Michael R. Allen, a lecturer in the American Culture Studies program and senior lecturer in architecture, landscape architecture and urban design at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, is also an academic researcher, historian, design critic, public artist, critical spatial tour guide and heritage conservationist in private practice. He reviews the latest book by Jenny Price, a public writer, artist and environmental historian and current research fellow at the Sam Fox School.

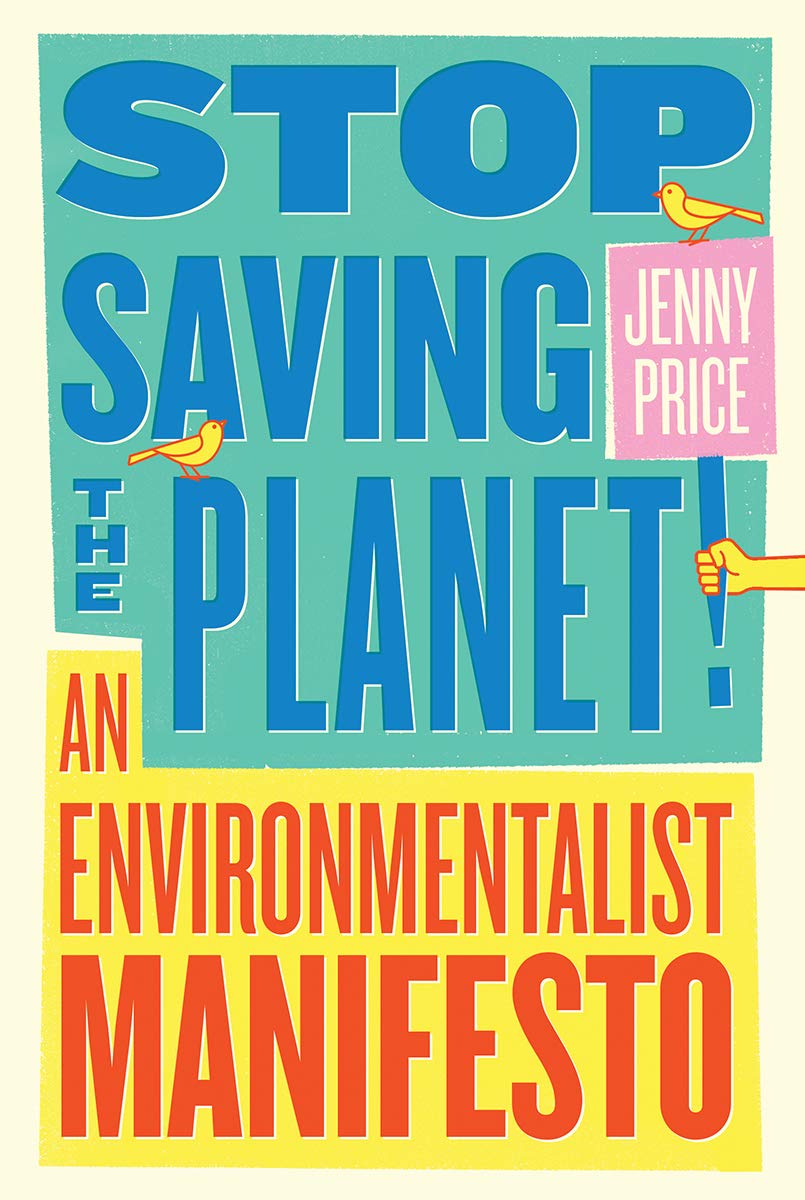

After finishing Jenny Price’s Stop Saving the Planet: An Environmentalist Manifesto, I felt the urge to look up the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website. I wanted to see how much of the official discourse related to Price’s thesis that we need to replace the “out there” environmentalism — which dichotomizes the human and natural realms — with an “in here” theory posing environment, society and economy as connected parts of the world in which we live, 24/7.

Book launch for Stop Saving the Planet: An Environmentalist Manifesto

Jenny Price in conversation with Nathanael Johnson, journalist and senior writer for Grist

Left Bank Books

7 pm | Wednesday, April 21

The EPA has a quotations page, and strangely this is the first one: “But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself,” from Rachel Carson. Perhaps somewhere in the hearts and minds of the government regulators, corporate sustainability stewards and LEED certifiers to whom Price’s book is directed, the truth is already embedded.

In fact, the book — which can be read in a little over an hour, so no excuses for any of the aforementioned — walks a reader through the realms of ra-ra environmentalism that seem hard to believe anyone believes. Exxon’s commitment to alternative energy. Ecologically sustainable seven-bedroom mansions. Cap and trade credits that create a new financialization around finance. Odes to the “planet” as if it is an abstract piece of art needing a conservator’s care.

