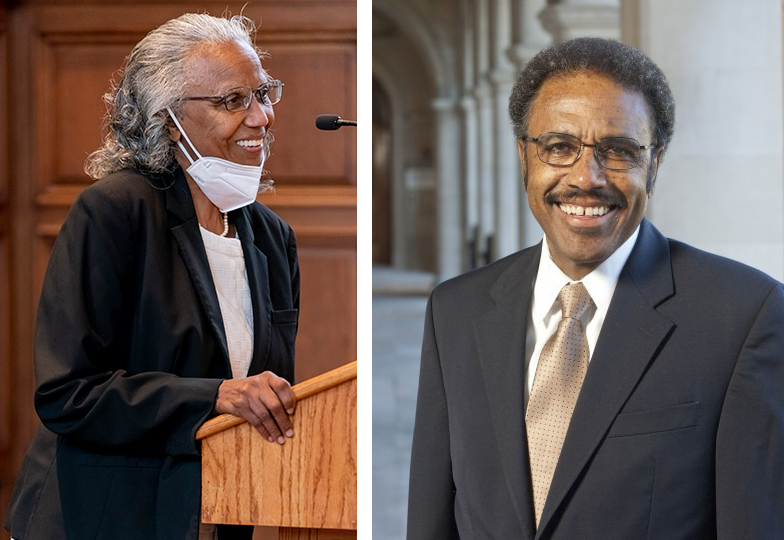

Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters and two-time director-chair of the Department of African and African-American Studies, delivers the Center for the Humanities’ 10th annual James E. McLeod Memorial Lecture, September 30, 2021. Video and text available below.

Click on the image above to watch a live recording of Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters and two-time director-chair of the Department of African and African-American Studies, as he delivers the Center for the Humanities’ 10th annual James E. McLeod Memorial Lecture, September 30, 2021.

1. As It Was in the Beginning

Robert Williams, the first director of Black studies at Washington University, seemed the ideal person for the job. That is, he embodied the change taking place among Black people at that moment. After all, the Association of Black Collegians who organized the sit-in at Brookings Hall in December 1968 did not want simply any Black academic to run the Black Studies Program that was the primary demand of their Manifesto. It had to be a person who understood why the demand was made and what a Black studies program was supposed to accomplish.

Williams called April 4, 1968, the day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, “the precipitating event.”1 At the time, he was living in San Francisco and working for National Institute of Mental Health. He was, by his own account, highly successful: “38 years old and in excellent health, married for 20 years, father of 8 children, property owner, holder of three educational degrees (bachelor’s from Philander Smith at Little Rock, master’s in educational psychology from Wayne State University, Detroit, and a doctorate in clinical psychology from Washington University in St. Louis) and earning over $20,000 a year.

“I was, however, an individualist — still a Negro. I spoke ‘Standard English,’ tried desperately not to split a verb, taught my children proper grammar and corrected them so that they would never split an infinitive. I lived in the ‘best’ neighborhoods; I was the ‘first’ to integrate the community and my children attended the ‘best’ schools. But these ‘firsts’ and ‘bests’ did not instill in me a sense of Black Pride. In fact, they created internal conflict.”2

Then, he adopted the “natural hairstyle” and grew a beard. He read all the Black books he could get his hands on. He left the National Institute of Mental Health. In September 1968, he helped to form the Association of Black Psychologists. He became a Black psychologist instead of a clinical psychologist, hanging out with other Black psychologists: “In our meetings we were doing things in a ‘natural’ way for me.” He liked the way he was changing.3

In late 1969, he wrote an article where he introduced his BITCH test (Black Intelligence Test of Cultural Homogeneity). He used the word “bitch” in the sense of complaining about something, in other words, as a synonym for “protest.” Fighting standardized intelligence and psychological testing became his mission. “Since I had almost been a testing casualty, this was the perfect cause for me. I had already been miscounseled in 1945 by a White counselor in Little Rock, the one who told me that I had an I.Q. of 82, and not to go to college.”4

