Abstract: In 1908, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated (AKA) was established for the educational and social uplift of Black women. Over a century later, now with more than 300,000 members, AKA persists as the largest and most global Black women’s organization in the world. Some research has been conducted by scholars like Deborah Whaley, Paula Giddings, Gregory Parks, and Clarenda Phillips on historically Black Greek-letter sororities (BGLS). However, their work focuses on the sociopolitical and historical legacies of these organizations. Distinctly, this project privileges the everyday embodiments of members within AKA as unique sites of knowledge production for research on Black sisterhood and Black womanhood. Specifically, I utilize mixed ethnographic methods of participant observation, semi-structured interviewing, and oral history to investigate how the Ivy Leaf, heeled footwear, and walking are key aspects to developing the Alpha Kappa Alpha identity. I argue that the Ivy Leaf—importantly, its connections to mobility and stature—is essential to an AKA rite of passage that transforms candidates into both members of AKA and Black women with the physical and mental resilience to face a racialized and gendered world.

Introduction

Ladies, you all need to walk on one accord! I should only hear one foot hitting the ground after another. One line! One sound! [1] Ceaselessly, the Membership Intake Chairman repeats this mantra to the new co-initiates [2] of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated (AKA). Co-initiates begin the Membership Intake Process (MIP) [3] as individuals, but over time these eager young women learn to operate together as an impenetrable unit. The first step of this unifying process is their walk. As they practice this rhythmic cadence, they don classic business pumps that are just shy of stilettos. The heel is just high enough to produce a mild level of discomfort for the co-initiate unaccustomed to arching her feet in that fashion. Day by day, co-initiates learn to make this walk feel natural. By the time final Sunday arrives, when they gain full rights and privileges as members of AKA, they no longer must ruminate over which foot to place down where and when. By the end of their MIP, co-initiates have learned how to walk like an AKA.

In this article, I discuss some of the most overlooked, yet illuminating elements of identity, solidarity, and sisterhood within AKA—our feet. I am beginning from the ground-up to place emphasis on the foundation for which Alpha Kappa Alpha women are built. While our Ivies [4] remain steadfast and strong throughout life’s invariable challenges, this resilience is cultivated only through sturdy roots in fertile soil. This article focuses on these resilient roots, specifically how foot placement, heeled footwear, and mobility are key aspects to developing the Alpha Kappa Alpha identity. I argue that the Ivy Leaf—importantly, its connections to mobility and stature—is essential to an AKA rite of passage. Specifically, this rite of passage transforms candidates into both members of AKA and Black women with the physical and mental resilience to face a racialized and gendered world. This marked emphasis on able-bodied-ness—during historical and contemporary pledge processes—forces women with disabilities to forge alternative modes of completing the ritual process and, in turn, negotiating their identities within AKA.

To appropriately tackle all my research questions, I conducted an ethnography—an anthropological research method that emphasizes the use of qualitative measures to collect rich data on a selected population of individuals. This ethnography was informed by feminist principles that pay considerable attention to power dynamics between researcher and contributors, interpretations of data collected, and unique sites of information (Buch & Staller 2007). Guided by feminist principles, I used mixed ethnographic methods that include participant-observation and semi-structured interviews. In employing these various techniques to identify and collect data, as well as in utilizing a feminist epistemological framework, I gain insight into “the contexts of women’s lives, the ways in which women experience and resist gender norms and the ways in which difference is organized across lines of gender, race, class, and sexuality” (Buch & Staller 2007, 194).

Initially, many of my research questions were guided by a desire to understand the literal phenomena that occur in historically Black Greek-letter sororities. Why are certain behaviors and mannerisms regulated in specific ways within the larger organization, and how do these actions embody an understood group identity? The best ethnographic method to tackle these questions on individual and group identity performance is participant-observation—"intensive involvement with a group of people over an extended period of time” (Davis & Craven 2016, 85). As a native ethnographer, someone who is a member of a historically Black Greek-letter sorority and, thus, “conduct[s] their research in familiar settings,” I observed AKA’s public programming, e.g., new member presentations, to collect detailed ethnographic fieldnotes for my project (Buch & Staller 2007, 189). I used these observations not only to help locate further points to probe in in-depth personal interviews and oral histories, but also to provide greater context for understanding the influence of BGLSs on their members.

While participant-observation is helpful for setting the stage of historically Black Greek-letter sororities, semi-structured interviews are more appropriate to tackle members’ specific experiences within AKA as well as how these experiences construct their identity. Particularly, these ethnographic interviews provided the proper space to engage with research questions on how Black women of marginal identities factor into a largely uniform sisterhood framework. In what kinds of spaces within the organization do these members feel that their identities are most salient?

These ethnographic interviews were “open-ended … in the sense that they frequently departed from predetermined questions to get more information using probes” (Davis & Craven 2016, 86). In addition, these interviews were “semi-structured” such that these interactions were conducted with a “specific interview guide—a list of written questions that I need[ed] to cover within a particular interview” (Hesse-Biber 2007, 115). Many of these semi-structured interviews began with the following questions:

- In what spaces do you feel most pride being an AKA?

- How would you define Black sisterhood? In what ways does AKA cultivate this?

