Lacy Murphy is a graduate student in the Department of Art History and Archaeology, a Mark S. Weil and Joan Hall Weil Professional Development Fellow and a Graduate Student Fellow in the Center for the Humanities.

Could you identify Algeria on a map if asked? If you answered no, there is a plausible explanation. Not only is the Maghreb nation virtually absent from American curricula and news media, but Algeria itself is, at best, ambivalent about its relationship with Western nations and generally maintains a semi-isolationist approach to foreign diplomacy. However, Algeria has played an important role in global politics since the end of World War II, is geographically the largest on the continent and is among the most advanced in counter-terrorism security and global energy in Africa. For these reasons, it would be wise to pay attention to Algeria.

However, Algeria’s government might not share in that sentiment. And who can really blame the country’s officials for their dubious disposition toward their Western counterparts? During Algeria’s eight-year war of independence (1954–62) from France after 132 years of colonization, an estimated 400,000 Muslim lives were indiscriminately extinguished (although the Algerians claim upwards of 1 million). In addition to these staggering numbers, 2 million were displaced and forced to live in internment camps, where disease and malnutrition were rampant.

The traumatic memory of the war is still fresh in Algeria, too, especially this year as the nation celebrates 60 years of independence. The French government has also recently taken the first meaningful steps toward reconciliation with its former colony, in turn dredging up long-suppressed memories in France of the colonial period and subsequent revolution.

A comparison between the historical discourse, past visual representation and recent discussion about Algeria offers much insight as to why the country continues to preserve its relative anonymity. Such a comparison underscores the impact that language and image can have on the world around us.

The French established authority in Algeria in 1830. At the time, the French government touted the colonization of Algeria as a civilizing mission in which their declared goal was to retrieve the formerly prosperous civilization of ancient times from ruin and to introduce modern European technology, education and medicine.

To justify colonial violence, which involved the large-scale expropriation of Algerian tribal lands and the mass repression of indigenous resistance, the French government portrayed Algeria as an archaic, backward and barbarous civilization caught in an endless cycle of war. The French also portrayed colonialism as a collaborative process in which French colonizers and Algerians worked peacefully to rebuild the colony’s prosperity.

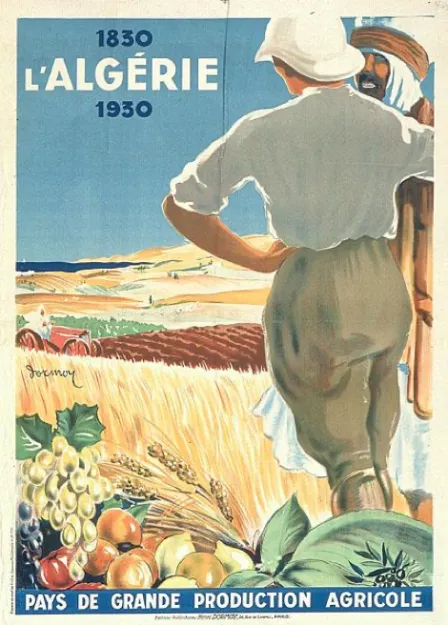

These themes can be observed in French designer Henry Dormoy’s 1930 poster that celebrated the centennial anniversary of the conquest of Algeria and was circulated broadly throughout France (right). In the poster, Dormoy portrays the colonizer as mentor and instructor, tutoring Algerians in the “superior” ways of modern Western agricultural practices. The entire scene is foregrounded by a display of agricultural exports including grapes, lemons, oranges, olives, tomatoes and wheat, symbolizing that the colonial project has come to beautiful fruition.

In stark contrast, Dormoy has characterized the Algerian man seen in the poster as crude and unlearned. In comparison to the sophisticated French colonist, who places a paternalistic arm around the Muslim man, the Algerian appears animalistic. Dormoy has rendered his teeth sharp and menacing.

Western characterizations of Algeria have not changed much since then. A New York Times headline from last month sums it up best: “In Algeria, Veiled from the World, Past and Future Are Shrouded, Too.” The writer goes on to describe Algeria as “a land of absences, of immense potential denied. It is a country hunched in suspicion of the outsider, as if it were still at war.”

Given the West’s long tradition of characterizing Algeria as a war-torn country arrested in development, the language used here should instantly raise an eyebrow. Moreover, the use of terms like “veiled” and “shrouded” to describe the Muslim country can be traced back to a long history of colonialist stereotypes about Muslim nations as hidden, inaccessible or closed off. It also expresses the persisting Western desire to “unveil” or pry open countries like Algeria that resist Western interference.

Without disregarding Algeria’s many troubling human rights violations, the international community is behooved to reconsider the language that is used when describing the people and places of Algeria. Such language openly disregards the legitimate reasons that Algeria has to doubt Western intentions, especially given its current status as a site of geopolitical competition for oil and natural gases. Furthermore, the language and images that the West has used pigeonholes the nation, flattens out the vibrancy and diversity of its culture, and disregards the political agency of its people who have fought continuously to better their lives and redefine their nation.

Headline image by Bilou Bilal on Unsplash