. [125] Five Percenters also call Harlem “Mecca” and even have a name for New Jersey, “New Jerusalem.” [126] These spaces in the Middle East, Medina, Mecca, and Jerusalem, exist as sacred spaces for Muslims who adhere to the Qur’an and the various narratives concerning the Prophet Muhammad. The Five Percent Nation relocate these locations, situated on the Asian continent, with attention to the places important in the history of the religious organization in and around New York City. For example, the name “Mecca,” where the Prophet Muhammad founds Islam, corresponds with the borough in which Father Allah founds the Five Percent Nation. In bringing this portion of “Asia” to the United States, these Middle Eastern cities to New York and New Jersey, the religious organization simultaneously legitimizes itself as well as embeds more impoverished areas with higher cultural significance.

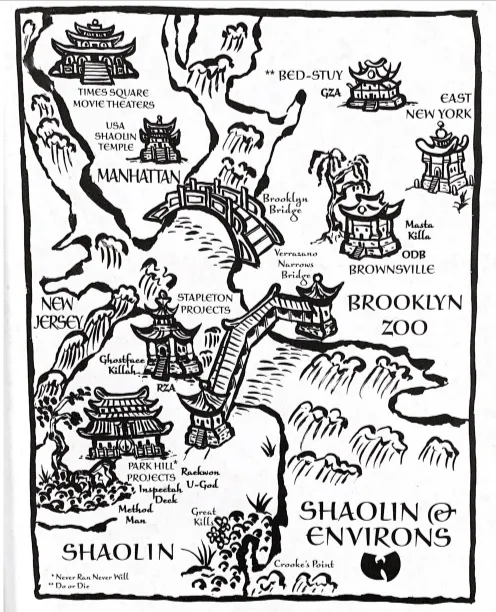

The name “Shaolin” behaves in this way as Wu-Tang Clan’s new name for Staten Island. Wu-Tang describes this particular borough and other New York City boroughs in negative terms: “the crime side, the New York Times side” where there are “stick-up kids, corrupt cops, and crack rocks.” [127] The group pinpoints endemic violence and crime in the areas of the projects in which Wu-Tang members matured. Incorporating the ideas and rhetoric surrounding the “Shaolin” reimagines the crime and violence in terms of those aforementioned kung fu movies. Just as the Wu-Tang conceptualization of kung fu movies contains many factions of people with different styles and methods (e.g., Wu-Tang sword style), so too does this New York “Shaolin” provide alternatives to gun violence and drug use through the lyrical violence of hip-hop. RZA transforms this renaming and relocation practice into a physical map, ignoring normative notable New York landmarks to instead present impoverished housing projects and areas significant to Wu-Tang (e.g., the Times Square Movie Theaters and USA Shaolin Temple). The visual map depicts these project housing units in the style of ancient Chinese architecture, reimagining those impoverished areas as important landmarks of the landscape. Ultimately, “Shaolin” at once exemplifies a Five Percent Nation practice while incorporating a Chinese mythos located in kung fu movies.

Figure 3. A map of Staten Island (Shaolin), Manhattan, and Brooklyn (Brooklyn Zoo) emulating East Asian art. [129]

The transformation of Staten Island into “Shaolin” in 36 Chambers provides new identities for Wu-Tang Clan at the cost of reinforcing certain orientalist conceptions about “Asian” culture. Combining Five Percenter ideology with the principles and techniques gleaned from kung fu movies fulfills a desire “for a creative form of self-defense that exercise[s] and liberate[s] both mind and body.” [130] The self-liberation achieved through mastering the 120 Lessons compounds itself with hip-hop musical skill as an outlet for lyrical violence rather than physical harm. Meanwhile, 36 Chambers’ implicit perspective in the 1990s on the Asia of these kung fu movies imagines it as a “static” landscape untouched by the technologies and drugs which permeate the boroughs of New York for Wu-Tang. [131] Wu-Tang escapes the chaotic 20th century by traveling to a centuries-old cultural practice involving the “Wu-Tang” and “Shaolin.” Granted, 36 Chambers resists grouping all the kung fu schools and styles into one category, distinguishing in its opening words “Shaolin shadowboxing” from “Wu Tang sword style.” And the album presents an educational opportunity for listeners learn about some nuances of kung fu film and martial arts. It remains necessary to recognize the most distinguishing characteristic of Wu-Tang Clan, evident in their debut album, as complicit in orientalist discourse.