- How would you define Black womanhood? Was this definition influenced by becoming an AKA?

As data collection progressed, however, I adapted my questions to address interesting themes that continued to emerge from my contributors’ responses. By maintaining a set of questions that I asked all contributors—questions that were each open-ended enough to allow for “spontaneity on the part of the researcher and interviewee”—my ethnographic interviews had anchoring points so that I could effectively compare the diverse sets of experiences (Hesse-Biber 2007, 115). However, in adapting my questions across individuals, time, and space, my conversations homed in on phenomena that were both fascinating and particularly relevant to my contributors.

Moreover, I employed John L. Jackson’s technique of “calculated dimness,” which involves withholding information about one’s knowledge regarding an issue or subject so as to “avoid conjecture, acquire thorough information from subjects and attend to their circumstances, even at the risk of being considered an idiot” (Munem 2013). As a knowledgeable insider of these organizations, I did not want my own expectations or biases regarding certain questions to sway my contributors from providing an otherwise uninhibited and noncoercive personal narrative. I further utilized other feminist ethnographic interviewing techniques that allowed me not only to capture the words my contributors used to describe their experiences, “but also the spaces between the words, the meanings, the process of meaning-making, the emotion, and even the silence” (Leavy 2007, 158). I paid considerable attention to this silence as it provided “insight into her struggles and conflicts” as well as “indicate[d] that the categories and concepts we have available to interpret and explain our life experiences do not in fact reflect the full range of experiences out there” (Leavy 2007, 159).

My status as an insider within Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated more broadly grants me access to sites of historically Black Greek life; however, relations to members of other chapters across the country grant me both entrance and acceptance into communities of which I am not immediately a part. As a feminist employing ethnographic methods, I “blend with the people and the social context of the research [to] … access the depth of meanings required for adequate and trustworthy qualitative research” (Leavy 2007, 150). While it is important to have an entry point into the field, my deep enmeshment within Alpha Kappa Alpha could have potentially created issues. I did not want to tarnish the close-knit relationships I have with other members, and I did not want to damage the brand [5] of the organization in any way. I paid considerable attention to how I gathered data, ensuring that the lines between myself as a member and as a researcher did not become blurred throughout this process. Further, I ensured that my interpretations of the data were true to the contributors’ original intentions and experiences by allowing my contributors to provide feedback on these interpretations throughout the process. As a member of AKA, I did not want my own biases to impact the ways in which I interpreted the data. By engaging in a process which continuously involved my contributors, I hoped to eliminate any influence of my own beliefs on the data and the final product.

Strong, Resilient Ivies

“The challenge for Hedgeman’s committee has been to come up with a symbol that projects strength and endurance. ‘Those few girls [the nine] felt that they had something born within them that they wished to nurture and have grow.’ Hedgeman offers a green enameled ivy leaf, with the Greek symbols AKA engraved in gold in each leaf. The fit is undeniable, and the vote is unanimous.” —McNealey 2006, 22

AKA is defined by the Ivy Leaf. This tenacious, evergreen plant maintains a youthful quality despite acerbic weather conditions and decaying surroundings. It is the symbol of eternal life. Founders like Ethel Hedgeman [6] sought after an emblem that could exemplify a steadfast resiliency against sociopolitical oppression facing Black women of the early twentieth century. The Ivy Leaf could propel them toward a life that they had often imagined but was just out of their reach. The Ivy Leaf could instill strength and fortitude in members to come.

Later generations of AKA invoked the notion of the Ivy for a variety of purposes. In the early years, prospective individuals were required to join an Ivy Leaf Pledge Club as a prerequisite for admission into the sorority. Black attorney Lawrence Otis Graham relays his aunt’s experience in the Ivy Leaf Pledge Club:

We had to learn a lot more about the historic beginnings of the AKAs, and we did it by writing long letters of application to the Ivy Leaf Pledge Club—the senior wing of the sorority that regulated the admissions process—and then attending monthly meetings where the older students tutored us on the history (Graham 1999, 96).

These Ivy Leaf Pledge Clubs were a way of lengthening the process of membership for interested individuals while simultaneously instilling determination and resolve for young women about to embark on a rigorous endeavor. With early introductions to the Ivy Leaf, candidates quickly learned what it meant to become trendsetters and visionaries. They learned that it meant to become an AKA.

Figure 1. The official Ivy Leaf symbol of AKA

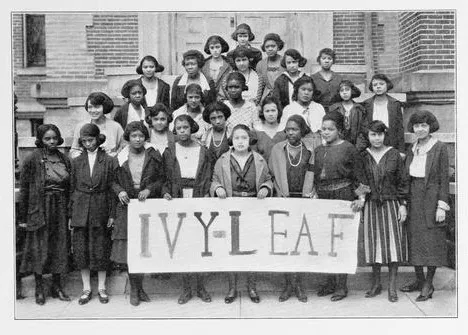

Figure 2. The Ivy Leaf Pledge Club at Wilberforce University in 1922.

Throughout the years, chapters have done away with these pledge clubs, and the Ivy Leaf symbol was transformed into a title for young women who were pledging AKA. Many of my contributors who were initiated before 1990—the year when pledging and hazing were publicly denounced by AKA and other BGLOs [7]—mentioned being referred to as Ivies while they pledged. Linda, who joined the sorority in 1953 at a Southern HBCU, offhandedly explained to me these symbolic designations.