Clearly, Williams was hired to become the first director of the Black Studies Program, because, having earned his PhD at Washington U, people here knew him. However much he may have changed, there had to be a level of confidence in his competence and his skill as an academic. Moreover, he was tenurable, something he rightly insisted that he wanted before he would take the job. But the change Williams was experiencing meant he was an emblem of the redefinition that Black people were undergoing, that the demand for Black studies at the White university was meant to further. Williams had strenuously, heroically recreated himself through an act of political consciousness and political will. He had ceased being a Negro and had become a Black person. The change was psychological even more than it was political. Or let us say for Black people at the end of the 1960s, the political was the psychological or the psychological was the political. The idea was to free oneself from what White people thought you were and from White people wanted or expected you to be. No Black skin, White mask. It was the era of the natural hairstyle, “Black is Beautiful,” Black Power and self-determination for Black communities, anti-colonialism, dashikis, Blaxploitation movies where the White man got his just deserts. Kwanzaa, the Black holiday, and the Kawaida or Black Value System were created in the mid 1960s. It is hardly surprising that Williams’ Black Psychology course was by far the most popular the Black Studies Program would offer.

The fact that demand for Black studies was led by Black students is also key: Remember that the 1968 Olympic boycott movement was mostly made up of Black college students who constitute the major portion of Black amateur athletes; the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee was one of the major civil rights organizations of the 1960s and eventually became one of the most radical; it was Stokely Carmichael, the chairman of the group from 1966 to 1967, who sent out the call for Black college students to form Black Student Unions on their college campuses such as the one at Washington University that took over Brookings and demanded a Black studies program; Huey Newton and Bobby Seale began their organizing for Black self-defense in Oakland with Black college students. Black students at HBCUs led the sit-in movement in 1960. But even earlier Black students had organized in the 1920s and 1930s to replace paternalistic, infantilizing White HBCU presidents with Blacks.

Black studies was about getting nearer to the truth by unsettling previous claims to the truth. Black studies was meant to blow up the world as we knew it.

Williams’ transformation matched the temper of Black students of that moment. For Williams’ transformation was not just about the creation of a new identity, or about the visibility of Blackness. Nor was it devoted solely to making legible an overdue conversion experience. It was about de-centering the claims of Whiteness in the world as the normal state of the world. As Black novelist/essayist Albert Murray wrote in the late 1960s, Black students “expect to find in the courses they are demanding historical clues to the pathological condition of white Americans.”5 The Black studies movement was about making the pathology of Whiteness visible and legible. It was about exposing not just the history of the miseducation of Blacks but exposing and correcting the miseducation of America itself. In the history of Black Americans, Black studies programs were not a goal as much as they were part of a process, one of many cloths being used to clean a mirror or a window. Black studies was about getting nearer to the truth by unsettling previous claims to the truth. Black studies was meant to blow up the world as we knew it.

Alas, establishing a Black studies program did not end the problems of Blacks on the Washington University campus, although it may have ameliorated some of them. But it did make the nature of these problems clearer.

2. Is Now and Ever Shall Be

In a memorandum sent to Chancellor William Danforth dated April 26, 1973, Robert Williams, the director of the Black Studies Program, requested that the program, then three years old, be made a department. He wrote, in part:

Recently, we had a problem which brought this issue [of departmental status] to [the] surface even more so. We were looking for a faculty person in literature. We had located a person who was interested in coming to the University on a joint appointment basis. When this issue was discussed with the English Department, the Departmental Chairman was quite negative and unreceptive to the notion of a joint appointment. His decision virtually eliminated our opportunity to attract that particular individual. Not only were we having difficulty in recruiting because of the tenure issue, we also faced the possibility of not ever being able to obtain tenure for a person in literature. The English Department claimed that it was at a ceiling with twenty tenured members in that department and that they have called a moratorium on future tenure appointments. Thus, we cannot successfully recruit a top quality person for two reasons: a) because of disagreement in perceptions of what constitutes quality Black people, and b) the matter of tenure.6

The memo reveals that there were serious concerns within the Black Studies Program of being able to retain the faculty it wanted. If Black studies could not create tenure dossiers to justify the scholarship of the people it hired and if other departments would not partner with it in supporting its efforts to hire faculty, how could it exist? It might very well be argued by university administrators that Black studies was structured exactly like any other area studies program at the university. What Black studies argued was that it had to be an exception to that structure because it was Black studies, because of how it came into existence, because of its mission to correct the institutional racism of the university. The university was giving every indication that it did not trust the judgments of Black studies and in fact was wary of Black studies’ mission. Many Whites at the university at this time did not think of Black studies as an academic field but rather as a problem eliminator, something that was good for race relations, or even worse as a kind of academic racial cult, a place where Blacks hang out and ruminate on the mysteries and injustices of being Black. So, the Black Studies Program had an uneasy relationship with the university that created it but the relationship was remarkably civil.

