Rebecca Dudley is a PhD candidate in sociocultural anthropology in the Department of Anthropology and a Harvey Graduate Fellow with the American Culture Studies program. Her historical anthropological research focuses on legacies of the plantation in contemporary industrial agriculture in the Deep South, including the racialization of labor, technology, financing, commodity flows and knowledge on industrial farms. Before beginning her dissertation research, Dudley worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency.

Plantation violence seeps up through the Louisiana silty loam. The ice-cream soil, as the farmers call it throughout the south-central parishes, has been worked and reworked since the 18th century into what is now a post-plantation farmscape. Material remnants of the plantation linger in daily life; hauntings of plantation violence remain spoken and unspoken in memory. This is the site of my inquiry, and Pointe Coupée is my point of entry.

Just after Easter Sunday in 1795, Jean Baptiste Forgeron testified in what became known as the 1795 Pointe Coupée Slave Conspiracy trial. His words, recorded by a French scribe, were crucial for the French and Spanish authorities in this colonial military outpost and emerging sugar plantation economy to get the story on what the enslaved were planning to do, and who should be punished for (not yet) committing a revolt. Forgeron’s testimony was the longest recorded document from the trial, the most detailed and the most exhaustive in describing what precisely had happened, who the leaders and players were and what they had hoped to do.

Forgeron was not, however, a colonial authority. He was an enslaved skilled laborer, working on the LaCour Estate as a blacksmith, evidenced by his name, forgeron — French for blacksmith. On the surface of the evidence at hand, he was the deepest betrayer. How should we read his words? What might we speculate of his motivation, of his inner life? Does that speculation bring clarity to the violence continually unfolding in this peripheral agrarian outpost? These are some of the questions I ask as I comb and recomb through the archives of Pointe Coupée in 1795 — and how this history refracts in today’s social and agricultural landscape.

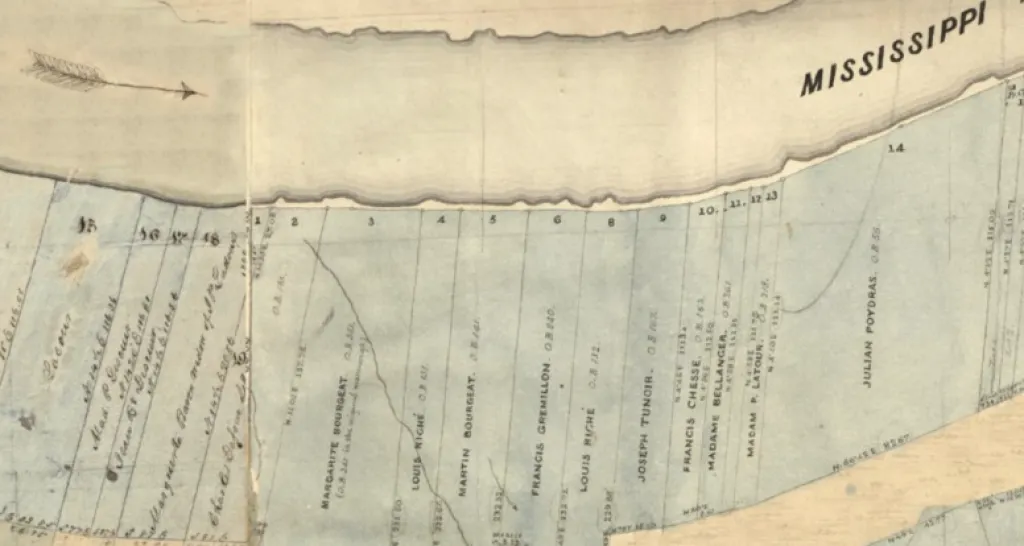

Forgeron was approximately in his late 40s when the trial occurred. He was born in Louisiana (rather than forcibly trafficked from West Africa or the Caribbean, as many others in the enslaved community in Pointe Coupée had been), and he was reportedly unmarried (though this is somewhat dubious, since the marital status of enslaved persons was not respected by those who held the pen). Forgeron worked on one of the two major plantations where the conspiracy (ostensibly) unfolded, the plantation of the Widow LaCour (numbers 14 and 15 in the left corner of the map below). The other key site was the Poydras plantation (number 14, right corner), one of the sugar plantations established by Julian Poydras, considered a founding father of Louisiana. Public memory venerates Poydras as a leader during the transition from French territory to American state, a founder of the state’s public education system and, toxically, as a “gentle” slaveowner. Were this conspiracy trial at the center of his plantation’s history, the viciousness that he exhibited toward enslaved people would have to be attended to.