Linda: And we embroidered ivies on the socks because we were known as Ivies at the time. We would go to the dining hall, and we had a special table to sit. [8]

For Linda, pledging operated “above ground,” meaning that pledge activities occurred during a college-sanctioned time frame where the public could observe. Though AKA was the first BGLS to make it onto the collegiate scene, other BGLSs sprung up in the years following. [9] To signify themselves as Ivies, Linda and her line sisters were tasked to adorn their socks with the symbol. Aesthetic choices [10] like this were vital for sororities like AKA to distinguish themselves from their Black Greek counterparts, especially at an HBCU in the 1950s.

(Ivy) Standing in Heels

In a modern context, where acts of pledging and hazing are outlawed within AKA, the concept of the Ivy has transformed into the Ivy Stance. Largely done in public displays like New Member Presentations and Stroll Offs, the Ivy Stance is the phrase given for how twenty-first-century women of AKA must stand. Generally, the Ivy Stance involves a person’s head tilted back, shoulders pressed together, spine elongated, arms pressed to the sides, palms facing parallel to the ground, and feet in third ballet position. By no means is the Ivy Stance a comfortable position. Especially during these public performances, the stance is often held for extended periods at a time without pause. The Ivy Stance demands focus and mental resolve. One wandering thought could potentially allow a Soror to lose her balance, sending her toppling.

The Ivy Stance is complicated by the fact that heels must be worn. Contemporary AKA documents on protocol specify heeled footwear in three dimensions: type, height, and color. While there are a variety of heeled shoe options, the ones most appropriate for AKA procedures are the following close-toed varieties: the kitten, pump, and ballroom heel types. Kitten heels are a shorter variety of stilettos with heel height typically around one inch. They were introduced during the mid-twentieth century for young adolescents who could not walk in higher heels (“Kitten Heel” 2019). The pump is a higher heel, typically around three inches in height, that was popularized in the U.S. during World War II as a result of soldier’s fascinations with pin-up girl posters. Importantly, this shoe type began to create meaningful associations between heel height and physical attractiveness of women. Finally, ballroom heels are strappy shoes, typically around two inches in height, with a sturdy heel designed for various dance techniques (“High-Heeled Shoe” 2020).

Figure 3. An image from a fall 2017 New Member Presentation of a Midwest AKA chapter where members stood in Ivy Stance.

Categories of footwear assessment—heel height, type, and accessories—are often violated by newer members who confuse appropriate heel types with their inappropriate counterparts. Tracy, a member in her 50s from a Midwest graduate chapter, spoke to me about this phenomenon during a private stroll practice.

Tracy: Have you all told these girls what a business heel is? I am seeing some girls wearing a kitten heel while others got on stilettos. And to make things worse, most of them can’t even walk in their shoes. They need to know that those shoes are not appropriate. And, I mean, have they ever heard of breaking a shoe in?

As Tracy suggests in her comments, heel height is one of the leading criteria often misunderstood by new members. Unlike the 1950s, when kitten heels were explicitly created for the use of adolescent women, younger AKAs of the 21st century are expected to wear higher heels than their older counterparts. Kitten heels are exclusively reserved for Golden and Diamond members [11] whose mobility has begun to decline. On the other extreme, stilettos are viewed as immodest and hypersexual—a shoe that is unbecoming of the behaviors and attributes of an AKA. It becomes the job of the undergraduate member to discern a podiatric politic that does not waver on either of these extremes.

Black women have always needed to be “savvy cultural negotiators” with regard to their aesthetic decisions (Gimlin 2002, 106). U.S. ideals of beauty have always structurally excluded Black women from a dominant model of femininity. In the lens of most contemporary and historical beauty regimes, Black women are viewed as racialized others capable of womanhood but not femininity (Craig 2002). High-heeled footwear, however, allowed Black women to reconfigure their identities within a dominating, Eurocentric model of aesthetics. The business pump connotes professionalism, class, and femininity for its wearer. Many of my respondents alluded to the ways that AKAs are often marked by “the way they carry themselves.” [12] Indeed, this idiomatic phrase suggests something figurative about the way individuals might conduct themselves in a space. However, I theorize that by donning business pumps, women of AKA literally carry themselves differently. By wearing heeled footwear, Black women are consciously raising their positions within beauty regimes from devalued to valued (Gimlin 2002).

In the short term, heel wearing fortifies the foot through calluses. However, in the long term, the morphology of the foot arch can alter from sustained heel-wearing. Heel wearing is a form of Debra Gimlin’s “body work” that Black women undergo “to repair the flawed identities that imperfect bodies symbolize” (Gimlin 2002, 5). At the turn of the twentieth century, the ideal of femininity in the United States was most accurately depicted by the Gibson Girl—an image of a slender and tall woman with a voluptuous bust and wide hip (“Gibson Girl,” 2019). While feminine ideals have certainly altered over the last century, this feminine ideal of physical attractiveness has made a resurgence through the popularization of modern figures like Kim Kardashian and Beyoncé. Not only does heel wearing allow Black women to appear taller, raising their statures to mirror a sought-after aesthetic, but also the demands of wearing a heel work to lift the rear and accentuate the legs. Advances have been made over the last century regarding the sociopolitical position of Black women. Yet the work is far from done. In a contemporary sociopolitical moment, women of AKA continue this body work to negotiate their identities within a public arena, a continuous process that is iterative across time and space.