A tenure-track appointment in literature in the Black Studies Program would finally be made in January 1982 when I was hired, nine years after Williams wrote his memo and was no longer the director. It was not a joint appointment. I was solely in Black studies. My presence did not solve any problems for Black studies. It can be said that my presence did ultimately resolve an issue but not in Black studies’ favor.

It is commonly asked of applicants during a job interview why they want the job. I answered that I had always wanted to work in a Black studies program. This was not exactly true. I was willing to work in a Black studies program but had not aspired to do so. I wanted the job for a practical, prosaic reason: It started in January 1982 and not the following fall. My youngest daughter had been born on Thanksgiving Day 1981, a few weeks after my interview here at Washington University. My health insurance only covered part of the costs of her birth. I needed a job in a hurry. I could no longer survive on a stipend. I could not afford to go to the MLA convention, which is where English graduates like myself lined up for job interviews. The literature job in Black studies was a godsend for me. I was terribly afraid that I would not get the job because my training was insufficiently steeped in Black studies. Alas, the old saying is true: Sometimes it is better to be lucky than good. I was lucky.

I knew nothing about tenure except it was something I was supposed to get if I was good enough after a probationary period of five years. I did learn soon after I arrived at Washington U that no one in Black studies had gotten it, that is, gotten promoted with tenure. The dean of Arts and Sciences told me that a special committee would be appointed when my turn for tenure arrived, made up of people in Black studies and the English department. As I thought about this, I was puzzled. Only tenured people could pass judgment on whether someone could be promoted with tenure. The only person I knew who was tenured in Black studies was Robert Williams, a psychologist, not a literature person. Having people in the English department judge me was fine, except I had no joint appointment in the English department. I was 100% in Black studies. Why should people in the English department judge whether I should be tenured in a Black studies program? If I had to please the English department, shouldn’t I be in the English department in some form or fashion? The dean informed me that Black studies was considered an area studies program, and this is why someone could be solely appointed in it. But it was not a department, so it could not preside over my tenure case. As I mentioned above, I did not solve any problems for Black studies when I was hired. I seemed only to have encountered a few for myself.

I chose not to think about any of this for two reasons: 1) I did not think I would be working at Washington U when it was time for me to go up for tenure; and 2) no one thought I stood any chance of getting tenured because no one appointed in Black studies had been tenured. Why worry about something that you were not going to get? Clyde Ruffin, the theater professor for Black studies, was denied tenure shortly after I arrived. He did not produce enough scholarship, so the dean’s committee on promotions gave him the axe. But it seemed that Black studies was not particularly interested in someone having this position who wrote scholarship, preferring someone who did productions. I am not sure where performing arts stood on this matter, but it too was a program then, jointly presenting the case with Black studies. There seemed to be such miscommunication or misunderstanding here about expectations concerning Ruffin that there was no chance of his being tenured no matter how brilliant a director he may have been. Black studies faculty were upset with this decision, for they felt they were being denied the right to define their own pedagogical and programmatic needs. This is where and when I entered the program.

The director of Black studies when I arrived was an assistant professor of history named Gerald Patton. I did not think he could mentor me much as we were both assistant professors. We were both in the same boat. He was just a few years ahead of me. In a couple of years, he too would be denied tenure. He even wrote a book called War and Race: The Black Officer in the American Military, 1915-1941 that was published in 1981. I read his book to learn how to get tenure in Black studies since everyone said I had to write one, as that was the trick. The title had a colon, that seemed legit for an academic book. It had copious footnotes, that seemed legit for an academic book. It was on a specialized topic of interest to a small number of people, that seemed legit for an academic book. It had all the trappings of what I was supposed to do and it seemed to have added some questions to the debate about Blacks and military. What more was an academic book supposed to do? But I learned from his example that writing a book was no academic equivalent of a magic bullet for getting tenure. To paraphrase a movie title, publishing scholars also die, especially if they are in Black studies.

