Katja Perat is a PhD candidate in the Program in Comparative Literature’s track for international writers and a Graduate Student Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. She is author of The Masochist, a serio-comical fictional romp through the fin de siècle Habsburg Empire.

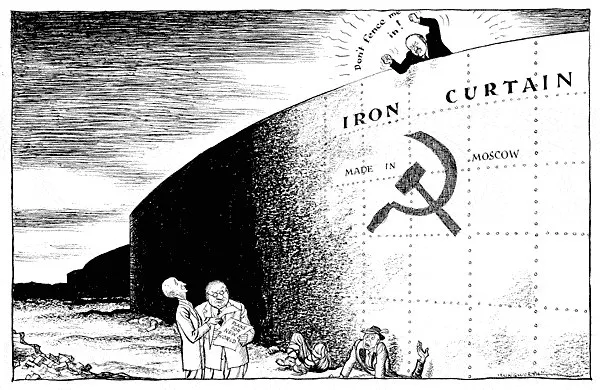

Metaphors shape the way we think. In 1946, Winston Churchill’s “Sinews of Peace” speech united the term “Iron Curtain” with a line on the map, stretching from the Baltic to the Adriatic Sea. In doing so, he crafted one of the most influential metaphors of the 20th century, one that shaped the lives of many living in its shadow.

His vision of a Europe divided into two unequal parts — the West holding political, moral and intellectual superiority over the East — was not new. As Larry Wolff argues in Inventing Eastern Europe, orientalizing approaches to the mapping of Europe have been a part of British and French vocabularies since the Enlightenment. Churchill’s curtain, though, gave this long-standing search for “civilization’s last frontier” within the European continent the desired air of materiality, launching myriads of discursive and political struggles to identify “the last Western state in Europe” that have not been exhausted with the end of the Cold War context that created them.

From the pro-liberal (and largely intellectual) attempts of the mid ’80s to salvage Central Europe as distinct region separate from Eastern Europe and eager to adopt Western-style liberal democracy, to the contemporary anti-liberal politics presumably designed to defend this same Central Europe from Western-style multiculturalism, both cultural and political discourses of the region residing on top of Churchill’s imaginary line on the map have been riddled with the desire to move this line eastward.

In his 1983 Tragedy of Central Europe, Milan Kundera, one of the leading proponents of Central Europe as a cultural unity, argues the region is to be understood as part of the West that was kidnapped by the East, “driven from its own destiny, beyond its own history” to the point where it lost “the essence of its identity.”

In a time when postcolonial theory launched a wave of criticism concerning eurocentrism, cultural elites of Central Europe found themselves longing for a European belonging they felt cast out of, placing the blame for this exclusion on the political machinations of the Soviet Union. As an intellectual trend — and a strategy for many of these authors to secure their place in the field of World literature — the idea of Central Europe as an attempt to articulate the ways of inhabiting the Iron Curtain largely internalized the binary logic of division and difference. This approach often used the same orientalizing strategies in regard to the Soviet Union and even in regard to itself — articulating its position as one of underdevelopment that must aspire to reach the standard of modernity proposed by Western Europe and the U.S. For Central European cultural spaces, Churchill’s divisive ideation, central to the discourse of the Cold War, became a metaphor-turned-flesh. For metaphors, as it turns out, also shape the way we feel, how we understand ourselves and our place in the world.

In my research dealing with how the Cold War shaped Central European fiction, I became particularly interested in why one of the chief analogizing props for modes of Central European cultural experience became female masochism. From Elfriede Jelinek’s infamous The Piano Teacher to Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, representations of female sexuality centered around its presumed “natural” propensity for masochism became the central vehicle for the representation of the internalization of feelings of shame and feelings of inadequacy experienced on a level of cultural belonging.

This gendering of a socially experienced affect allows the reader to capture how the pressures created by the naturalization of simple dichotomies are experienced and how they contribute to the processes of subject-building, in turn giving shape to both intimate and collective sentiments. In Marxism and Literature, Raymond Williams suggests literature has a unique capacity to express how historical conditions are felt and experienced before any other theoretical discourse managed to articulate them. Since the Cold War has ended and transformed itself into historical material available for analysis, little attention has been brought to the affective toll it took on the places it traversed. Looking back to how their literary production handled the questions of intimacy and sexuality might help us discern the insight we lack.

Headline image by Jakob Braun via Unsplash