Ivies March On (and Off) the Yard

Beyond standing in high heels, walking is an important element to the AKA identity. In the previous section, Tracy wondered whether the stumbling co-initiates had “ever heard of breaking a shoe in.” [13] The phrase “breaking in a shoe” refers to walking around in a new pair of shoes to familiarize and acclimate the foot to the rigid footwear. In undergoing this process, individuals build up their tolerance for wearing an initially uncomfortable shoe over longer periods of time through shorter stints of trial walks. Importantly, Tracy’s comment shifts us to thinking about the role that walking plays in the sociopolitical and historical legacy of AKA. I theorize that the notion of breaking in a shoe maintains relevance for older and younger generations of AKA to develop stamina for a world where their identities are triply oppressed. To begin a discussion on walking, I turn to a consideration of dominant BGLO culture on college campuses during the mid- to late twentieth century.

Prior to 1990, pledging was a defining part of becoming a member of AKA. Colleges worked with BGLOs to standardize pledge processes during specific times of the year. Within AKA, the pledge process began with admission into the Ivy Leaf Pledge Club (ILPC). Along with learning the history of AKA, members of the ILPC took part in a university-sanctioned letter-writing period—a time when AKA hopefuls wrote letters to current members of the chapter. Madge, a member in her 50s who joined in 1983 at a Southern HBCU, described to me the content of her letters.

Madge: Hi! How are you doing, so and so? I hope you are enjoying your summer! Are you at home? You would tell about what you were doing, kind of just introducing yourself to them. I remember only two of them wrote me back. I remember their names to this day, the only two who wrote me back. [14]

Indeed, this letter writing took place before the advent of personal computers. In my conversation with Lisa—a member in her 50s who joined in 1985 at another Southern HBCU—she jokingly recalled having to use a typewriter, restarting her letter from the beginning each time an error was made. [15] A tedious process, letter writing was one way that current members asserted their power over potential candidates of AKA. Letter writing placed prospective members in a position where they began to “experience what it is like to be low,” instantiating current members’ dominance over prospective members and initiating an early step in Victor Turner’s classic rite of passage (Turner 1969, 97).

Additionally, current members of the chapter asserted their authority over candidates—and, effectively, engaged them in a process of pre-pledging [16]—through visits. Visiting required AKA hopefuls to walk to the homes of Sorors on and off campus and introduce themselves to current members of the chapter. Visiting was a necessary part of pre-pledging. If a prospective candidate did not visit enough members within the chapter, they were denied entrance into the sorority. These visits often came with a variety of challenges:

Madge: You used to have to visit. You would have to find out who was in [the apartment], where they live … You would go visit, and you were told always take a notebook. They would give you assignments when you would do visits. I remember this girl had a little teddy bear—a big teddy bear holding a little teddy bear. Her teddy bears’ names were Sugar and Spice (her boyfriend had given it to her). I [was] also told not to go by [my]self because you could kind of get [mixed up]. But somehow, I was there by myself. She was nice. [But then she goes], What about my bears? And I said, Oh, yeah. Your bears? Your boyfriend Calvin gave them to you. And she said, Which one is Sugar, and which one is Spice? I didn’t know. And she said, Don’t guess. If you don’t know, just find out and you can come back and tell me. And I said, OK. The visiting was interesting because if you were foolish enough to go by yourself, they would get on the phone and call all the other [Sorors], and you could really get put on a trip. You didn’t go visiting until you knew the person’s name (first and last), where they were from, what their major was, when they pledged, what was the name of their line, and their [line] number. That was baseline data. You didn’t go to visit anybody without knowing that information. [17]

In heels, young women might walk as far as two miles off campus to visit current members in the chapter. An anxiety-ridden endeavor, visiting required individuals like Madge to be resourceful enough to locate all “the baseline data” and resilient enough to withstand seemingly impossible queries.

Visiting also required leaving the familiar campus environment for places that were foreign to the prospective member (e.g., an off-campus apartment). During the visiting period, prospective members took part in Turner’s first phase of rites of passage: separation. This initial phase is marked by “symbolic behavior signifying the detachment of the individual or group either from an earlier fixed point in the social structure, from a set of cultural conditions (a ‘state’), or from both” (Turner 1969, 94). For these candidates, the social structure was the life on an HBCU campus (during the 1980s for Madge and Lisa, in particular). These trips disrupted the typical routine of a college student, limiting (and dictating) how their free time was spent outside of studies. Visiting involved movement across the boundaries of the campus to the broader community. Importantly, the mechanism by which this movement occurred was walking.

Eventually, candidates graduated (in a sense) from the Ivy Leaf Pledge Club and could apply for admission into the sorority. For those who were selected to be “on line,” [18] they began what the college understood as the official pledge process. As Linda mention in her anecdote on embroidered socks, pledges of AKA were collectively given the title Ivies. While there were many ways that Ivies could be identified, [19] they largely demonstrated their unity through their walking patterns.

