Mary Ann Dzuback is chair of the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; and is associate professor of women, gender and sexuality studies, of education and of history (by courtesy).

For more than 20 years George Sanchez has been exploring the history of multiethnic/racial communities in the United States. His intellectual curiosity arose out of his experience growing up in a multiracial and multiethnic neighborhood in Los Angeles, observing his father and mother navigate the challenges of being immigrants and becoming citizens of their adopted country, as he notes in his groundbreaking study Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (1993). I first read this book when I was teaching History of American Education, a course framed by the question: How do people who have come to the United States “become” Americans — apart from their schooling? What other institutions and experiences are the sources of their education, particularly when they were not born into a white, northern European-American family and community, or were denied full access to equitable schooling in the American colonies or the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries?

Sanchez’s study was a perfect historical text for examining these questions within the singular context of Los Angeles and the Latino/a community. The book is a masterwork for understanding how the migration patterns we take for granted started before there was ever a border between the United States and Mexico, and how those patterns were shaped by changes in work opportunities in southern California, family formation and cultural institutions in Mexico and the United States. Among the most revealing arguments in this book are those articulating the multiple ways immigrants from Mexico influenced American labor union activity, churches, popular culture and the culture of Los Angeles. “Ethnicity,” Sanchez argues, “was not a set of fixed customs surviving from life in Mexico, but ... a collective identity that emerged from daily life in the United States” (11).

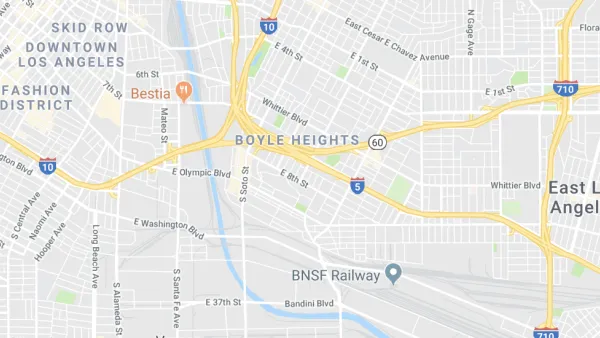

George Sanchez has continued exploring these questions, as a historian and in his capacity as an interdisciplinary scholar and citizen of a number of top universities in the United States. The project he started working on after moving from UCLA, to the University of Michigan, to the University of Southern California (USC) and that he is now completing (“Bridging Borders, Remaking Community: Racial Interaction in Boyle Heights, California”), is a reflection of that commitment.

This current book project also well captures Sanchez’s efforts to link his scholarship to his university administrative responsibilities and his community engagement activities. He has dedicated his professional life to increasing ethnic, racial, and social class diversity in multiple ways. Some examples include his work as director of the Center for American Studies and Ethnicity; director and then vice-dean for college diversity, during which he began USC’s initiatives for first-generation college students and started the Student Food Pantry and Trojan Guardian Scholars for Foster Care Youth; and then director of the Center for Diversity and Democracy at USC. For the past 15 years or more, he has shared the knowledge his institutional activism and scholarship have yielded to make a case for increasing ethnic and racial diversity in the historical profession, student enrollments and faculty appointments in higher education institutions, and university institutional cultures to welcome underrepresented minority students and faculty.

His scholarship has been animated by questions such as: How do immigrants adapt to and change the larger culture they inhabit here in the U.S.? How is their “new” ethnic identity formed? What can the history of Los Angeles tell us about how different ethnic groups have interacted with one another to shape their city in the 20th century? How does power operate in this context, and how does power shift across groups around particular historical moments, political, economic and cultural issues, and what roles do institutions play in these processes?

In his most recent articles and talks, Sanchez has continued to examine democratic activism and political power in urban communities shaped by multiracial coalitions. Further, he suggests how those coalitions can be perceived as dangerous for their ability to foster more liberal and left political activism in the face of exploitative white majority policies. He has explored how power elites reduced that power by, for example, routing highways through urban neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s; deporting undocumented immigrants from the 1930s on; and interning Japanese Americans in the 1940s. Sanchez’s work offers us historically informed means of considering how to create more representative politics, workplaces and educational institutions as we try to bridge geographic, ethnic, racial, social class and cultural divides in the 21st century.

EVENT DETAILS

James E. McLeod Memorial Lecture on Higher Education

Bridging the Divided City: Preparing Students for a New Los Angeles

George J. Sanchez, Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity and History, and Director of the Center for Democracy and Diversity, University of Southern California

Friday, September 27, 2019

3:00 PM

HILLMAN HALL, CLARK-FOX FORUM

Free and all are welcome

RSVPs appreciated; follow link above to respond