Patton’s biggest impact on the program was that, with the faculty’s approval, he changed the name of it from Black studies to African and Afro-American studies in 1985 to emphasize our new diasporic reach with the hire of African historian Michael Gomez, who would become the director after Patton’s departure. He would not be tenured here either. The name change was not insignificant. Black studies was now known as AFAS, and it was important at the time to claim specific fields rather than a race or the ideological state of a race. It was part of the sea change that was to hit Black studies nationally in the 1980s when the quest for respectability and mainstream acceptance clashed with a desire to move further away from western models of scholarly validation.

The two professors I knew best — Robert Watson, who taught the popular Intro to Black Studies, and Robert Johnson, a sociology professor who had been a student here and helped to write the Black Manifesto of 1968 that led to the formation of the Black Studies — were also both denied tenure. Their denials were a big issue with Black students and were mentioned in the Black Manifesto of 1983. Indeed, of the eight listed concerns of the 1983 Manifesto, the first four were directly related to the Black Studies Program, including a demand that it be made a department, 10 years after Williams’ initial demand for departmental status. Nothing had changed in the interim.

I told Rob Johnson that I was not much interested in turning my long, dumb, boring dissertation into a slightly less long, slightly less dumb, slightly less boring book. I told him I wanted to write essays, nothing else. He encouraged me, telling me I would feel better if I was denied tenure having done what I wanted instead of what I thought would please other people but not myself. That was a comfort to know. What did I have to lose? Johnson also told me never to win a teaching award. No Black person winning a teaching award was ever taken seriously as a scholar, he said.

It was also something of a comfort to know that when I got bounced, I would at least be in good company, upholding a tradition of sorts. So many people were tossed, why not me? By the mid 1980s, I believe most people thought that the Black Studies Program would be closed. How could it be otherwise when no one connected with it was being tenured? How could it maintain itself as a major?

I met James McLeod for the second time when he accompanied Chancellor Danforth on his annual visit to the Black studies offices. I doubt if the Chancellor annually visited every academic unit of the university, but I suppose Black studies required his special attention. The visits were pleasant. The chancellor seemed interested and concerned. James McLeod seemed a nice man. I first met James at the job talk I gave in November 1981. I was not sure why he came to the job talk. He was not in Black studies. He was or had been an assistant professor in the German department. It was a long, dumb, and boring talk. He was kind about it, indeed, impressed. He came to all my long, dumb, and boring talks during my early years here. I thought he was a glutton for punishment. He was courtly in a way that certain educated Southern Black men are. He seemed to think I had possibilities. He was assistant to the chancellor at that time and I was impressed with his possibilities as well.

As time passed, I thought of him more and more as the university’s version of Daniel. I thought James could not only interpret the dreams of the people in Brookings but that he could actually tell them what they had dreamed. Like Daniel was always true to himself as a Jew, James always seemed true to himself as a Black person, even as he worked among the Whites, even though he did nothing that drew attention to the fact that he was Black. I was impressed by this because it is difficult to do. One can be loyal to many things serially that seem to be antagonistic to each other, but it is quite an act of the imagination, a real act of ingenuity, to be loyal to many things simultaneously that are antagonistic to each other. He had the uncanny ability to make antagonistic interests lie down together like lambs and lions do in heaven. He was the type of Black person who is called a bridge.

There is a line in a Bill Withers song that goes: The most you can ever do is the best you can. It was an expression I sometimes heard as a child among the older Black people I was around. It was an ironical expression that told you to know your limits but to exceed them as a moral imperative. I would see James on campus every now and again and think of that expression.

I did not see James often on campus as he was an administrator working in Brookings and I was a faculty member teaching class and trying to write essays. Two things would happen to change that: First, after returning from a two-year postdoctoral leave, a new dean of the faculty changed my appointment so that I was now in the English department officially and was only secondarily in Black studies, or AFAS as it had become. I had to struggle to stay connected to AFAS. Second, James McLeod would become the director of AFAS in 1987.