Madge: I knew that my family members were in sororities and fraternities, but I didn’t really understand the way they maneuvered on the campus. And I remembered that we walked on an open line. I remember, I would see the Ivies. It was the first line I saw. It was twelve of them. [20]

As one might infer from the phrase that pledges were “on line” together, Ivies literally walked in a line across the campus. Whether it was to the cafeteria hall in the mornings [21] or to the library in the evenings, [22] Ivies marched in a single-file line everywhere they went.

Not only did Ivies walk in line across the campus, they also marched in unison. Like a military unit marching in time, Ivies' were synchronized in foot placement, spacing, and timing. If the Ace [23] placed her right foot down, every Ivy behind her placed their right foot down in that same instant. The Ace set the pace. It was the job of every pledge following her to anticipate her next step (or pause). Ivies were required to walk in step such that an outsider could close their eyes and hear only one pair of heels hitting the ground rather than twenty. Additionally, there needed to be close, equivalent spacing between pledges as they walked. It needed to be tight enough that a Pyramid [24] could not barrel through but spaced enough so that Ivies were not stepping on each other’s heels. If Ivies allowed their line to be “broken,” this suggested that there were chinks in their collective armor—a protection that was paramount to navigating the world of BGLOs specifically as well as a dominating White patriarchal world more broadly. The walk taught Ivies the importance of leaning on one another against classed, raced, and gendered oppressions (Collins 2002).

This level of precision is nothing short of spectacular. A group of individuals transforms into a unified collective, “ground down to [the] uniform condition” of an Ivy (Turner 1969, 95). The feat is even more complicated by the fact that Sorors routinely instituted additional guidelines for the Ivies’ walk.

Madge: Yeah, when [the Sorors] skee wee’d, [25] we had to skip. I remember, you might see a Pyramid slowly strolling around the campus … But Ivies are what?! Snappy, Big Sister! [26] Snappy, Big Sister! That’s why Portia’s line name is Curad because she was skipping, and her feet got twisted up and she fell. Oh, she fell several times! That’s why her line name was Curad: The Ouchless One. [27]

Requiring pledges to skip every time a Soror skee wee’d was a way to remind, Ivies of their lowly positions in the social structure of AKA. “The ordeals and humiliations, often of a grossly physiological character, to which neophytes are submitted represent partly a destruction of the previous status and partly a tempering of their essence in order to prepare them to cope with their new responsibilities and restrain them in advance from abusing their new privileges.” (Turner 1969, 103). With Ivies like Portia skipping a beat in the literal sense of falling, notions of individual achievement and high status dissipated. Ivies were required to view themselves as dependent upon each other. Due to the proximity with which they marched, if one person fell, it affected the line in its entirety.

Visibility was central to the Ivies’ march. It was not simply that Ivies walked in a line across the yard, [28] but rather that their march could be seen by a broader public. As “public intellectuals” who were invested in the “general social condition of the race and the possibilities of social improvement,” AKAs were tasked to be visible in the public sphere fighting for the advancement of Black people (Cooper 2017, 17). Jada, a politically active member in her 50s who pledged at a Southern HBCU in 1985, alludes to the impetus of civil rights for members of AKA.

Jada: We were protesting apartheid because that’s when apartheid was happening … We did the march on Washington and that was [with] the city-wide AKAs … We went to D.C., and we marched in the parade for Martin Luther King’s birthday. I mean, Stevie Wonder was there. It was amazing how many people were there. They were within [arm’s reach]. [29]

The stamina required to complete a rigorous pledge process—much of it cultivated through an emphasis on walking—translated to a life as members at the cusp of a social revolution. Sorors had developed the mental resolve to withstand setbacks ranging from harsh weather conditions to arrest by the local police. [30] Ivies walked across the yard so that Sorors could march for their communities.

Ivies (Who Cannot) Stroll

While pledging—and its associated activities like walking in line across a college campus—is banned in the contemporary AKA model, connections between walking and visibility persist through “strolling.” Otherwise known as party walking, strolling is an exclusively BGLO phenomenon where members move forward in a line while executing a series of dance motions and steps. It requires the careful combination of music, stepping, and stylization of each BGLO. Importantly, strolling, as opposed to stepping, [31] is a more contemporary feature to BGLO culture–one that I theorize developed from the Ivy march in a modern time where forging space and negotiating identity remain vital for Black students on college campuses where they have been historically excluded.

Strolling is a way that marginalized individuals can garner social capital during the undergraduate experience. Alice, a member in her 20s who joined at a Midwest chapter of AKA in 2017, alluded to the importance of strolling in our conversation.

Alice: Going to stroll practice and things for parties, that was fun … The thing with undergrad, there comes a certain amount of social clout that people want to get, or expect to have, with strolling, being seen. [32]

Alice is a Black woman who attends a predominantly White institution (PWI). She explained that as a minority subject, her identities are often overlooked in the eyes of the University. However, strolling allows individuals to construct spaces of Black collectivity within a White environment. Strolling is disruptive. The spontaneous eruption of synchronized step and dance—coupled with the bright color combination of salmon pink and apple green—begs the attention of a University public. Through strolling, Alice and other AKAs render themselves visible to a PWI as well as creating spaces where Black students feel a sense of belonging and pride.

