Alongside her role as internship coordinator for the Center for the Humanities’ Sumner StudioLab, Crystal Payne is a Graduate Student Fellow in the humanities center, a PhD candidate in the Department of English and a Lynne Cooper Harvey Fellow in American Culture Studies. Her research focuses on Caribbean literature, postcolonial studies, global anglophone literature, migration studies and hemispheric American studies.

The soccer game ends: It’s a loss, but our team fought hard. My partner and I weave through the large crowds pushing their way towards the exits, and as the night air hits us, the crowd makes a beeline for the Metro. Barely edging them out, we find ourselves, luckily, right in front of a train door, and we quickly secure seats next to each other in the fourth car as the crowd keeps pouring in. The train was quiet when we entered, filled with weary people trying to make their way home. As the last group of soccer fans filters in, however, their voices overpower everything. They talk and laugh loudly, decked in their pink and blue jerseys that symbolize their support of the local team. While the Metro is a lifeline to some, many of the soccer fans, like me, use it only to attend sport games more conveniently.

As the conversations grow noisier, one of the train travelers who preceded us begins playing music loudly. It is the gritty kind of rap music, and the beat is catchy. A lady sitting in front of us turns a little to look at the man a few rows behind us who just turned on his speaker. Showing her approval, she nods and does a little dance in her seat, her red and black braids swinging to and fro. A white soccer fan who was loudly speaking a few moments ago scrutinizes the Black man with the speaker, annoyed. Caught between my desire to respect public space and this overt public act of resistance against the disrupters of the peace, I look on at the conflict, now an unspoken and racialized debate about who owns the space and which version of public behavior is acceptable.

In fact, this Metro conflict is part of a longer framework of division and divisiveness in St. Louis. The city is divided along lines of class and race; white people move in and displace black communities — gentrification — locking them out through the rising prices of rent. Black residents move in, and white people and businesses leave — white flight. North St. Louis, predominantly Black and lower-class, is coded as a dangerous, crime-ridden place. “Stay close to the university campus,” someone told me when I first moved to St. Louis.

Yet, as I drive into The Ville neighborhood in North St. Louis weekly, past the invisible border of the Delmar Loop, what I see beyond the buildings are regular people living their lives. Crime exists. Life, too. Nonprofits and community groups and development workshops. People who want to save the trees and improve their parks. Kids who go to Sumner High School and chat with me about their lives at the Sumner StudioLab. An old black man hanging out on the corner smiles and asks, “How you doing?”

As a transplant to St. Louis, a city with numerous lines of division, I wonder where I fit as a WashU graduate student doing community engagement work in North St. Louis and as a soccer fan privileged enough to use the St. Louis Metro not for necessity but for convenience.

The battle continues between the Metro riders who were there before us and the soccer fans. The fans stare at the music-man; some of them smile and do a little jig — an olive branch, maybe — after all, despite the fraught histories, St. Louis City is diverse. A few of them give him their nastiest stink eye, not recognizing his actions as a response to theirs, and not acknowledging that just moments ago, their overpowering voices were similarly responsible for ruining the peace of the tired train riders.

A few of them give him their nastiest stink eye, not recognizing his actions as a response to theirs, and not acknowledging that just moments ago, their overpowering voices were similarly responsible for ruining the peace of the tired train riders.

“Which is right?” I ask my partner as we get off three stops later. Perhaps my identity as a Black immigrant woman makes me hyperaware of how I navigate the world: “Crack a joke; be less aggressive; smile more; make sure people know you’re not a threat.” But, like Brent Staples acknowledges in “Black Men and Public Space,” an essay I often assign my college writing students, there are people who go about public space effortlessly, like their navigation of the world is natural and uncontentious; people at ease in expecting the world to accept whichever version of themselves they show in public, because public perception of behavior and of respectability is shaped by dominant narratives.

And then there are those whose navigation of public space has been an uphill battle, fraught with judgment about their respectability and their way of existing in the world. “Enter that space,” bell hooks tells readers in “marginality as site of resistance,” because “understanding marginality as position and place of resistance is crucial for oppressed, exploited, colonized people.” Existence and resistance come in all forms, and the two are not mutually exclusive.

The man playing music inverted the original disruption caused by the loud soccer fans, as if saying, “This is what it’s like when someone is loud and inconsiderate on the Metro.” The lady with braids whoops to show she still agrees with him. The soccer fans continue to talk and the loudest among them persist in their disapproving looks.

I walk away from the station and leave the battle behind, but it stays with me, for the conflict is but a microcosm of the larger social battle between how white Americans navigate public space and how Black Americans navigate the same space, between modes of belonging and social acceptance, between “normal” public behavior and deviant ones. The battle in the Metro is a symptom of the friction of a still-divided city in a divided country in which we all share space.

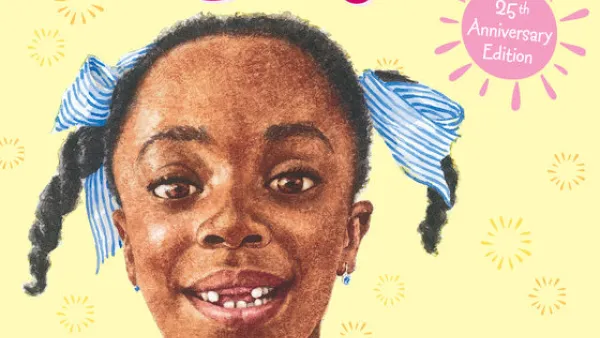

Headline image by Victor Rodriguez via Unsplash