Corinna Treitel is an associate professor of history and director of the medical humanities minor. Amy Pawl is a teaching professor of English and director of the children’s studies minor. Cassie Brand is curator of rare books in University Libraries.

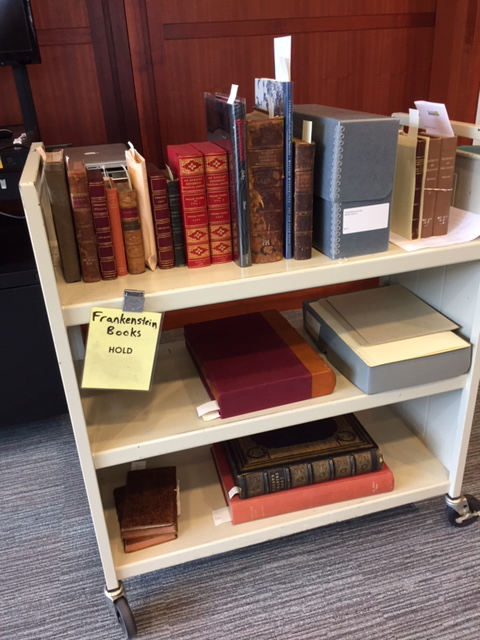

It takes an academic village to raise a monster – or, at least, a monster exhibit. Unlike the orphaned Creature at the center of Mary Shelley’s novel, this ambitious project had many dedicated progenitors. More than two years before the 200th anniversary of the original 1818 publication of Mary Shelley’s novel, planning began on events to mark the occasion. As part of a new interdisciplinary class devoted to Frankenstein, Corinna Treitel and Amy Pawl began conversations with Olin Library curators Garth Reese, Cassie Brand and Erin Sutherland about how the class could explore the resources of Special Collections, including an 1831 edition of Frankenstein, acquired specifically for the anniversary events.

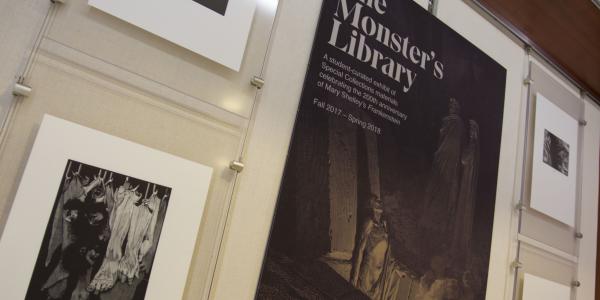

After multiple creative sessions (none of which involved lightning, unfortunately), a theme took shape: We would view the novel itself as a collection of three “libraries,” thus highlighting the extraordinary intertextuality of Shelley’s book. The exhibit title, The Monster’s Library, was suggested by incoming student Elliott Crosland, who drew his inspiration directly from one of the novel’s memorable images, freshly conceptualized for the exhibit: In volume two, Victor Frankenstein’s abandoned Creature finds a leather satchel in the woods, loaded with important books — effectively a small, portable (and influential) library. In addition, students identified two other libraries implied by the text, those of Victor Frankenstein and Mary Shelley herself.

As the semester started up, we moved from the planning phase to the discovery phase. While students read Frankenstein, we asked them to collaborate on a near-exhaustive list of all works quoted or referenced anywhere in the original text or introduction. Students made their entries (with analysis), on a course Wiki page. Thus when Victor Frankenstein flees from the scene of his creation, exclaiming that he is “Like one who on a lonesome road/Doth walk in fear and dread,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s contemporary Rime of the Ancient Mariner went up on the list. References to Agrippa and Paracelcus prompted students to investigate the works of these early alchemists, rounding out Victor Frankenstein’s “library” with the addition of philosophical and occult studies. Still others researched works not directly mentioned in the novel: Using Mary Shelley’s own reading list — recorded in her journal and accessible on the academic website Romantic Circles — they located such profoundly influential works as Vindication of the Rights of Woman (Wollstonecraft) and Political Justice (Godwin), written by her own parents. These formed the core of the Author’s Library section.

Once the class had generated a list of possibilities together, we asked each student to select three texts from the list and then write up a brief proposal introducing each one, explaining its significance in the exhibit, and confirming that the library system owned an interesting copy. The two instructors then reviewed the proposals, seeking to strike a balance between honoring students’ top choices and ensuring that each of the exhibits’ sections had adequate coverage and coherence. After this, the instructors mostly acted as orchestra conductors, engaging the students in iterative rounds of working individually and collectively to complete the project.