Up until this point, I have focused on the experiences of able-bodied Sorors—those who can walk, march, and stroll. Indeed, the Original Nine [33]—in their collegiate days—were all able-bodied women. Sacred rituals that pertain to initiation and Ivy Beyond the Wall [34] ceremonies, for example, demonstrate how the organization designs sorority rites of passage around bodies with a certain degree of mobility. Membership, however, is not contingent upon being able to party walk or Ivy stand: “Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated does not discriminate in its membership selection practices on the basis of race, color, age, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, creed, marital status or disability” (“Prospective Members” 2020). Particularly in the twenty-first century, young women join AKA from a variety of backgrounds and life experiences. How do these members “develop an intense comradeship and egalitarianism” with their co-initiates when they do not undergo the collective toils of marching across a college campus or of learning a complicated stroll routine (Turner 1969, 359)?

Over the course of collecting this research, I was introduced to Lucy—a newly initiated Soror in her 20s with a rare genetic disorder. Her condition is characterized by abnormal skeletal development of the spine that greatly decreases her mobility without some external assistance (i.e., a wheelchair or golf cart). She utilizes a motorized wheelchair to maneuver around her environments, one of which is a densely populated HBCU in the South. After hearing about the project, one of my contributors invited me to attend a New Member Presentation where Lucy was one of 58 co-initiates being welcomed into AKAland. Fortunately, I was able to be in town to witness the presentation in person.

The show was nothing short of spectacular. A long line of girls in coordinating pink dresses and green masks marched onto the main floor of a packed University arena. The room was teeming with excitement, adulation, and, of course, piercing skee wees. From the precision of their walk to the crispness of their transitions—oftentimes, in and out of Ivy Stance—it became evident from the onset that this presentation was one to be remembered. The chapter had found a way to utilize the respective strengths of co-initiates to construct a performance that was innovative yet classic, a testament to both the chapter’s and AKA’s respective legacies. While there were many captivating theatrics throughout the show, one of the most fascinating elements was how the chapter found ways to locate Lucy’s identities in an environment that seemed to over-emphasize embodied-ness and mobility.

As the co-initiates marched one-by-one onto the main floor, Lucy rolled at a similar pace beside them. When the main line stopped, Lucy halted. Her coordination of the motorized device was impeccable. It appeared that she could anticipate when the line would stop or start their procession, when they might turn toward or away from the crowd. With each movement the line made, so too Lucy maneuvered in similar fashion. I was impressed by how seamlessly each transition was executed with an overwhelming sense of ease and confidence.

After the show, I learned from the Graduate Advisor [35] that not only was Lucy keeping up in pace with the line, but also that she was keeping up in place with her position in the line. During the “reveal” [36] portion of the evening, audiences learned that she was the Deuce—a coveted title referring to the second person on the line. In this emotional moment, Lucy was given the opportunity to speak directly to the audience:

Lucy: My … name … is … [Lucy]! I am from a city where all of [the chapter] will neverrrr forget—Douglasville, Georgia. I am the deuce of this line! And my sorors will foreverrrr call me … they will foreverrrrrrrrrr call me, God speed!

Lucy dragged out the last phrase, emphasizing the notion that she would always be called in to AKAland—that her identity had become sutured to Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated. “The ritual subject, individual or corporate, is in a relatively stable state once more and, by virtue of this, has rights and obligations vis-à-vis others of a clearly defined and ‘structural’ type” (Turner 1969, 94). To combat the notion of invisibility that often gets placed upon Black disabled bodies—particularly, within the inaccessible environments of college campuses—Lucy utilized AKA as a means of instantiating her identity within both the sorority and the larger University.

Conclusion

The Ivy Leaf, heeled footwear, and walking are three elements paramount to the way that AKAs cultivate and maintain collective identity. Through the Ivy Leaf, Sorors are challenged to develop characteristics of strength and endurance paramount for both completing service as AKAs and existing in a highly racialized and gendered society. While it began as a symbol to cultivate unity amongst members, the Ivy Leaf has expanded to represent both progress within the sorority and identity transformation. Importantly, this AKA rite of passage—from candidate to pledge to member—occurs through a marked emphasis on walking and mobility. Collective movement, particularly while donning harsh footwear, further reifies the notion of unity and mutual cause amongst members. It is through walking that Sorors learn how to depend on and develop trust in one another—factors that are paramount to lifelong sisterhood. It is also through walking that Sorors become public leaders on issues affecting their campus communities and beyond.

On the other hand, an emphasis on heeled footwear and mobility limits the incorporation of disabled individuals into an authentic sisterhood. Sorors who do not undergo a rite of passage—one that incorporates collective movement—must construct alternative methods to complete the ritual process and generate a sense of collectivity with newly initiated members. For Lucy, this looks like maneuvering alongside her Sorors in ways that mimic and complement their movements, but also diverge in ways that are unique to her condition. Lucy must navigate her identities within the sorority in ways that her newfound Sorors may never understand. In one of her Instagram posts, however, Lucy commented on her commitment to creating space for her identity—and identities like hers—within AKA:

Lucy: November 24th, 2019 an Alpha Kappa Alpha woman was born. I’ve prayed and fasted for this moment. Faith without work is dead. It’s been a long time coming but they finally freed the deuce! The Sweet [Chapter Name] will forever be embedded in me. I just want to be an inspiration to others. I didn’t let ANYTHING stop me from pursuing my dreams! Let me inspire you to go chase your dreams. Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. and Sweet [Chapter Name], I hope y’all are ready to go to the next level quick and in [a] hurry because “God Speed” has been born and I’m ready to get the ball rolling!

