Salvador Lopez Rivera is PhD candidate in French language and literature and earned a graduate certificate in women’s, gender and sexuality studies.

When most people hear the word “France,” they will immediately picture Paris, with its iconic monuments, world-class museums and charming cafés. They will think of its residents’ glamorous lives, depicted by popular screen and TV characters such as Amélie (in the iconic 1990s movie of the same title) and Emily (from the hit Netflix series Emily in Paris). Few will think of the high-rise buildings outside of city limits where many working-class and Parisians of color live. Even fewer will picture the quiet single-family-home suburbs of Aulnay-sous-Bois, a town that you may glimpse as you ride the train to downtown Paris from Charles de Gaulle International Airport, but that you are unlikely ever to visit unless you know somebody who lives there. Fewer still will visualize any of the thousands of quiet mid-sized towns and rural villages scattered throughout the country that lack tourist attractions.

These communities, nonetheless, are just as much a part of France as Paris. Despite their essential contribution to France’s full story, their residents are increasingly concerned that their lives are not of interest to the world. A new generation of writers is ensuring their stories don’t get left out. Using literature as a tool to give voice to these compatriots, they show that seemingly unremarkable places are fertile ground for conversations about life, class, disability, gender, race and sexuality.

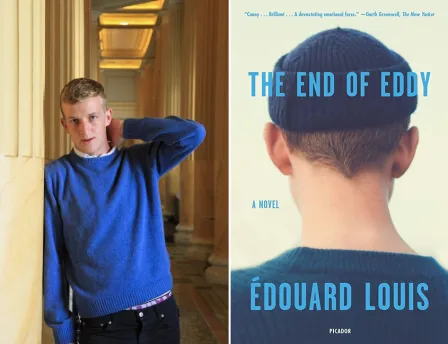

In 2014, a young unknown writer named Édouard Louis released his autobiographical novel, The End of Eddy. It became an instant bestseller in France for two reasons. First, it exposed many middle-class readers to the acute poverty of an industrial village in northern France, a region evocative of the United States’ Rust Belt. Middle-class readers were shocked that a wealthy country like France, known for its welfare state, had failed to alleviate poverty. Second, it confirmed the widespread belief that the predominantly white residents of these small villages held racist and homophobic beliefs. Throughout his childhood, Louis was bullied for being gay, even by some of his relatives. In this “other” France — the one symbolically and geographically far from the Eiffel Tower and the skyscrapers of La Défense business district in Paris — people struggle to pay for food and bills, drop out of high school and vote for right-wing populists like Marine Le Pen. The End of Eddy’s success can be attributed to its ability to expose the struggle of living in the declining French countryside — a story that read like a novelty for those living in the prosperous neighborhoods of large cities like Paris and Lyon.

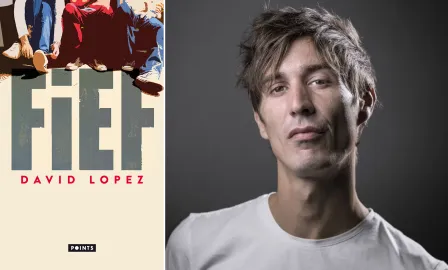

Despite the hardships endured by many residents of small-town France, it would be unfair to think of these communities exclusively in terms of their socioeconomic woes. At the other end of the spectrum, David Lopez’s bestselling novel Fief (2017) shows that while life is difficult in small towns, it can also be joyful. Through the first-person narration of a teen named Jonas, Lopez transforms the commonplace — hanging out with friends, playing video games, practicing for a boxing match at the local gym, taking care of a garden — into something wonderful. Lopez’s novel shows that literature can venture outside the grandiose and find meaning in the ordinary. The post-industrial countryside is gloomy sometimes, but it remains a place where many find love and build meaningful lives. By emphasizing this point, Lopez helps undermine the pervasive ruralism — the discrimination against rural residents — in France today.

Joining Louis and Lopez, others in this cohort of young writers — including Nicolas Mathieu, Simon Johannin and Joffrine Donnadieu — position their narratives somewhere between the tragic autobiographical The End of Eddy and the pastoral coming-of-age Fief. All, however, would agree that the ordinary rural villages, towns and suburbs of France contain stories worth telling. Omitting these stories amounts to providing an incomplete vision of 21st-century France. Thanks to these writers, as well as those belonging to other minority groups like people of color, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ people, French-language literature is filling in the gaps left by previous generations, whose idea of culture privileged the perspectives of wealthy, white urban metropolitan French over everyone else. By portraying ordinary places with nuance, these writers help show how the stock images associated with France do not capture its diversity.

Headline image: Aulnay-sous-Bois, Île-de-France, France by Petit_louis via Flickr