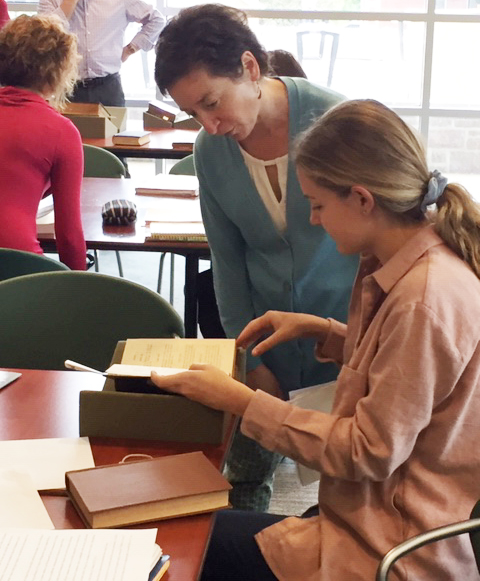

At last it was time for students to touch real books. During a special class held at the library, they “introduced” their text to other members of their group and began brainstorming how all the entries would cohere. During this library visit, we discussed how exhibits differ from academic papers, with instructions on how to be successful in this new form of writing. Students were asked to think about the visual aspects of the display: Would the book catch a viewer’s attention? Should the book be displayed closed or open? What page should be displayed? In exhibitions, the visual and the intellectual work together to inform and engage viewers. Not all books are visually interesting, which is where the exhibit text becomes even more important.

Exhibit labels are inherently short descriptions, and the students were asked to stay within a 60-word limit for their labels. Sixty words isn’t much, especially when there is so much interesting information to share. We helped students narrow the focus of their labels and choose one aspect of the book to write about. What did they want to teach other students, faculty, staff and casual visitors about Frankenstein? Which messages, key points or questions did they want to communicate? How would they accomplish their goals? From the beginning, we invited students to think of themselves as campus educators. The emphasis on the student as expert empowered students to write their labels with authority and confidence.

After students had written and posted short entries for their own text, we used class time to allow groups to generate brief introductions to their portion of the exhibit. Staff in Special Collections then put together a draft catalogue and invited editing. On the whole, the instructors decided that minimal editing was in order. Students, we noticed, had generated their best writing of the semester in these entries. In addition, we felt strongly that because this was a student-curated exhibit, students’ voices should lead.

At the end came the grand opening, when we got to see the exhibit mounted by staff according to the vision forged by the class. With no idea what to expect and plenty of refreshments to keep us going, we lingered with pleasure for viewing and conversation about what we had accomplished. Throughout the display period, Special Collections enjoyed a stream of visitors to the exhibit, which highlighted both the students’ work and the items held in Special Collections.

