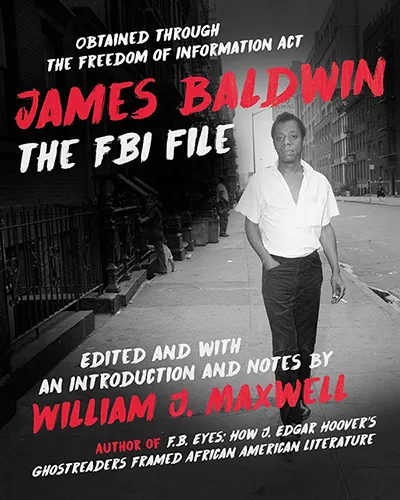

William J. Maxwell is a professor of English and African and African-American Studies.

At least since Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave won the Oscar for Best Picture seven years ago, we’ve enjoyed a genuine as well as official Black cinematic renaissance. Ava duVernay’s Selma (2014), Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight (2016), Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017), McQueen’s own Small Axe anthology (2020), etc.: the list is long and varied, unified only by its assurance that this latest Black film boom is too diverse in focus and style to go the way of the last, exhausted by studio-enforced remakes of New Jacks ’n the Hood. Yet over the past few months, a fresh wave of Black-themed, Black-directed historical dramas — MLK/FBI (2020), Judas and the Black Messiah (2021), and The United States Versus Billie Holiday (2021) — has shown signs of cohering into a relatively consistent genre, one we can call the FOIA film.

Darnell Martin, the director of I Like It Like That (1994), the first Hollywood studio vehicle piloted by a Black woman, recently said this of the withering of the previous Black film heyday of Do the Right Thing (1989) and Daughters of the Dust (1991): “It’s like they set us up to fail.” If the 21st-century FOIA film has its way, being set up to fail by shadowy forces will become a productive artistic subject — perhaps the primary inspiration, in fact, for backward-glancing Black cinema as our post-civil rights era topples and rebuilds the monuments of 20th-century Black culture.

What is a FOIA film, anyway? It’s a film that could only be made after (1) the liberating provisions of the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) were extended to once-secret FBI documents; and after (2) those documents, exposed to public view, have been redefined as master keys to the interaction of modern Black life and the American racial state. It’s a film, then, like Sam Pollard’s documentary MLK/FBI, which reconsiders heroic civil rights history through the grimy lens of FBI repression, the better to preach that the arc of the American moral universe is overlong and not necessarily bent toward justice. It’s a film like Shaka King’s Black Panther drama Judas and the Black Messiah, which deploys the figure of the Black FBI informer as a measure of ambivalent patriotic desire in addition to self-hating racial suicide. In a less abstract nutshell, a FOIA film is The United States Versus Billie Holiday, a lush revisionist biopic, currently streaming on Hulu, which might as well be titled The FBI Versus “Strange Fruit.”

Director Lee Daniels opens not with a close-up of Holiday’s iconic white gardenia, but on an aggressively ugly black-and-white historical photo. As his camera slowly descends over the still image, a thin line of white men, grinning in Depression-era caps and sweaters, reveal themselves as contented lynchers celebrating the burning of a Black man on an open fire. An intertitle follows, superimposed over the standing, anything-but-damaged form of R&B vocalist Andra Day, whose angular variation on Holiday’s plaintive voice becomes the true star of the show. The text explains that the first Lady Day “rose to fame” by performing the greatest anti-lynching artwork of all, “Strange Fruit.” Permanently autographed by Holiday’s haunting contralto, this 1939 protest ballad was originally composed by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish Communist poet and, not purely coincidentally, James Baldwin’s least unhelpful high school English teacher.

In the whole of the film that follows, Holiday is “Strange Fruit,” and vice versa, and the FBI is more effective than any unembarrassed lyncher in thwarting her campaign to wield the tune against the worst of racist violence. “She keeps singing this ‘Strange Fruit’ song and it’s causing a lot of people to think the wrong things,” frankly reports the movie’s specimen G-Man. A young, equally candid Roy Cohn, on loan from Angels in America and various intellectual histories of Trumpism, adds that “People are calling the song a musical starting gun for the so-called civil rights movement.” For Daniels and his screenwriter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, the errand of modern Black art is to release, then flow with the current of progressive Black politics. And the price inevitably paid by the Black artist-as-Black politico is relentless harassment from J. Edgar Hoover’s vindictive intelligence bureaucracy, its agents armed with inside knowledge of the social sway of Black culture. In The United States Versus Billie Holiday, as in the other FOIA movies, to be a great Black leader or great Black artist — the two callings are indistinguishable — is to be visited, backstage and on one’s deathbed, by clued-in critics from the U.S. security state. On the lowest frequencies, the still-focusing genre of the FOIA film pictures a creative Black will-to-resistance inescapably chained to canny, often deadly federal enemies — a pairing of Afro-optimistic impulses and Afro-pessimistic assumptions which finally tells too much of our time, and promises an explosive synthesis to come.

Headline image by Wesley Tingey via Unsplash