John Powers is assistant professor in the Film and Media Studies program.

Film and Media Studies Colloquium Lecture Series

Free and open to the public

Stan Brakhage was cinema’s leading experimental filmmaker and one of the principal architects of cinematic modernism. Between 1952 and 2003, Brakhage completed nearly 400 films and eight books of film criticism and theory. Dozens of his films, including Anticipation of the Night, Mothlight, Dog Star Man and Scenes from Under Childhood, are acknowledged masterworks. For an entire generation of filmmakers and viewers, the phrase “By Brakhage” exemplified the idea that cinema could be a personal expression on par with poetry, music and painting.

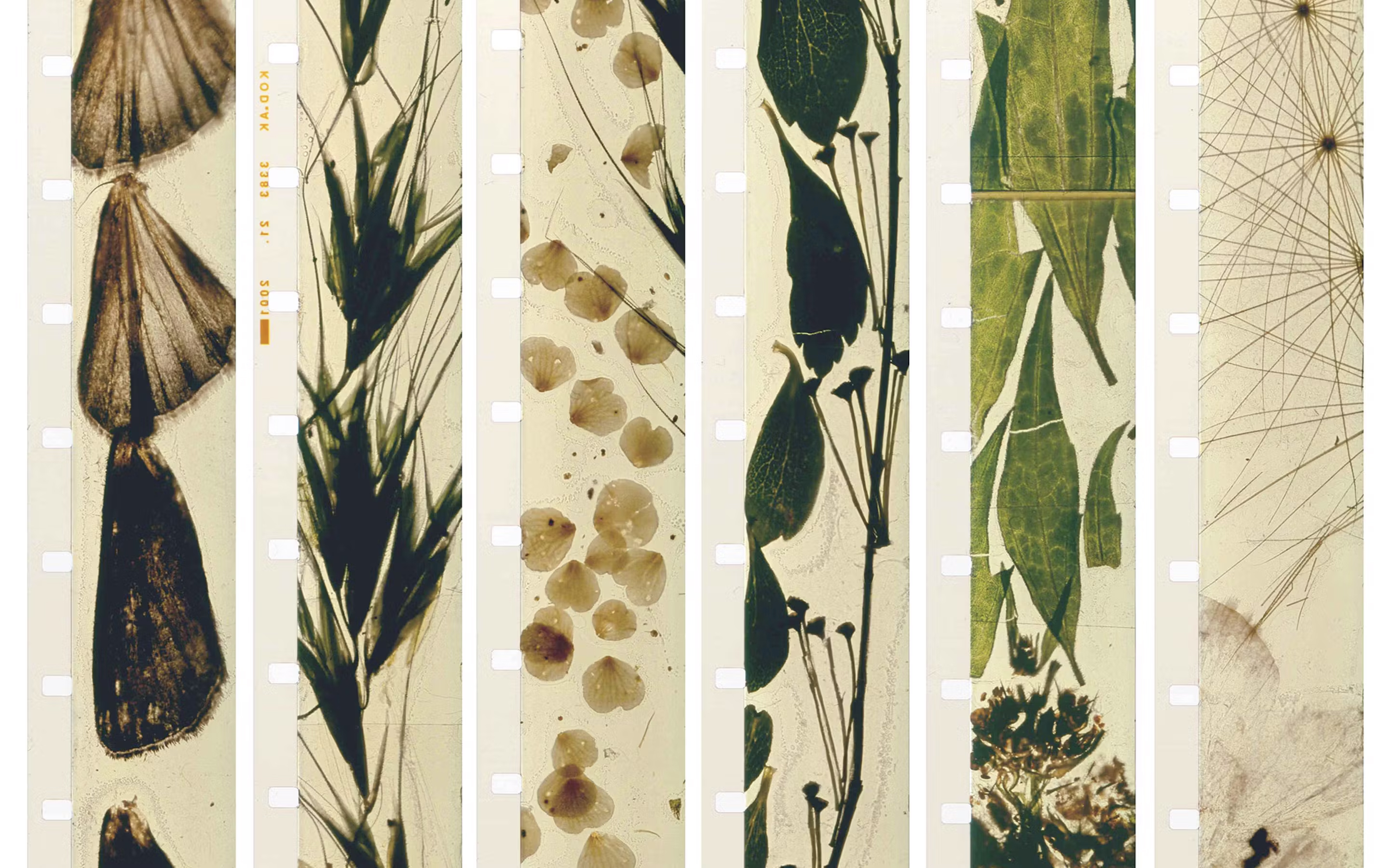

Brakhage’s career was forged in the crucible of the Beatknik 1950s and countercultural 1960s, but his continuous artistic reinvention prompted one of his peers to dub him “America’s Picasso.” The techniques he pioneered, most notably rapid editing, handheld camera, lens flares and physical manipulation of the filmstrip, came to define experimental cinema, but they were also absorbed by advertising, music videos and Hollywood.

His lifelong crusade to transform vision — to “imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective” — aligned cinema with revolutionary developments in cognitive science, psychoanalysis, education and modern art and literature. His refusal of the separation between art and life, most directly evident in the many films that feature his first wife, Jane, and his five children, elevated the home movie to the status of art. More inspired by modernist poetry and music than cinema, Brakhage’s cabin in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains became a site of pilgrimage where John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Bruce Conner and other key figures in 20th-century art would share their work and discuss aesthetics and politics. At the same time, Brakhage’s nonstop lecturing and long teaching career at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Colorado Boulder made him a public figure and ambassador for film art.

Brakhage’s work is cited in nearly every book published on experimental film, but, remarkably, no biography has been written. On September 26, 2024, in conjunction with the newly launched Film and Media Studies colloquium series, I will present a portion of my in-progress biography on Brakhage that attempts to account for the totality of his life and art: his films, writing, teaching, artistic and intellectual influences and the personal relationships that made his achievements possible.

More specifically, the subject of my talk will be a series of lectures on film history that Brakhage presented at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Under the title “A History of Motion Picture Art,” Brakhage profiled legendary directors Georges Méliès, D.W. Griffith, Sergei Eisenstein and Carl Theodor Dreyer in the form of written essays delivered to Chicago’s artgoing public and SAIC students seeking college credit.

It is well known that these lectures launched Brakhage’s teaching career, but I argue that they originated as part of a broader effort for Brakhage to position himself as an intellectual in the mold of Norman Mailer or Leonard Bernstein: as an accomplished and dynamic artist whose opinions on the history of his medium would be valuable to the general public. SAIC provided Brakhage not only a steady paycheck but also a means to introduce himself to the public as an authoritative commentator on film history and art in general.

Although the term “public intellectual” would not be coined until the 1980s, there was no shortage of writers and thinkers who addressed a para-academic public when Brakhage decided to expand his audience beyond experimental film circles. But filmmakers were markedly absent from this intellectual sphere, which was dominated by novelists, literary critics and sociologists. What kinds of issues and what manner of self-presentation could connect Brakhage’s areas of expertise with the interests of this cultural marketplace?

Drawing on archival materials from the Brakhage Collection at the University of Colorado Boulder and the SAIC Library & Special Collections, my talk will place Brakhage’s intellectual activities in a more robust social context. But it will also shed light on a moment before the institutionalization of cinema studies as an academic discipline, revealing an untaken path for film historiography and its role in the public humanities.

Headline image: Still from The Dante Quartet (1987), a handpainted short film by Stan Brakhage.