Conclusion

It is clear that Wu-Tang Clan made intentional efforts to include and gesture toward the complex Lessons of the Five Percent Nation in Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), drawing attention to the numerologies, gender conceptualizations, and racial ideas which characterize the religious organization. Specifically, Wu-Tang’s use of kung fu movies and ancient Chinese influences illuminates the core idea that the Black man originates in “Asia.” This unique characteristic of the hip-hop group also highlights the loose, inclusive character of the Five Percenter creed. These are the ways in which “hip hop remains the public face of the Five Percent,” providing a public platform through which practitioners dispense their doctrines. [132] Fighting against the history designating the organization as a gang, or else gang-affiliated, Wu-Tang exposes the system of symbols at the core of the organization. In this way, 36 Chambers is a 1993 intervention in the reports, investigations, and news stories about the Five Percent Nation which originate in the mid-1960s and continue through the turn of the 21st century.

As Wu-Tang’s debut album reframes the much-maligned Five Percent Nation for the public, the religious organization maintains a skeptical posture toward Wu-Tang and hip-hop as a whole. Knight best describes this situation as follows: “Many Gods and Earths see [hip-hop] as problematic that musicians are embraced by youth as doctrinal rhetors, particularly given the genre’s common treatment of Black women.” [133] This concern of the Five Percent Nation exists specifically with relation to Wu-Tang “for promoting an image that associates Five Percenters with drugs, alcohol, crime, and the objectification of women.” [134] Given how Wu-Tang uses the organization’s distinct numerology to discuss drinking alcohol and links the Science of Supreme Mathematics to explosive warfare, the Five Percenters’ hesitancy appears well justified. 36 Chambers highlights complex doctrine while re-contextualizing it as the means for boasting about lyrical prowess and clout, far from the purposes intended by the Five Percent. The inclusion of doctrine in the album provides, then, both a service to nuanced public knowledge of Five Percenter and a disservice to the credibility of the organization’s beliefs and texts. Therefore, instead of serving as the perfect embodiment of the Five Percent Nation, 36 Chambers provides an entryway through which one can examine aspects of the Five Percenters.

The presence of Five Percenter ideas in the commercially successful and impactful 36 Chambers is far from an anomaly. While the hip-hop group’s discography boasts six studio albums alongside various mixtapes and collaborative projects, 36 Chambers is the earliest example of the Five Percenter conception which emphasizes East Asian influences. Further study can extend this analysis to other releases in Wu-Tang Clan’s decades-spanning discography, like their second album Wu-Tang Forever (1997). In general, Five Percenter ideology has existed on the airwaves in various forms since the birth of conscious rap. The early work of hip-hop artists like Andre 3000 and Nas presents opportunities for further investigation, as these artists were affiliated with the religious organization for at least a portion of their careers. A deeper analysis of this organization and their positive impact in the United States and hip-hop music would further counter negative narratives in circulation about the New York–based religious group for over fifty years.

RZA claims that “about eighty percent of hip-hop comes from the Five Percent.” This article does not verify the truth of this statement. However, the work accomplished in this piece emphasizes the importance of the Five Percent Nation on the entire genre, from its influence on early hip-hop slang to its role in shaping the iconic Wu-Tang Clan debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Today, hip-hop is at its greatest heights in the United States, becoming the country’s most popular music for the first time in the genre’s near-fifty-year existence. [135] Accompanying this status is widespread hip-hop influence, heard in genre-busting songs like Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” (the remix featuring country music icon Billy Ray Cyrus), and an increased Christian presence in the genre. This is evident in the recent high-profile releases of Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book (2016) and Kanye West’s Jesus is King (2019). As this article demonstrates, the current prominence of Christianity rests upon the previous inclusions of Islam and the Five Percent Nation more specifically. 36 Chambers over 25 years later still showcases the Five Percenters, their creed, and their codes in ways often neglected in the present day. Ultimately, the invitation of the album to “Enter the Wu-Tang” doubles as a doorway for listeners to enter the sonic landscape of “Shaolin” and enter the world of the Five Percent Nation.

Endnotes

[1] Kieran Nash, “How Wu-Tang Clan Revolutionized Hip-Hop Forever,” BBC, April 26, 2019, www.bbc.com/culture/story/20190426-how-wu-tang-clan-revolutionised-hip-hop-forever. In 2015, Kendrick Lamar performed his new single “i” on Saturday Night Live, with his hair and demeanor paying homage to the unhinged performances of Wu-Tang member Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Watch the performance here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=sop2V_MREEI.

[2] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual (New York: The Penguin Group, 2005), 43.

[3] Felicia Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap: God Hop’s Music, Message, and Black Muslim Mission (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2005), 47.

[4] For the duration of this article, I also refer to Wu-Tang Clan’s 1993 album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) in shorthand as 36 Chambers.