Like the founders, Lucy is a trailblazer in her own right, paving the way for more inclusivity and belonging within AKA. For her, this looks like being one of the first undergraduates to undergo a highly embodied membership intake process while seated in a wheelchair. Indeed, Lucy’s methods of integrating herself within the sisterhood will diverge from individuals who follow her.

In my own experience, these assumptions that surround the ability status of largely undergraduate members extend beyond what is visible. I am a 22-year-old Black woman who suffers from chronic back and tailbone pain. Some of my younger contributors shared with me their physical impairments ranging from scoliosis to carpal tunnel to plantar fasciitis. Frequently, we have discussed how our conditions have impacted our experiences within the sorority. AKA must recognize that ability is a temporary condition for all its members as well as learn to expand certain sorority practices to include individuals of all (dis)abled backgrounds. While this process can begin with footwear and walking, it must extend beyond those activities to create more just and equitable spaces for all its members.

Endnotes

[1] More colloquially known as the Dean of Pledges or DP, the Membership Intake Chairman is responsible for imparting the knowledge and wisdom of AKA to new members and executing the full Membership Intake Process.

[2] Co-initiates refers to individuals who underwent a Membership Intake Process (MIP) together. Historically, they are often referred to as pledges. However, I refrain from using the term pledges for its connections to a history of hazing. Later in this chapter, I utilize the term pledges because I am both referring to an era when that term was routinely used without negative connotations as well as referring to conversations with older contributors who still use that term.

[3] This refers to the official, standardized process of becoming a member of AKA. This process was carefully developed by the governing body of the Sorority in recent years to decrease the potential for discrimination and hazing in chapters across region and time.

[4] This is the official symbol/plant of AKA. A three-leafed plant, the Ivy represents strength, endurance, and vitality for members.

[5] Safeguarding the brand is something that members of AKA are taught upon their entrance into the organization. As members, our personal behaviors can easily be interpreted as representative of the larger organization and its ideals. It is for this reason that members are urged to maintain a positive and productive self-image—engaging in behaviors that do not reflect poorly upon AKA—to ensure the longevity of AKA.

[6] There were nine original founders of AKA: Ethel Hedgeman, Anna Easter Brown, Beulah E. Burke, Lillie Burke, Marjorie Hill, Margaret Flagg, Lavinia Norman, Lucy Diggs Slowe, and Marie Woolfolk.

[7] This ban was instituted as a direct response to incidents of hazing that occurred in each organization’s history. Due to the controversy this ban sparked, it was discussed heavily in newspaper media: Barbara Bradley, “A Pledge of Change from Alpha to Omega; Blacks Worry Greek Reforms May Go Too Far,” The Commercial Appeal, November 15, 1990; Michelle Collison, “8 Fraternities and Sororities Announce an End to Hazing, The Washington Post, February 19, 1990; Michel Marriott, “Black Fraternities and Sororities End a Tradition,” The New York Times, October 3, 1990, B8; David Mills, “Fraternity Violence: The Pledging Debate: The Greeks: There Is a Move Afoot to Do Away with Hazing and the Traditionalists Are Outraged and Vow to Fight,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1990; David Mills, “The Wrongs of the Rites of Brotherhood; Leaders of Black Fraternities Move to End a Cruel Tradition of Violent Hazing,” The Washington Post, June 18, 1990, B1, B6.

[8] This was excerpted from my oral history with Linda.

[9] Delta Sigma Theta, Zeta Phi Beta, and Sigma Gamma Rho were founded in 1913, 1920, and 1922, respectively.

[10] In another work, I discuss in greater detail the marked emphases on maintaining and manufacturing a certain appearance within AKA.

[11] These members have been a part of the organization for at least 50 and 75 years, respectively.

[12] This was explicitly stated in my interviews with Madge and Cynthia.

[13] This was excerpted from an interview with Tracy.

[14] This was excerpted from an oral history with Madge.

[15] This was paraphrased from an interview with Lisa.

[16] This refers to pledging activities that took place before the college-sanctioned pledge period.

[17] This was excerpted from oral history with Madge.

[18] This is a phrase referring to individuals undergoing a pledge process by a BGLO. The terms “on line” will be explained in greater detail in this section.

[19] In another work, I expand upon a politics of aesthetic that AKA women employed to garner sociopolitical capital. These aesthetic decisions ranged anywhere from their hair to the colors they wore to their speech.

[20] This was excerpted from an oral history with Madge.

[21] In my interview with Lisa, she fondly recalled lining up with the Ivies in the wee hours of the morning to beat the pledges of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated (DST) to breakfast. Since AKA was founded first, Ivies also needed to be first.

[22] In my oral history with Madge, she emphasized the amount of time Ivies spent together studying in the library.