3. World Without End

There is something important to understand about Black studies: First, Blacks studied themselves before Black studies emerged at the White university. Black Americans wrote histories of themselves, wrote accounts of Africa and Haiti, as far back as the mid 19th century. Second, there was a well-established field called Negro studies that included such well-known people as W.E.B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, Alain Locke, Abram Harris, Ralph Bunche, John Hope Franklin, Arturo Schomburg, and many others. In fact, without these earlier scholars, both amateur and professional, Black studies could never have come into existence. Despite the fact that some associated with Black studies, such as Maulana Ron Karenga, repudiated Negro studies as insufficiently revolutionary, insufficiently Black nationalist, insufficiently Marxist, Negro studies existed under more trying circumstances than Black studies ever did; it was virtually the only field that Blacks could establish themselves as scholars. It was the only place where Blacks were not viciously assaulted and insulted by White scholars. It was a safe space, to use a current expression, and was not Black studies at the White university demanded by Blacks for the same reason, as a safe space? In the age of segregation, as John Hope Franklin pointed out, it was difficult for Negro scholars to get lunch, let alone access archives, especially in the South. Negro studies was heroic work. Didn’t these Negro scholars have heavy teaching loads at Negro colleges and far less time to be scholars? Didn’t these Negro scholars have far less access to grants and university research funds than their White counterparts? But, as John Hope Franklin argued, because “many of the whites conceded that Negroes had peculiar talents that fitted them to study themselves and their problems,”7 Negro studies became another form of Jim Crowism. Negroes were now relegated to the study of themselves. Then, by the late 1960s, Negro studies was replaced by Black studies. Was Black studies a form of empowerment or a form of marginalization? Was it liberation from Eurocentrism or an ethnic trap? Did Black studies supersede Negro studies or merely reinvent it? In either case, weren’t Black and Negro scholars driven to come to the defense of their race? Black people and Negroes have something to say to each other. After all, as I told my daughters, all those Black people who emerged in the 1960s were the sons and daughters of Negroes.

When James McLeod became the director of AFAS, there was a feeling in some quarters that the program was going to be shut down. No one associated with it had been promoted with tenure and the loss of faculty was beginning to grind down morale. The junior faculty like me who were left had been farmed out to established departments and told to make the grade there. I felt as if AFAS was being abandoned. In fact, the dispersal of the few junior faculty who were left convinced me that AFAS was not long for this world. There was the smell of dysfunction and demise about the whole enterprise. Moreover, although this was not the first time a full-time administrator was placed in charge of the program, James was not even in the field of Black studies. [The other administrator, Horace Mitchell, had been.] This felt like a long goodbye.

So, I asked James outright if he was overseeing the end of the program. It was naïve that I expected an honest answer from an administrator, but James struck me as a man of integrity. I knew he would tell me the truth. He was, after all, Washington U’s version of Daniel. He told me he was not there to shut down the program, and that he would never have taken the job if he had been asked to do so. I believed him. He also told me that he thought I was essential to the future of AFAS, and he wanted to do everything he could to support me. I did not think I had much of a future at Washington University, let alone in AFAS. I thought he was simply being nice.

I was wrong. James became Santa Claus for me. Any day I wanted could be Christmas. If I wanted some new-fangled computer, it was mine. If I wanted to do a conference, there was money for it, no concern about cost. If I wanted to travel somewhere for some such reason, there was money for it. I could do whatever I wanted, could ask for whatever I wanted. I once had the perverse thought that if I wanted to take over the AFAS office next to mine that James would have had the adjoining wall knocked down, kicked my neighbor out, and given me both offices. Anything that supported my work, my mere presence as a professor, was mine for the asking. I understood that James was doing this, in part, to maintain my allegiance to the program as there were so few tenure-stream faculty left in AFAS. But also, he wanted to show that he personally was invested in my success, that he believed in my possibilities. I cannot tell how much that meant to me! Here was someone who was looking out for me. When you are junior person, that means the world to you!

But how James treated me was irrelevant to his effect on AFAS on the whole. Because James was not in the field, he had no ideological stake in it. “Canon building” versus “canons are elitist and oppressive”; “Black womanist and queer transformation of Black culture” versus “Save the heterosexual Black man and Black boy”; African diasporic and Afrocentricity versus Anti-essentialism and cultural pluralism. James was indifferent to all that. This turned out to be good for the program because he did not try to bend its identity in a certain way. At that time, I don’t think the program would have profited from such an effort.