[5] Brian Coleman, Check the Technique: Liner Notes for Hip-Hop Junkies (New York: Villard Books, 2005), 450; Nash, “Wu-Tang Clan.”

[6] Several texts offer nuanced descriptions of this period, including Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation, and Ethan Brown’s Queens Reigns Supreme: Fat Cat, 50 Cent, and the Rise of the Hip-Hop Hustler.

[7] Troy Patterson, “Four Shows at the Center of a Golden Age of Hip-Hop Television,” New Yorker, November 1, 2019, www.newyorker.com/culture/on-television/four-shows-at-the-center-of-a-golden-age-of-hip-hop-television.

[8] Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), 67.

[9] Chang, Can’t Stop, 85.

[10] Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Part Sixteen: Cultural Integration 1969–1979,” in Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History 1513–2008 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 401.

[11] Chang, Can’t Stop, 131.

[12] Josef Sorett, “Believe Me, This Pimp Game Is Very Religious: Toward a Religious History of Hip Hop,” in The Hip Hop and Religion Reader, ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn (New York: Routledge, 2015), 237.

[13] H. Samy Alim, “Re-inventing Islam with Unique Modern Tones: Muslim Hip Hop Artists as Verbal Mujahidin,” in The Hip Hop and Religion Reader, ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn (New York: Routledge, 2015), 187.

[14] Chang, Can’t Stop, 258.

[15] Alim, “Re-inventing Islam,” 185.

[16] Michael Muhammad Knight, The Five Percenters: Islam, Hip Hop and the Gods of New York (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007), 184. In this paper, I will also abbreviate Ol’ Dirty Bastard to ODB.

[17] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 2–36.

[18] Coleman, Check the Technique, 454.

[19] Knight, The Five Percenters, xiv, 8; Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 23.

[20] Catherine L. Albanese, Introduction to America: Religions and Religion, 2nd ed. (Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1992), 9–10.

[21] Albanese, “Introduction,” 11.

[22] Lamont “U-God” Hawkins, RAW: My Journey into the Wu-Tang (New York: Picador, 2018), 35.

[23] Knight, The Five Percenters, xiv.

[24] Ibid., xiii. When Smith leaves NOI and creates the Five Percent Nation, he changes his name to Allah and his followers call him Father Allah. As such, I will use the title derived from his followers when describing his doctrine. In my discussions of the historical figure, I will call him Clarence 13X Smith.

[25] Ibid., 142; Juan M. Floyd-Thomas, “A Jihad of Words: The Evolution of African American Islam and Contemporary Hip-Hop,” in The Hip Hop and Religion Reader, ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn (New York: Routledge, 2015), 181.

[26] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “The Five Percenters” (BUFILE: 157-6-34, 1980), 2.

[27] Mark Goldblatt, “Hip Hop’s Grim Undertones,” USA Today, October 29, 2002, usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/2002-10-29-oped-goldblatt_x.htm.

[28] Knight, The Five Percenters, 260.

[29] Ethan Brown, Queens Reigns Supreme: Fat Cat, 50 Cent, and the Rise of the Hip-Hop Hustler (New York: Anchor Books, 2005), 8.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 23.

[32] Imani Perry, Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2004), 31.

[33] Note in my text that I adhere to the definition of “hip-hop” as consisting of four key facets, one of which is MCing or rapping. The other three parts are DJing, break dancing, and graffiti art. Chang, Can’t Stop, 3.

[34] Ibid., 106; Sorett, “Believe Me,” 235. For more information about Alim’s comparison of these three forms of Islam in hip-hop, read H. Samy Alim’s article “A New Research Agenda: Exploring the Transglobal Hip Hop Umma.”

[35] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 44.

[36] Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 172.

[37] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 32.

[38] Ibid., 28.

[39] H. Samy Alim, “A New Research Agenda: Exploring the Transglobal Hip Hop Umma,” in The Hip Hop and Religion Reader, ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn (New York: Routledge, 2015), 55.

[40] See Figure 1 for the Science of the Supreme Mathematics.

[41] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 26.

[42] Knight, The Five Percenters, xiii–xiv.

[43] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 41; The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 43.

[44] Genius. “Can It Be All So Simple / Intermission.” Accessed February 14, 2020, genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-can-it-be-all-so-simple-intermission-lyrics.

[45] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 23.

[46] See Figure 2 for a complete list of the seven Five Percent Nation Lessons alongside the four NOI Lessons.

[47] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 24.

[48] Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 173.

[49] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 24, 26–7.

[50] Ibid., 25.

[51] Genius. “Protect Ya Neck.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-protect-ya-neck-lyrics. The lyrics are as follows: “‘Cause I came to shake the frame in half / With the thoughts that bomb shit like math.”