But the focus right now isn’t on Poydras, the Louisiana hero. It’s Forgeron, the anti-hero of the 1795 Pointe Coupée Conspiracy trial. In the testimony attributed to Forgeron, he points to dozens of conspirators, including men and women with whom he labored on the LaCour Plantation, as involved in the plot. He explains what they were planning to do, what weapons they had amassed, how they coordinated across plantations and swampland and between work and worship and leisure time, and how he had refused to participate. Forgeron’s words betrayed dozens of people with whom he labored both in close proximity on the LaCour Plantation and in the surrounding plantation community, leading to 60 convictions. The 23 most important members of the conspiracy were hung and decapitated, like the leaders of the 1811 slave revolt that would unfold just a few sugarcane parishes downriver, just a few years later. It seems that French colonial leadership was in the habit of using these leaders’ body parts in a form of visual terrorism, in the hopes of deterring other future uprisings, by displaying them on the ends of spikes along the banks of the Mississippi River. Forgeron’s testimony played a vital role giving the state its authority to exercise this violence.

If we read the scribed testimony as a valid reflection of his words, then it follows Forgeron said them, or something close to them. Sophie White’s Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana also attends to trial documents from this era and place. White explains that while the recording practices of the era were careful — with multiple steps followed in a strict process to ensure the transcription was taken accurately — the process of the trial often included torture, particularly if individuals were already perceived as guilty (White 2019). It’s conceivable that Jean Baptiste Forgeron may have been subjected to this kind of routine torture. That his testimony was so helpful to telling the story of this conspiracy prompts me to wonder about the circumstances of its production.

Forgeron worked as a blacksmith, a skilled craftsperson producing the implements of labor — including hoe collars. Hoe collars are, at bottom, objects of labor. Produced by labor for uses of labor. These iron objects emerge in the farm landscape as junk, as rubble, as inconveniences that interrupt present-day industrial farming and other industrial land uses, like petrochemical and plastics production sites. One such piece of iron crossed my path during dissertation fieldwork — a hoe collar, pictured below.

An 18th-century hoe collar gets caught in the gears of industrial agriculture today. In its interruption of the industrial farm operations today, it causes work to momentarily stop. Even though contemporary combines, tractors and rigs are robust, these relatively small bits of iron farm implements can be devastating for them, causing bends and warps that lead to days of stopped work and thousands of dollars in repair. It’s a hassle, one farmer explains to me.

These small bits of iron also present a serious danger to farm workers, if and as they ricochet off fast-moving and powerful farm equipment, flying into the air or skidding across the ground. Inert, it’s junk; in motion, it’s lethal. As a fragment of what could have been used as a lethal weapon, as hoe collars and other farm implements were used in slave uprisings, it poses, like almost all technologies on the farm, a potentially deadly risk to farm workers today.

The hoe, originating time immemorial in West African agriculture, was an essential technology of early plantation production. It is the strength to complement the intellectual techniques of plantation production, a confluence of West African, European and Native ways of knowing and working farmland. This particular artifact, furthermore, emerged close to the historic LaCour plantation site. It could have been a work of Jean Baptiste Forgeron, and it likely was the product of an enslaved skilled laborer, a forgeron. Industrial farms are generally thought of as a modern invention, something that occurred as a dramatic break from agrarian society, sometime after the turn of the 20th century. But this misunderstands and misses how farming today is entwined in these histories of plantation violence, the materials they produce, the racialization of labor and land, the interpersonal betrayals, and liberatory resistance to plantation agriculture.

Headline image by Julian Hochgesang via Unsplash