Deborah Thurman is a Lynne Cooper Harvey Fellow in American Culture Studies and PhD candidate in the Department of English.

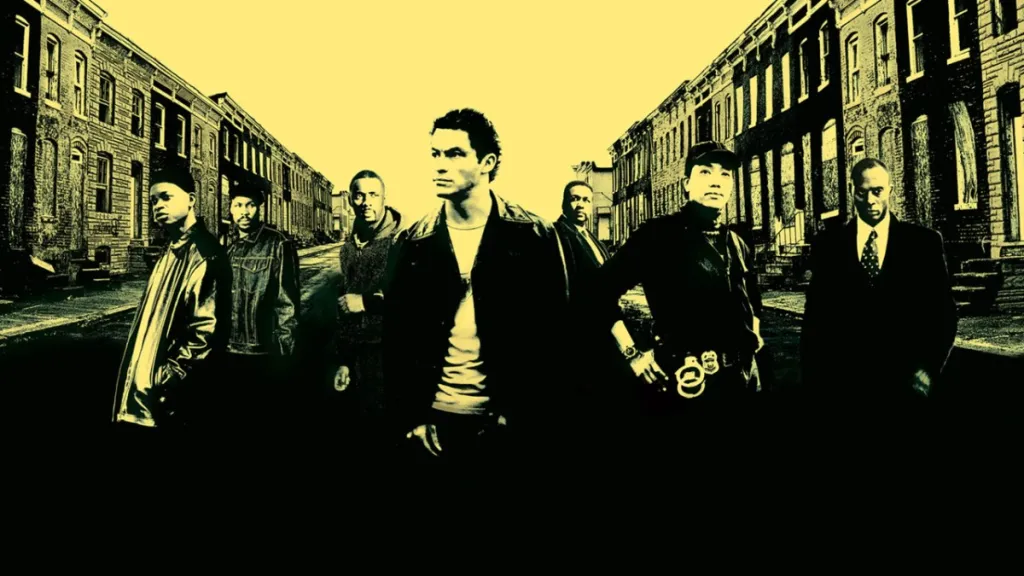

While the disrupters and innovators of the world get a lot of attention, literature and culture scholar Caroline Levine has focused on the often-overlooked patterns, repetitions, and routines that keep things running—in culture as well as institutions. In advance of her keynote lecture at the Faculty Book Celebration on February 21, Levine gave an interview to PhD candidate Deborah Thurman, who asked Levine about her analysis of social and artistic forms, defense of repetitive structures, and how she found support in sources ranging from Victorian literature to The Wire.

Your most recent book, Forms, thinks about structures that organize literature, like genre and rhyme, alongside structures that organize people, like architecture and school systems. What first inspired you to compare the two?

My first two books led me to develop a theory of aesthetic and social forms. My first book made an argument about suspense in the nineteenth-century novel. Rather than just a cheap marketing technique, I argued, suspense fiction actually shared a crucial structure with the scientific experiment: in both cases, you are faced with a mystery—or a hypothesis—and then expected to wait, suspended, to see whether your hypothesis fits the truth. Victorian scientists were determined to persuade public audiences that the most important element of the scientific method was self-restraint: you couldn’t assume that you knew all the answers but had to test your guesses and wait for the answers.

My second book seems at first like a totally different project. I was investigating controversies over art works in Britain and the U.S. in the twentieth century and tracking debates about public art, obscenity, copyright, and propaganda. To my surprise, in every case, I came across a common structural tension: communities objected to artists for not pleasing the public and rejected art in the name of democratic majorities, while artists justified their work as deliberately unpopular, valuable for its challenges to mainstream tastes and values. I ended up thinking a lot about how forms can be shared across domains: the same form shaping scientific experiments and popular novels, or the same logic about majority rule animating both artists and their antagonists. This got me thinking about whether artistic forms always operate on their own separate plane, or whether they can be brought into relation to other forms, all helping to make the social world what it is. My book Forms argued that artistic and social forms have a lot in common, and that we can use the same tools to analyze them.

You tend to engage with a wide-ranging archive, from nineteenth-century novels to the TV show The Wire. How do you choose the best examples to illustrate the concepts you want to discuss? Or do you start with the object—that is, “I really want to write about The Wire”—and work from there?

This is a great question! Somewhere along the way I realized that if you have a transhistorical theory of how the world works, then logically any example should work. This made the selection hard—and in some ways arbitrary. I knew Victorian literature and culture best because this was my field of training, so lots of my examples come from nineteenth-century Britain, but I deliberately looked and browsed and listened for examples far from my own period of specialization. I wanted to make sure I included premodern and non-European forms, for example, to test the validity of my theory. The Wire was an unusual case because I had been teaching it for years and had the intuition that it was saying something true about the world that I wasn’t seeing in any theory, so it was partly by working through the text that I developed and sharpened my own theoretical contribution.

Your work mounts a defense of repetitive patterns against a scholarly tendency to celebrate the unique and the disruptive. Why do you think scholars tend to be suspicious of repetition?

Modernity is in thrall to innovation. Think about how we tell the history of art and literature and technology all as stories of breaks and disruptions. We celebrate the innovators as heroes. At the same time, modernity ushered in one of the most terrifying kinds of repetition: the deathly routines of factory work, which dehumanize the worker and some say turn her into a machine. For many theorists since the nineteenth century, art alone is the force that can break through the deadening routines of modern existence. But what about maintenance—the work of keeping up our spaces, feeding our bodies, and preserving infrastructures? These are not heroic, not creative activities, but no human society can do without this labor. I think it’s time to revalue repetition for the sake of sustainability.

The project of revaluing repetition has some forebears within second-wave feminism. I’m thinking about people like Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who has worked since the late 1960s to reframe acts of maintenance (e.g., sweeping the floor) as a kind of art (“floor paintings”).

I love Ukeles and have just been writing about her in my newest work. Since the Romantics, the dominant strands of art and criticism have celebrated innovation and rupture, but that has allowed us to overlook or dismiss so much of the work of maintaining collective life—preparing food, taking out the garbage, tending to the sick, to infants, and the elderly—which has often fallen to women. If women’s work is so repetitive that it can’t count as creative or heroic, is that a problem with women’s work or with our aesthetic values? I’m writing now about sustainability, and I think that it’s crucial to revalue lots of repetitive labor as essential to sustaining life. For this I’m turning to Ukeles and bell hooks and Susan Fraiman’s new work—all feminist arguments for the value of routine maintenance.

Can you give us a preview of some of the topics your new book will discuss?

In Forms I focused on how forms destabilize each other, and I didn’t think there about how some forms reinforce one another in stable and predictable formations that endure over time. Now I am thinking about how some of the forms we have most often dismissed across the aesthetic humanities—narrative endings, regular rhythms and rhymes, popular songs, formulaic plots—might offer us resources for building sustainable communities. I have a chapter on building robust leftist political organizations for the long term. And I have chapters on routine and infrastructure—both forms that I think will be crucial for a sustainable planet.