Interview with Faculty Fellow Akiko Tsuchiya

By the mid 19th century, most of the world powers had agreed to ban the importation of enslaved people from Africa, the U.S. having outlawed such trade in 1808 and Great Britain, France, Spain and the Netherlands having legally banned the practice by 1820. Yet, in the Spanish colony of Cuba, the transatlantic slave trade remained an illegal but lucrative economic activity well into the 1860s, owing to the labor demand to support the sugar plantations on the Caribbean island, says Faculty Fellow Akiko Tsuchiya, professor of Spanish and affililate faculty member in women, gender and sexuality studies. In the face of such powerful economic interests and despite their own subjugated position in society, Spanish women spoke out against slavery in ways that compelled all members of society to face the horrors of bondage taking place thousands of miles away. Tsuchiya details it all in her book in progress, “Spanish Women of Letters in the 19th-Century Antislavery Movement: Transnational Networks and Exchanges.” Read on for a preview of her project.

What is your book about, briefly?

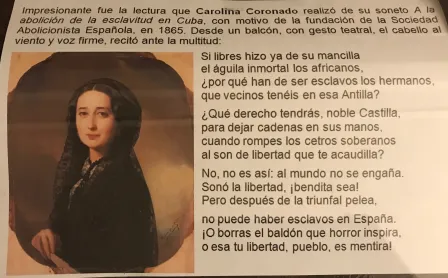

My book investigates the social and cultural role that Spanish women writers and intellectuals (“women of letters”) played in the antislavery movement of the 19th century, both within and beyond Spain’s national borders. Although many women actively championed the antislavery cause through their writings and activism, they were often relegated to the shadows of their male counterparts. Most of these women did not give speeches or write political pamphlets, as the men did, so they did not receive the same public attention. One of my objectives is to recover these women’s voices, but beyond that, there are two major questions that interest me: first, how these women negotiated their place in a male-dominated antislavery movement to achieve their political aims; and, second, how their activism enabled the creation of new arenas of political participation for women in the liberal public sphere. In the second part of the book, I shift my focus to the transnational networks that Spanish women abolitionists formed with those outside of Spain’s national borders, in other parts of Europe, the U.S. and Spanish America.

Was the activism of these women welcome? What effect did their activism have?

Women were assigned separate roles within the antislavery movement, and most of them did not see their antislavery activities as challenging male authority or female domesticity. Hence, on the surface, they were not perceived to be threatening to the masculine status quo, even if some men were made uneasy by women’s presence. We can see women’s impact on two levels. First, some of these women were able to reach a different audience by publishing in magazines edited by women that addressed a mostly female public. For example, the antislavery writer Faustina Sáez de Melgar directed the magazine La Violeta (Madrid, 1862–66), whose function was to “educate” women in accordance with the bourgeois ideals of domesticity. Yet, among the pages of this presumably conservative magazine were articles that publicly denounced slavery. Second, many of the fictional writings — novels, plays and poetry — of these female abolitionists featured representations of enslaved Afro-descendants, which was not common in Spain, as slavery and colonialism usually remained a subtext in the canonical literary works of the period. While these representations of racial otherness were not without problems, they made the oppressive conditions of enslaved persons more present in the minds of Spaniards who were geographically removed from the colonies where slavery was being practiced.

Tell us about the sources you’re using — plays, letters, diaries, travelogues, etc. — what do they add to your research?

When we study women’s cultural history, it is crucial to consider not only their published work but also their experiences of everyday life, which help us to become more aware of the sum of cultural forces that shape their attitudes, values and assumptions. Since historical documents on women are scarce, sources such as private letters, diaries and travelogues are important in shedding light on different facets of the writer, her society and the historical moment in which she was living and writing. For example, perusing the letters of the social reformer and antislavery writer Concepción Arenal (1820–93) allowed me to get a better sense of the social circles in which she traveled and the interactions she maintained with other liberal thinkers of her times.

Why is this the right time to be writing about this history?

The legacies of slavery have become an important subject of public discourse and humanistic inquiry in recent years, both in the U.S. and in Europe. In the specific case of Spain, immigration has become a pressing area of concern, particularly in view of the racist treatment to which immigrants from Africa, and elsewhere, have been subjected by the Spanish government and society. Anti-racist and immigrant-rights groups have gotten mobilized in recent years, drawing connections between colonialism of the past (the enslavement of Africans) and that of the present (racism against African immigrants in Spain).

For example, just this past year in Barcelona there was a public proposal to rename a square that holds the name of a slave trader after a Guinean immigrant who died at a detention center — as an act of reparation. Spain has yet to come to a reckoning with the legacies of its colonial past, but in light of the historical memory movement following the end of the Franco dictatorship, the time is now ripe for the nation to also confront its colonial history and to recognize those who fought to end slavery.

Headline photo: “Trinidad, Cuba” by Flickr user serena_tang CC BY 2.0