Interview with medieval French literature scholar Julie Singer

By the 15th century, the admonition that “children should be seen but not heard,” was already circulating in Europe. Their younger peers, of course, were physically and developmentally limited in their ability to talk. So, when the writers of medieval French texts attribute utterances and speech to their youngest characters, what are they telling us?

That question has propelled Faculty Fellow Julie Singer, associate professor of French, in her third book project, “Out of the Mouths of Babes: Children’s Voices in Medieval French Literature.” Singer notes, “Far from being trivial episodes, these often-charming literary portrayals of infant communication are often tied to deeper questions.”

Read on for a peek at her work-in-progress.

Briefly, what is your book about?

The English word infant and the French word enfant both come from the Latin infans, which literally means “unable to speak.” In my new book I’m looking at the places in medieval French literature where toddlers, infants, and even fetuses do talk. I’m finding that the voices of these very minor characters are used as test cases to work through some very important questions about the human condition: personhood, the interplay of nature and nurture, innocence, justice, responsibility.

How are children featured in writings of this period?

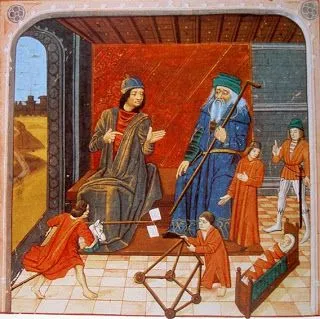

Children appear frequently in medieval literature, especially in epics, which often have a genealogical focus, and in romances, which will typically devote a few lines to the childhood of the future hero in order to show that he’s been exceptional from the start. But the role of these child characters, particularly in the courtly texts that tend to garner the most scholarly attention, is usually quite small. As my project has developed, I’ve found myself working more with literary genres that are less studied today — such as devotional manuals and other religious writings for lay readers — but that were very widely read in the Middle Ages. This is where the really weird stuff starts to happen…

Can you give an example quotation from one of your texts?

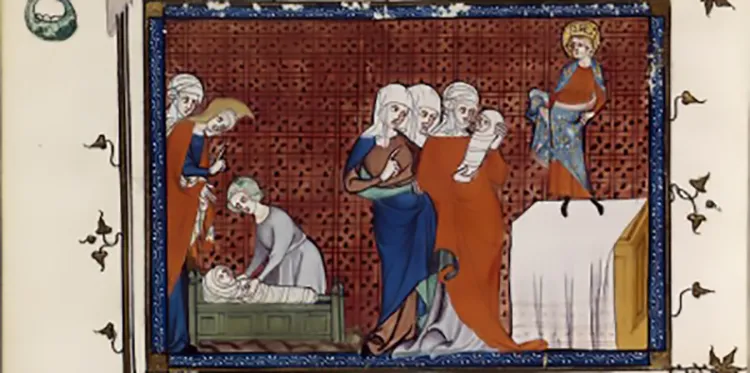

In the medieval West, the conventional wisdom holds that newborn boys cry out “Aahhh” and newborn girls cry out “Ehhhh.” Their cries are interpreted in various ways: as simple interjections expressive of discomfort, as the audible trace of biological sex difference, as the two syllables of the name Eva (Eve), even as abbreviations for long lamentations about the misery of the human condition. The discussions of these interpretations end up shedding light on major medieval debates about speech, reason, and the mechanisms by which language can signify.

Another neat example is a fifteenth-century poem that is the first text in which a number of French baby talk words are written down. Most of these words (like dodo, for “sleepy time”) are still used today! The poem is very cute, but I think it also has a lot to tell us about how some seemingly transparent concepts like “native” and “foreign” language were constructed in the multilingual environments of late medieval courts.

Oh, and did I mention I have talking fetuses?

How does this current project relate to your first two books, Blindness and Therapy in Late Medieval French and Italian Poetry and Representing Mental Illness in Late Medieval France: Machines, Madness, Metaphor?

My first two books are plainly engaged with disability studies and a history of the body, more so than the current project. However, in all three books I am working through the ways in which, for medieval writers and readers, experiential knowledge was mediated by the body but also by language.

In my first book, I was thinking about the ways in which figurative language can serve as a supplement to the body, providing alternate ways of knowing. In the second, I was thinking about how scientific metaphors were used to construct “mental models” that allowed writers to work through politically sensitive questions about reason and governance.

While the new book does still incorporate some of the tools of disability studies — especially in the chapters about feral children and mute children — I am taking a much broader approach to the questions of language and subjectivity. In a way, for medieval writers, children are the ultimate “disabled” subjects: socially marginalized, utterly disenfranchised regardless of social status, physically weak, unable to advocate for themselves. While this sort of disability might be seen as temporary from a modern perspective, medieval people evince quite a different view: this “disability” is a permanent part of the human condition, one that is obscured by the veneer of adult civilization. And so children, especially helpless infants — weaker even than other newborn animals — are the truest representatives of what it means to be human.

“For these writers, there are many truths that only the most marginalized voices can express.”

How are the questions about personhood and subjectivity explored in your work relevant today?

The question of fetal personhood, and when life begins, is obviously still a hot-button issue today. Medieval writers didn’t reach a consensus on this matter either, but they offer a number of fascinating perspectives on the question. More generally, I think my project is relevant because of the ways my medieval authors explore what happens when the “little guy” (literally, in these cases!) speaks truth to power. For these writers, there are many truths that only the most marginalized voices can express, and I think it’s very important for us to attend to that.

Headline photo: “Oli Laughing” by David Long (CC BY 2.0)