In this way, he gave a beleaguered program breathing room. We junior people could think about tenure and not which side we were on in faculty meetings. In fact, James hardly ever held a faculty meeting. It was a relief because, for James, everything had value. James was on everyone’s side. For him, Black studies was capacious. It contained multitudes. It was bigger than the sum of its disagreements. James constantly preached that AFAS was for everyone. And we attracted a more motley collection of students under James than we had before. He did not see it as an academic unit or a listing of courses or even a major but rather as an experience, as much for the faculty as it was for the students. During those years under James’ leadership, AFAS felt like an experiment. Try something, he seemed to say to us, it might work and if it doesn’t work, the failure will be good for you because Black people ought not fear and knuckle under to failure. James taught us all something important, crucially important, in those years: Do not fear the program’s uncertainty; rather, embrace it as a way for you to grow, as a way for you to get nearer to something. Being Black itself is the act of wrenching assurance from uncertainty.

James talked to students, met with them, incessantly. AFAS was always a student friendly place, but James took it to another level. Our relationship with Student Educational Services, which provided academic support largely for Black students, was strong but during James’s term of leadership, it seemed closer than ever. At times, I felt we were a branch of SES. I was not sure if I liked this, but James felt we had to show complete commitment to our students. And so, we did. “Students come to us for something they cannot get from other units,” he would say. “We should give them what they seek and what they need.” Robert Williams understood from the outset that Black studies was not merely about training the minds of students; it was about winning the hearts and minds of students. James saw this too. After all, protesting students were the reason we existed at all. And the presence of their pressure, of their manifestoes, was one of the reasons why we continued to exist.

It was not that James reinvented Black studies or AFAS; he simply re-enforced its virtues and its strengths. He reminded us of what we were good at and that we made the university a better place. During one of my moments of self-doubt, he told me, “You’re as good as the best thing you’ve ever done.” I guess he told us all that in one way or another. And for many of us, maybe the best thing we had ever done was to teach in a Black studies program.

The entire constellation of changes James had a hand in during his career: the Ervin Scholars Program, the Mellon-May Program, the acquisition of the Henry Hampton Film Archive, the restructuring of university advising, expanding study abroad, establishing resident faculty fellows — I would like to think that his experience as director of AFAS inspired these accomplishments. Certainly, what he accomplished as an administrator at Washington University stabilized and enriched AFAS far more than any other single director could have done, no matter how good some of these directors were and several of them were incredibly good. The conflict between university administration and AFAS was that the university’s primary concern was respectability; AFAS’ primary concern was agency and autonomy. For the university, respectability was the goal. For AFAS, respectability was a disagreeable but necessary tactic, never a goal. The bridge between these antagonistic views was James McLeod.

The last time I saw James, a few weeks before he died, we chatted a bit on a hot afternoon. I knew he was terminally ill but I asked him how he was, then regretted it as soon as I asked. He said something to the effect of feeling right with God, with his savior. I was surprised because during all the years I had known him he never spoke of God or said anything religious to me. He didn’t seem to mind that I asked how he felt. We spoke a little more and then parted. “Still all my song shall be/Nearer, my God, to Thee.” That is a good hymn for a dying person to think of or for a person who is not dying to think about with the dying.

There were three things I learned from James McLeod. First, that it is important to listen to people, particularly people you do not want to listen to. Listening is a demonstration of patience and a show of regard for another person. It is also a demonstration of resolve. It is a sign of strength, not weakness. Second, I learned that reaching the goal is less important than how well it is sought. That is the key. One has to be guided by the idea of getting nearer, not the goal, but in how well and with how much integrity one can have in pursuing the goal. For James, understanding a goal and re-understanding it was, in a sense, the way to achieve it.

The third thing I learned from James was that singer Bill Withers and the older Black adults who were around me when I was a child were right: The most you can ever do is the best you can. And the most that you ought to do is the best you can.

Here endeth the lesson.

Endnotes

1. Robert L. Williams, “The Collective Black Mind: An African Centric Theory of Black Personality,” (St. Louis, Robert L. Williams, 1981), 2.

2. Ibid, 2.

3. Ibid, 3-4.

4. Ibid, 4-5.

5. Albert Murray, The Omni-Americans: Black Experience and American Culture (New York: Random House, 1983), originally published in 1970, 204.

6. Memorandum included in Manifesto of Black Concerns and Issues, Prepared by The Association of Black Students, May 1983, page 24, (Memorandum, in total, 4 pages long), Washington University Archives, Black Manifesto Collection.

7. “The Dilemma of the American Negro Scholar” in John Hope Franklin, Race and History: Selected Essays 1938-1988 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 301.