Interview with literature scholar Tabea Linhard

In the spring of 1939 supporters of the defeated Spanish Republic had to flee north across the Pyrenees. Roughly a year later, Jewish and antifascist refugees took the same paths to flee south, on their way to Lisbon, and from there to the Americas. “Yet for both groups these clandestine border crossings hardly were the end of their ordeal,” says Tabea Linhard, a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities and a professor of Romance Languages and Literatures, International and Area Studies, and Comparative Literature.

The exile and transit routes for these refugees intersected in various other locations: in France, where many of the “undesirable” foreigners were taken to prison camps, in North Africa and in Mexico. “Mexico was one of the very few countries that supported the Spanish Republic all along, and 20,000–25,000 exiles settled there,” she says. Mexico City, a center of culturally vibrant antifascist activities, became the adopted home of writers such as Max Aub. Fewer writers exiled during World War II found asylum there, however, with the city receiving a proportionally small number of refugees. Linhard explores their work and their circuitous journeys in her new book project, “Unexpected Routes: Exile, Geography and Memory.”

What is your goal with this book?

My book is about how refugees made it out of Europe and to the Americas, via North Africa, in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and during World War II. Escaping from fascism was tremendously difficult and implied facing cruel bureaucracies, constantly shifting borders, and prejudice in the transit and exile countries. I am interested in the ways in which the refugees experienced and chronicled their journeys from Europe to the Americas. Their voices reveal myriad contradictory emotions and attitudes: fear, nostalgia, hope, optimism, self-righteousness and even chauvinism. I think that if we do not pay attention to these often raw and extremely contradictory documents, we miss part of the story of what (until 2015) had been the most massive forced displacement in history.

How did you select the group of writers you’re looking at?

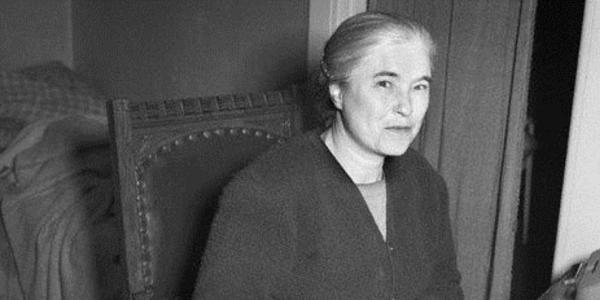

While I was conducting research for my previous book, I came across The Excursion of the Dead Girls, a novella by German writer Anna Seghers (1901–83). The text was first published in Mexico and in Spanish translation in 1944. Seghers wrote it while she was recovering from a severe traffic accident and after finding out that her mother had been put to death in a concentration camp. Seghers’ work led me to other German writers who had settled in Mexico and also made me curious about how this cohort of writers related to another community far more familiar to me: the Spanish Republican exiles in Mexico.

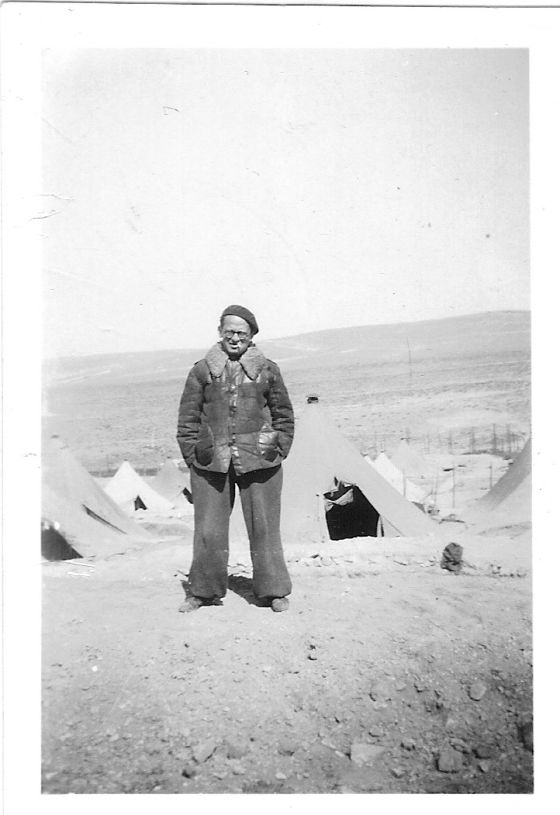

Max Aub (1903–72), for example, belonged to the latter group. He and Seghers coincided in Valencia in 1937, in Paris and eventually in Mexico City. Ruth Rewald also met Seghers in Paris, where Rewald published her Janko. The Boy from Mexico (1934), a book about statelessness written for young audiences. Rewald, however, would never travel to Mexico, as she was killed in Auschwitz in 1942, as was her young daughter Anja two years later. Hans Schaul, Rewald’s husband, was the only member of the family who survived the war. In 1943 he was imprisoned at a camp in Djelfa, Algeria, the same camp where Aub had been incarcerated in 1941.

What common experiences did the exiled writers face? In what ways do you see them writing about their exile?

The writers express different degrees of awe and perplexity about the places they crossed and where they settled. These are places that for the majority of them had only existed on an atlas, on a postcard or in imaginary worlds of exotic adventure. Many of the German writers tended to imagine Mexico (and the Americas) to be similar to the worlds that pulp author Karl May (1842–1912) had created in his novels about the Wild West. May, said to have been Hitler’s favorite author, had actually never left Europe. The writers I study were committed antifascists, they denounced imperialism and racism, and yet their works bubble with exoticizing, Orientalist and even prejudiced tropes and narratives.

Tell us about the approach to maps you take in the book. Why is the combination of geovisual tools and textual analysis important?

Most of the refugees’ itineraries were complex and labyrinthine, and I needed to incorporate maps in order remember who was where, when and why. Yet I wanted maps to do more than serve as an illustration of the texts. I began tinkering with geovisual tools in order to find ways in which maps could help us understand how these refugees experienced specific places. About a year ago I came across a map that for me beautifully illustrated the experience and the memory of displacement. It is the complete opposite of a high-tech map: a hand-drawn map that young Fritz Freudenheim drew of his family’s path from Berlin to Montevideo. The map (archived at the Jewish Museum in Berlin) follows some cartographic conventions and undermines others (scale, legend), which, in my view, is what makes it so effective.

Is there a story that made a particular impact on you during your research?

In 1943 Seghers was run over by a car in a major thoroughfare in Mexico City and left for dead. As she was recovering from her injuries, a friend gave her a wooden figure of Saint Christopher, patron saint of travelers. Seghers was Jewish and a lifelong member of the Communist Party. And yet, for the rest of her life Saint Christopher traveled with her. It is unclear whether Saint Christopher even existed and his name was dropped from the calendar of the Roman Catholic church. But the wooden figure can be found in Seghers’ home, now a memorial, that I visited in Berlin in a few years ago. After some negotiating I was allowed to take a photo of the figure. I promised I would not reproduce the picture, but I like to bring it with me whenever I travel.