[52] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 139.

[53] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 25.

[54] See Figure 1; Ibid.

[55] Genius. “Clan in da Front.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-clan-in-da-front-lyrics.

[56] Genius. “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-wu-tang-7th-chamber-lyrics.

[57] Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 173.

[58] Genius, “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber.”

[59] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 46–7. Boldface added.

[60] Genius, “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber.”

[61] Genius. “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin’ ta Fuck With.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-wu-tang-clan-aint-nuthing-ta-fuck-wit-lyrics.

[62] “What We Teach,” The 5% Network, modified January 1, 2005, web.archive.org/web/20050101085428/http://www.ibiblio.org/nge/.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 47. For the complete quotation, see page 1.

[65] Ibid., 24.

[66] Ibid., 31.

[67] Ibid., 33; Knight, The Five Percenters, 10.

[68] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 142.

[69] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 32.

[70] Ibid., 33.

[71] Ibid., 64.

[72] Ibid., 34.

[73] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 152; Genius. “C.R.E.A.M.” Accessed March 6, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-cream-lyrics.

[74] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 33.

[75] Genius, “Protect Ya Neck.”

[76] The 5% Network, “What We Teach.”

[77] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 27.

[78] Genius, “C.R.E.A.M.”

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid.

[82] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 128.

[83] See the full quotation on page 1.

[84] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 53.

[85] Genius, “C.R.E.A.M.”

[86] Ibid.

[87] Genius. “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-da-mystery-of-chessboxin-lyrics.

[88] See the full articulation of the “five percent,” “ten percent,” and “eighty-five percent” populations on page 10.

[89] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 14.

[90] Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 172.

[91] Genius. “Method Man.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-method-man-lyrics.

[92] Knight, The Five Percenters, 186; Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 177.

[93] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 47.

[94] Arthur Huff Fauset, “Chapter V: Moorish Science Temple of America,” in Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 41.

[95] Fauset, “Moorish Science Temple,” 42.

[96] Ibid., 47.

[97] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 11.

[98] Fauset, “Moorish Science Temple,” 41, 44.

[99] Ibid., 47.

[100] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 12–13.

[101] Knight, The Five Percenters, 23; Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 11.

[102] For excerpts of these referenced Lessons, see pages 1 and 10.

[103] Knight, The Five Percenters, 31.

[104] Ibid., 28.

[105] Genius. “Bring da Ruckus.” Accessed March 6, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-bring-da-ruckus-lyrics.

[106] Vanity Fair, “Wu-Tang’s RZA Breaks Down 10 Kung Fu Films He’s Sampled.” Last modified September 3, 2019. Video, 13:34. www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZ67KyHX-cY&list=LLkXio3_-CB7rVtYdUQX9h1A&index=4&t=0s.

[107] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 24; Vanity Fair, “RZA Breaks Down 10 Kung Fu Films.”

[108] Ibid. For the sake of space in this article, I also shorten the title of The 36th Chamber of Shaolin to The 36th Chamber.

[109] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 36.

[110] Ibid., 12.

[111] Vanity Fair, “RZA Breaks Down 10 Kung Fu Films.”

[112] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 59.

[113] Ibid. RZA also describes The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter as providing “the brotherhood, the soul.”

[114] Genius, “Bring da Ruckus.”

[115] Genius, “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’.”

[116] Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 24.

[117] Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 172.

[118] Hawkins, RAW, 35.

[119] Ibid.

[120] Ibid.

[121] Ibid.

[122] Genius, “Protect Ya Neck.”

[123] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 4–5, 8, 48.

[124] Genius, “Can It Be All So Simple / Intermission.”

[125] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, 130; Floyd-Thomas, “Jihad of Words,” 172.

[126] Ibid.

[127] Genius, “C.R.E.A.M.”

[128] See Figure 3.

[129] The RZA, The Wu-Tang Manual, iii.

[130] Ken McLeod, “Afro-Samurai: Techno-Orientalism and Contemporary Hip Hop,” in Popular Music 32, no. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 264. Accessed March 7, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/24736760.

[131] Vijay Prashad, “Orientalism,” in Keywords for American Cultural Studies, Second Edition, eds. Burgett Bruce and Hendler Glenn (New York: NYU Press, 2014), 188. Accessed March 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1287j69.52.

[132] Knight, The Five Percenters, 216.

[133] Ibid.

[134] Ibid., 182.

[135] The Nielsen Company, “2017 Music Year-End Report,” accessed May 4, 2019, www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2018/2017-music-us-year-end-report.html.