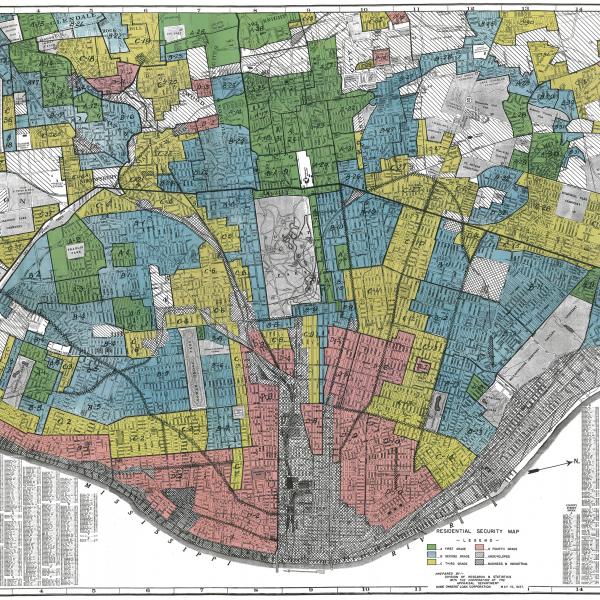

Price locates within the “out there” environmentalism the escape hatch that actually allows for extraction, pollution, consumerism, racism, classism and financialization to mask themselves behind the shields of phony solutions. There is “Green Virtue,” which allows people to moralize their choices without locating them within any social or economic context. There is the insidious “Whole Planetude,” the backbone of corporate campaigns to use environmentalism to sustain their rapacious hold on the planet. Whole Planetude is a doctrine that promotes the idea that any action, anywhere, by anybody will help dig us out of the ecological crises of our time. It’s the planet, not specific locations like Southeast Los Angeles or the West Lake Landfill in St. Louis, that’s at stake. And all actions are somehow equal, so if Union Carbide eliminated bottled water in the workplace, it has done something good for the planet.

As the book unwinds its critique of environmentalism, it begins revealing its real aim: to join struggles for climate, racial and economic justice by demonstrating that our climate crisis is not one of “environment” but one of economy. Capitalism’s promotion of growth through profit drives ecological devastation, and to find out how that has happened, there are specific people who have done specific things to specific places. To liberate the earth, the specific victims of this economy must be set free, not just “the planet.” The specific perpetrators must be brought to justice, not just “people” (or “humans,” as the faddish Anthropocene theory poses in a theory oblivious to race, gender and class).

Price’s steadfast commitment to the joining of struggles overturns what political theorist Ernesto Laclau termed “the denigration of the masses.” In the face of unruly, contradictory popular opposition to power, from the French gilles jauntes to the disaffected coal miners of West Virginia, political figures right and left attempt to reassert the supremacy of state and capitalist institutions. After the January 6 siege of the U.S. Capitol, there is especially a left tendency to double down on rejecting any “populist” outrage expressed in jarring forms.

This zinger of a riddle captures the spirit of the arguments here well: “Can you save more energy by buying 1 Prius and driving it 15 miles or by buying 3 Priuses and driving them 5 miles each?”

Price dares readers to recognize their own elitist bearings in making such a denunciation — an unwillingness to accept that environmentalists (in this case) have crafted a discourse far more palatable to Exxon executives than workers on offshore oil rigs. The core of that discourse is that too much environmentalist rhetoric relies on a false equivalence between the oil rigger’s pursuit of a living wage and the Prius-driving, LEED-certified-office-occupying CEO whose pursuit of profit over all other values is the fundamental problem. In the wake of the litany of corporations and universities hawking diversity, equity and inclusion policies and offices without actually addressing the systemic ways in which white supremacy and male power permeate these institutions, Price’s arguments might inspire critique in other areas.

However, Price does not critique this equivalence to score a simple political point, but instead to draw it across several concrete, real-life examples of ways in which similar judgments mislead. There are some edgy observations, such as that only 3% of plastic is recycled and that municipal waste is only about 3% of the planet’s waste stream. The point is not to discourage recycling — the sort of false populism of ecological denialism in vogue on the right today — but to make it clear that the neighbor who tosses yogurt containers in the garbage is a minor pest compared to Apple, whose products generate so much plastic waste but whose greenwashing schemes inure the corporation to the same kind of scorn.

Conversational in tone, Price’s book comes across like a lively lecture or speech — the kind that elected officials should be making about these issues. Humor speeds along the narrative, also proposing a new form of ecological persuasion that jettisons dour, data-heavy language. This zinger of a riddle captures the spirit of the arguments here well: “Can you save more energy by buying 1 Prius and driving it 15 miles or by buying 3 Priuses and driving them 5 miles each?”

The answer has nothing to do with the Prius. It has a lot to do with the 39 actions that form the ending of the book, in homage to the popular environmentalist “50 Things” style self-help books. There, Price draws the big arguments down to steps (not always small) such as paying one’s full share of taxes, promoting public space, learning about the needs of neighborhood birds to become a better advocate, learning where your money comes from (as important as knowing where it goes) and so forth. All of these planks develop a revolutionary and refreshing platform that takes the environmentalist emphasis on individual actions — the kinds of things we will be bombarded with at Earth Day this month — and raises them to individual actions that have collective benefit.

Price returns to the dream of a “Government Is Us Economy,” where we are not timid to actually ask our government to set human and ecological health as a higher aim than monetary wealth, and she means it. Her compact binds us all together by binding our spheres of living together into “the environment,” where we can see that not all inputs are created equal, and not all actions really cause that much change. We need to replace popular environmentalism, in which we follow ineffective fads that allow certain powers to recuperate our power, with populist environmentalism, in which when we think of the planet, we also think of its people. All of them.

Headline image by Hello I’m Nik via Unsplash