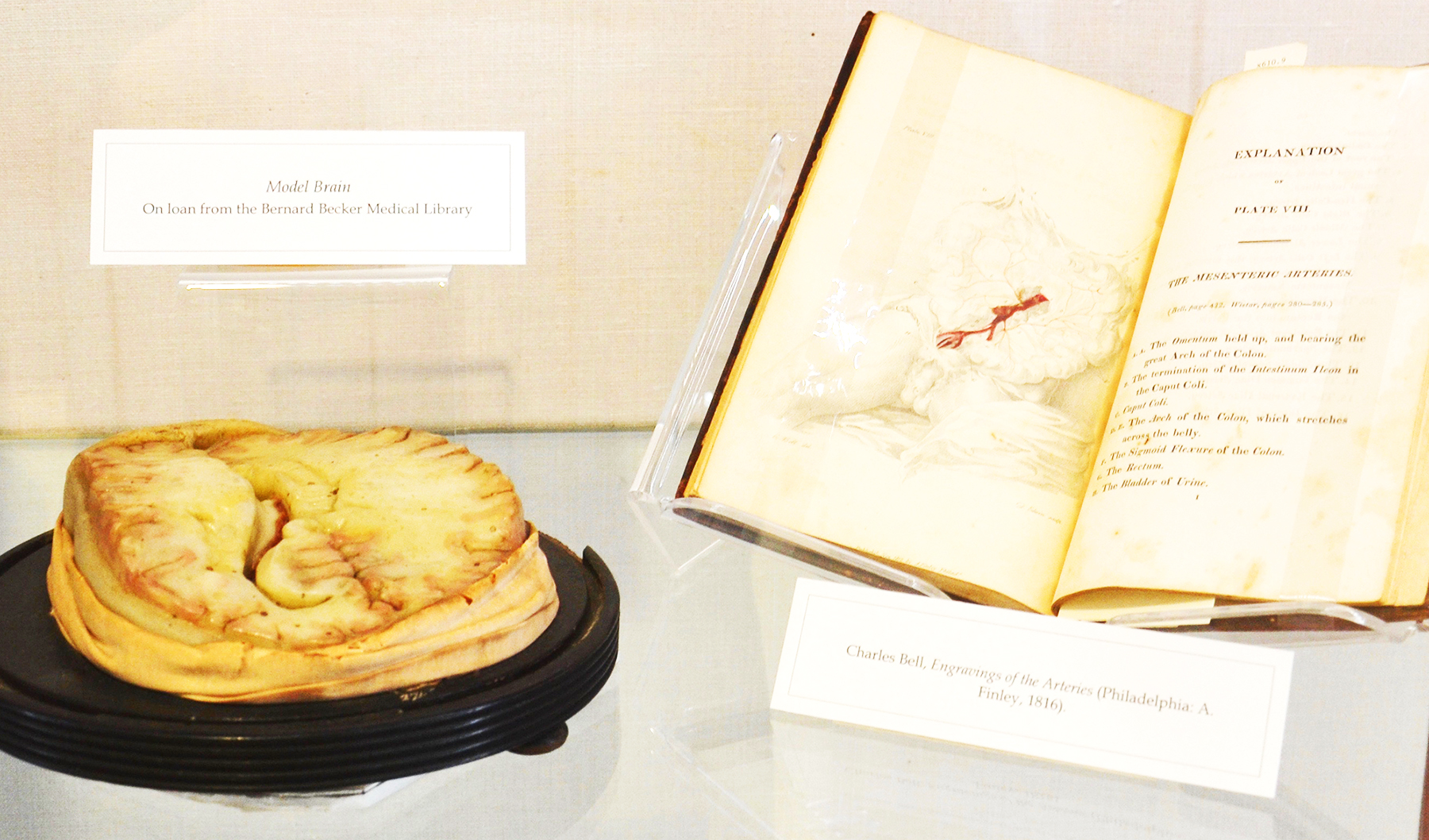

Students gave the library project high marks. Course evaluations made clear that students valued the combination of specializing in just one aspect of the novel’s literary history and working with others to assemble a picture that was larger than the sum of its parts. Several noted that the work they did on this project was the work of which they were most proud in college. These comments echoed our own observation during the semester that students connected with their chosen texts passionately. One student who had read Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther early in her college career took charge of locating a German original and explaining why a novel most people have never heard of ended up being so central to the drama of Frankenstein. Yet another with strong interests in both medicine and the humanities made sure that the experiments in medical galvanism, which probably inspired the novel’s famous creation scene, had a place in the exhibit. Two other students with an archival bent located letters from Mary Shelley and her husband Percy held in Special Collections and used these to illuminate the larger intellectual and social environment within which Frankenstein emerged.

For the staff and instructors who supervised this project, two major lessons stand out. First, students do their best writing when their audience is not the professor but the public. When students are put into the role of being “the expert” rather than “just another student” writing for an instructor who seems to know everything, they are able to inhabit the role seriously and well. In other words, knowing that their work would have a public audience as well as a permanent place in the historical record focused our students’ minds wonderfully. Second, students in humanities classes enjoy and benefit from collaborative work. Traditional assignments (e.g., critical readings, scholarly reviews, research papers) reproduce the model of individual scholarship that is the route to promotion in the humanities. Those assignments are and will continue to be valuable. Still, we wondered: What would happen if we took our lead from STEM fields, where collaborative intellectual experiences are the norm for everyone from a novice to a Nobel Prize winner? That’s the experiment we tried in The Monster’s Library and we judged it so successful that we repeated it again in 2018 with The Monster in the Library, an exhibit tracking Frankenstein’s afterlives in university collections. That experiment worked, too.

Editor’s note: The Monster’s Library was recognized with a notable citation as part of the Association of College and Research Libraries Rare Books and Manuscripts (RBMS) Section’s 2019 Katharine Kyes Leab and Daniel J. Leab American Book Prices Current Exhibition Awards. Check out the exhibition catalogue by following this link.