Paige McGinley is associate professor in the Performing Arts Department and director of the Program in American Culture Studies.

Infrastructure doesn’t seem to be the most likely backbone for a feature film. How thrilling, in the end, can it be to watch a bunch of people raising money, arguing about logistics and securing sound systems?

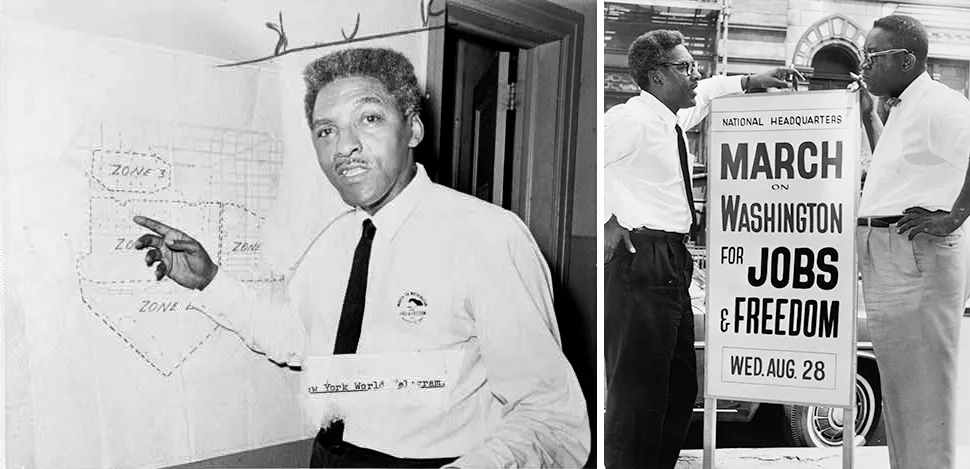

And yet the 2023 film Rustin is just that: a drama about the preparations for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March is, of course, well-remembered for the 250,000 people who filled the National Mall demanding an end to racial discrimination in public accommodations and employment. It is well-remembered for Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, and for Mahalia Jackson’s stirring performance of “How I Got Over.” But the driving force behind the March — the person responsible for its vision, its organization and its planning — was less well known in his own time and remains so in ours. Directed by George C. Wolfe, Rustin seeks to remedy that omission with its rich and compassionate exploration of Bayard Rustin’s leadership — and the way he was sidelined from the movement by those who considered his sexuality a liability.

While the film largely focuses on the months leading up to the March, Rustin’s contributions to the movement extended far beyond this signal event. Raised in a Quaker family in Pennsylvania, Bayard Rustin (1912–87) held a lifelong philosophical commitment to nonviolence. A conscientious objector who spent 28 months in federal prison for refusing military service, he was a student of Gandhi’s Free India Movement and began to experiment with nonviolent direct action in the 1940s. In 1943, he began to lead interracial institutes organized around the study and practice of what he called “creative nonviolence.” These institutes culminated in real-world experiments that tested the compliance of restaurants, movie theaters and swimming pools bound by nondiscrimination ordinances and were important forerunners to the sit-ins, kneel-ins and wade-ins of the 1960s.

In order to prepare participants for direct action, Rustin innovated the use of sociodramas — role-playing rehearsals that allowed participants to explore creative responses to segregation. The sociodrama was a core preparation technique that was used widely throughout the movement over decades, and it’s one we see at work in a pivotal scene in Rustin. Here, Rustin trains the Black New York City police officers who will serve at the March on Washington. Having surrendered their service weapons, they need to practice regulating their own embodied responses to racial hatred and abuse.

The sociodramas were a critical part of the civil rights infrastructure this film represents. We see throughout that Rustin knew the value not only of logistical preparation, but the importance of preparing bodies and spirits for a new world. We see how embodied, how interpersonal, how co-present organizing was for Rustin and his colleagues in this pre-digital world. Yes, there were mimeograph machines and WATS telephone lines, but without Slack, What’sApp and Google Docs, organizers had no choice but to gather together in a dirty room, sweep out the cobwebs, confront their differences and get the job done.

Rustin’s huge laugh, resonant singing voice, tender vulnerability and his commitment to living as an out gay man in a world dominated by the closet all bundled together to make a larger-than-life figure. Colman Domingo’s Oscar nomination as the film’s lead is profoundly deserved; his performance captures Rustin’s charismatic abundance without turning him into a caricature. We are left with a sense of what drew so many to his leadership as well as the humility and selflessness with which he led, in a world so often bent on denying the fullness of his humanity.

Read more about Paige McGinley’s work on the practice of rehearsal in the civil rights movement: People get ready.

Headline image: Rustin promotional image courtesy Netflix.