[23] This is the title given to the first person on line. Lines are typically ordered according to height such that the ace is usually the shortest person on the line.

[24] This is a colloquial term to refer to a line of DST pledges. The Greek symbol for Delta is a triangle, very similar to the pyramid.

[25] The skee-wee is the high-pitched, official sound of AKA.

[26] Big Sister is a colloquial term that pledges used to refer to current members of the chapter. A similar term used by members in other chapters during this time was Prophyte.

[27] This was excerpted from an oral history conducted with Madge.

[28] The yard refers to both the literal green space of an HBCU as well as a broader college or community setting where Black Greek-life proliferates.

[29] This was excerpted from an interview with Jada.

[30] In another part of the interview, Jada mentioned being arrested in front of a local grocery store for protesting to urge the company to divest its funds from South Africa.

[31] Stepping (or step dancing) is a “percussive dance in which the participant’s entire body is used as an instrument to produce complex rhythm and sounds through a mixture of footsteps, spoken word, and hand claps” (“Stepping,” 2020). While it is not exclusive to BGLOs, stepping does originate from BGLOs from as early as their inception. African American studies scholar Deborah Whaley gives a nice analysis of stepping in her book chapter, “Stepping into the African Diaspora: Alpha Kappa Alpha and the Production of Sexuality and Femininity in Sorority Step Performance” (2010).

[32] This was excerpted from an interview with Alice.

[33] This refers to the nine junior and senior women who founded AKA in 1908, before they enlisted seven sophomores to the group.

[34] This designation refers to Sorors who have passed away. Ivy Beyond the Wall ceremonies are the sorority’s official rite of mourning a Soror’s death as well as ensuring safe passage of the Soror into the afterlife.

[35] The graduate advisor is a member of the sponsoring graduate chapter whose job is to supervise and advise the undergraduate chapter.

[36] The reveal refers to the part of New Member Presentations when the mask, in this case, comes off and the public learns the identities of the newest members of AKA. Each new member introduces their new AKA self to Greek and non-Greek audiences.

References

“Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated.” 2020. Wikipedia, 31 Jan. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpha_Kappa_Alpha.

Bradley, Barbara. 1990. “A Pledge of Change from Alpha to Omega: Blacks Worry Greek Reforms May Go Too Far.” The Commercial Appeal, 15 Nov.

Buch, Elana D. & Karen M. Staller. 2007. The Feminist Practice of Ethnography. In Feminist Research Practice, ed. Sharlene Nagy, Hesse-Biber, Patricia Lina Leavy. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412984270.n7.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. Taylor & Francis E-Library.

Collison, Michelle. 1990. “8 Fraternities and Sororities Announce an End to Hazing.” The Washington Post, 19 Feb.

Cooper, Brittney. 2017. Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Craig, Maxine Leeds. 2002. Ain’t I a Beauty Queen? Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race. New York: Oxford University Press.

Davis, Dána-Ain and Christa Craven. 2016. Feminist Ethnography: Thinking through Methodologies, Challenges, and Possibilities. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

“Founders.” Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated, aka1908.com/about/founders.

“Gibson Girl.” 2019. Wikipedia, 17 Oct. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gibson_Girl.

Gimlin, Debra. 2002. Body Work: Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Graham, Lawrence Otis. 1999. Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

“Hedera.” 2019. Wikipedia, 23 Dec. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hedera#Cultural_symbolism.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy. 2007. The Practice of Feminist In-Depth Interviewing. In Feminist Research Practice, ed. Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber, Patricia Lina Leavy. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. dx.doi.org/10.4135/978141298270.n7.

“High-Heeled Shoe.”2020. Wikipedia, 4 Feb. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-heeled_shoe.

“Kitten Heel.” 2019. Wikipedia, 18 Aug. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitten_heel.

Leavy, Patricia Lina. 2007. The Practice of Feminist Oral History and Focus Group Interviews. In Feminist Research Practice, ed. Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber, Patricia Lina Leavy. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412984270.n7.

Marriott, Michel. 1990. “Black Fraternities and Sororities End a Tradition.” The New York Times, 3 Oct., B8.

McNealey, Earnestine Green. 2006. Pearls of Service: The Legacy of America’s First Black Sorority. Chicago: Alpha Kappa Alpha.

Mills, David. 1990. “Fraternity Violence: The Pledging Debate: The Greeks: There Is a Move Afoot to Do Away with Hazing and the Traditionalists Are Outraged and Vow to Fight.” Los Angeles Times, 24 Jul.

—.1990. “The Wrongs of the Rites of Brotherhood: Leaders of Black Fraternities Move to End a Cruel Tradition of Violent Hazing.” The Washington Post, 18 Jun., B1 & B6.

Munem, Bahia. 2013. Identifications, Differences and Silences in Fieldwork. In Conference on Religious Alternatives in Latin America, Porto Alegre. ufrgs.br/xviijornadas/cd-virtual-textos-completos/.

“Stepping (African-American).” 2020. Wikipedia, 22 Feb. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stepping_(African-American).

Turner, Victor. 1969. Liminality and Communitas. In The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

Whaley, Deborah. 2010. Disciplining Women: Alpha Kappa Alpha, Black Counterpublics, and the Cultural Politics of Black Sororities. Albany: SUNY Press.