Bibliography

Albanese, Catherine L. Introduction to America: Religions and Religion, 2nd ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1992.

Alim, H. Samy. “A New Research Agenda: Exploring the Transglobal Hip Hop Umma.” In The Hip Hop and Religion Reader. Ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Alim, H. Samy. “Re-inventing Islam with Unique Modern Tones: Muslim Hip Hop Artists as Verbal Mujahidin.” In The Hip Hop and Religion Reader. Ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Brown, Ethan. Queens Reigns Supreme: Fat Cat, 50 Cent, and the Rise of the Hip-Hop Hustler. New York: Anchor Books, 2005.

Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

Coleman, Brian. Check the Technique: Liner Notes for Hip-Hop Junkies. New York: Villard Books, 2005.

Fauset, Arthur Huff. “Chapter V: Moorish Science Temple of America.” In Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. “The Five Percenters.” (BUFILE: 157-6-34, 1980).

Floyd-Thomas, Juan M. “A Jihad of Words: The Evolution of African American Islam and Contemporary Hip-Hop.” In The Hip Hop and Religion Reader. Ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Gates Jr., Henry Louis. “Part Sixteen: Cultural Integration 1969–1979.” In Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History 1513–2008. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Genius. “Bring da Ruckus.” Accessed March 6, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-bring-da-ruckus-lyrics.

Genius. “Can It Be All So Simple / Intermission.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-can-it-be-all-so-simple-intermission-lyrics.

Genius. “Clan in da Front.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-clan-in-da-front-lyrics.

Genius. “C.R.E.A.M.” Accessed March 6, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-cream-lyrics.

Genius. “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-da-mystery-of-chessboxin-lyrics.

Genius. “Method Man.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-method-man-lyrics.

Genius. “Protect Ya Neck.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-protect-ya-neck-lyrics.

Genius. “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin’ ta Fuck With.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-wu-tang-clan-aint-nuthing-ta-fuck-wit-lyrics.

Genius. “Wu-Tang: 7th Chamber.” Accessed February 14, 2020. genius.com/Wu-tang-clan-wu-tang-7th-chamber-lyrics.

Goldblatt, Mark. “Hip Hop’s Grim Undertones.” USA Today, October 29, 2002. usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/2002-10-29-oped-goldblatt_x.htm.

Hawkins, Lamont “U-God.” RAW: My Journey into the Wu-Tang. New York: Picador, 2018.

Kendrick Lamar. “Kendrick Lamar—‘i’ (Live on SNL).” Last modified November 16, 2014. Video, 4:51. www.youtube.com/watch?v=sop2V_MREEI.

Knight, Michael Muhammad. The Five Percenters: Islam, Hip Hop and the Gods of New York. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007.

McLeod, Ken. “Afro-Samurai: Techno-Orientalism and Contemporary Hip Hop.” Popular Music 32, no. 2 (2013): 259–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. Accessed March 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/24736760.

Miyakawa, Felicia. Five Percenter Rap: God Hop’s Music, Message, and Black Muslim Mission. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Nash, Kieran. “How Wu-Tang Clan Revolutionized Hip-Hop Forever.” BBC, April 26, 2019. www.bbc.com/culture/story/20190426-how-wu-tang-clan-revolutionised-hip-….

The Nation of Gods and Earths. “What We Teach.” The 5% Network. Modified January 1, 2005. web.archive.org/web/20050101085428/http://www.ibiblio.org/nge/.

The Nielsen Company. “2017 Music Year-End Report.” Accessed May 4, 2019. www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2018/2017-music-us-year-end-repo….

Patterson, Troy. “Four Shows at the Center of a Golden Age of Hip-Hop Television.” New Yorker, November 1, 2019. www.newyorker.com/culture/on-television/four-shows-at-the-center-of-a-g….

Perry, Imani. Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Prashad, Vijay. “Orientalism.” In Keywords for American Cultural Studies, Second Edition, ed. Burgett Bruce and Hendler Glenn. New York: NYU Press, 2014. Accessed March 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1287j69.52.

Rose, Tricia. The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop—and Why It Matters. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

The RZA. The Wu-Tang Manual. New York: The Penguin Group, 2005.

Sorett, Josef. “Believe Me, This Pimp Game Is Very Religious: Toward a Religious History of Hip Hop.” In The Hip Hop and Religion Reader, ed. Monica Miller and Anthony B. Pinn. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Vanity Fair. “Wu-Tang’s RZA Breaks Down 10 Kung Fu Films He’s Sampled.” Last modified September 3, 2019. Video, 13:34. www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZ67KyHX-cY&list=LLkXio3_-CB7rVtYdUQX9h1A&index….