Erin McGlothlin is an associate professor of German and Jewish studies.

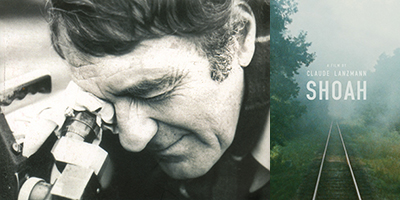

On July 5, 2018, Claude Lanzmann, the renowned French documentary filmmaker, died at the age of 92. He left behind an unparalleled oeuvre of films, the most celebrated of which is his mammoth masterwork Shoah (1985), which painstakingly reconstructs the immense and complex history of the Holocaust — particularly the experience of people who were murdered in the National Socialist genocidal killing centers in occupied Poland — through the contemporary testimony of eyewitnesses. With a running time of nine-and-a-half-hours in its theatrical release, Shoah juxtaposes Lanzmann’s own filmed interviews with dozens of Holocaust survivors, bystanders and perpetrators (some of the latter of whom Lanzmann filmed clandestinely) alongside long sequences of footage of present-day locations in which the genocide took place.

As Holocaust literature and film scholar Sue Vice, in her 2011 book on Lanzmann’s film, writes about the aesthetic and narrative composition of the film, “This is a deceptively simple format, yet Shoah’s standing is unrivalled in both film history and Holocaust representation.” While Lanzmann is best known for the singular achievement that constitutes Shoah, his opus also contains a number of other documentaries about the Holocaust, including A Visitor from the Living (1999), Sobibór, October 14, 1943, 4 p.m. (2001), The Karski Report (2010) and The Last of the Unjust (2013). Lanzmann’s last film, The Four Sisters, which features his interviews with four women who had survived the Holocaust, premiered the day before his death.

All of Lanzmann’s documentary films about the Holocaust, which collectively constitute what Vice terms his “life’s work,” are based on a massive, historically singular archive of film footage that Lanzmann began creating in the early 1970s for Shoah. Far and away the largest part of the archive comprises footage of the astonishing and often historically anomalous interviews Lanzmann conducted in more than half a dozen languages in over ten countries with many dozens of people, including Jewish survivors, German perpetrators, Polish eyewitnesses and Holocaust historians, while a smaller but substantial portion of the collection contains location footage of the present-day sites of mass murder during the Holocaust, especially those of the former killing centers at Auschwitz, Maidanek, Treblinka, Bełżec, Sobibór and Chełmno, the latter four of which contain few physical indications of the genocide that happened on their soil. (In all his films Lanzmann deliberately refrained from including Holocaust-era footage, preferring instead to focus on the traces of the genocide in the contemporary landscape.). Filmed over the course of over 10 years, this extensive collection contains over 230 hours of footage, yet only around 21 total hours of this footage appears in Lanzmann’s films, meaning that over 200 hours of what film scholars refer to as “outtakes” were not released theatrically.

In 1996, Lanzmann ceded control of these materials — which collectively weighed over two tons — to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), which owns the Shoah archive jointly with Yad Vashem (the Israeli national Holocaust museum and research institute). Since that time, the USHMM’s Spielberg Film and Video Archive has worked tenaciously to preserve and restore the thousands of film and audio reels (some of which had significantly degraded while in storage), to convert them to a digital format and to make them accessible online not only to researchers and filmmakers (including Lanzmann himself, who utilized the USHMM’s collection to make his post-Shoah Holocaust documentaries), but also to general members of the public. At this time, around 85 percent of this extensive archive is available for instant viewing on the USHMM’s website. (Thanks to Lindsay Zarwell and Leslie Swift of the USHMM’s Spielberg Film and Video Archive for the technical information on the Shoah archive. Their chapter, “Inside the Outtakes: A History of the Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,” is included in a forthcoming book on the outtakes edited by Brad Prager and me, titled “Inventing According to the Truth: Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah and its Outtakes.”)

The Shoah collection of outtakes is a valuable resource for historians, since it is one of the earliest archives of Holocaust testimonies and moreover is of very high quality, as Lanzmann was a skillful and knowledgeable — if idiosyncratic and demanding — interviewer. But over and above its considerable historical import, the archive of outtakes is fascinating to those interested in the cinematic memory and representation of the Holocaust, for it not only reinforces the extraordinary character of Lanzmann’s monumental film, it also provides a fascinating glimpse into his method and practice of filmmaking, which was uncompromising and disciplined in its pursuit of its aims, exacting of both its director and its interview subjects, and almost single-mindedly dedicated to its goal of disclosing the traces of the Holocaust past as they persist in the memory of its eyewitnesses.

EVENT: “The Holocaust in Literature and Film: Revisiting Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah”

Sue Vice, University of Sheffield - Holocaust Memorial Lecture

Monday, November 5, 2018, 5 pm

Washington University, Umrath Lounge in Umrath Hall