Laurel Taylor is a PhD candidate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures and the Program in Comparative Literature. She also earned a graduate certificate from the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

My work springs from connections. Of course, all work springs from connections — the right teacher, the right friend, the right colleague — but I can point at specific moments in time and specific encounters with people that led me to my dissertation research, “Moved: Affective Bonds in Online Literary Media.” Let me paint for you a constellation — a series of bright temporal points I’ve connected with imagined lines that nonetheless resonate in my own consciousness. 2016: My MFA mentor Aron Aji tells me the time is now; I must translate poetry now no matter how much I don’t want to. 2001: My best friend Devon tells me he thinks I might like this thing called anime. 2019: A colleague makes an off-the-cuff remark that virtual objects aren’t “real.” 2002: I discover troves of illicitly scanned and translated manga online and clog our phone line as I voraciously read. 2018: An online friend I know only by a pseudonym tells me about this Chinese web novel I’ve got to check out. 2015: Chiaki Sakai, the University of Iowa’s subject librarian at the time, hands me a book called 140 ji no monogatari (Tales in 140 characters) because I need something I can translate in a rush to meet a workshop deadline.

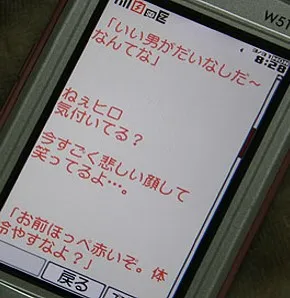

Image courtesy Laurel Taylor.

These shining points — main-sequence stars in comparison to the clouds of white and red dwarfs around them — are what first drew me to thinking about the kinds of affinities I feel for literature that is often, at least in academic circles, considered beneath study or attention — literature like Japan’s cell-phone novel. The early Internet provided a means for textual production and dissemination previously unheard of for most people, and in Japan in the early 2000s, it gave rise to the cell-phone novel, a literary form consisting of short, serialized chapters featuring colloquial prose, a preponderance of empty space, and melodramatic themes of romance, sexual assault, drug usage and numerous other soap opera-esque plotlines.

In case of point, none of the contents of cell-phone novels or the literary forms that came later are truly new. What is new and different about them is the affects produced by the technology that houses them. In the Japanese context, most people’s interactions with the internet came not through a desktop computer but rather through their flip phones. Because users were constrained by data plans that charged by the packet, most hosting platforms understood that their websites needed to focus on relatively data-light content: text blogging with very, very few images. These blogging sites allowed people to post text-based works anonymously, producing what communications scholar Tomita Hidenori calls the “intimate stranger.” Freed from the social constraints of face-to-face interaction, users were able to make more intimate and “real” portraits of their lives, and some of these portraits, which were “based on a true story,” evolved into cell-phone novels.

To carry on my astronomical analogy, cell-phone novels were the equivalent of stellar collisions. In the world prior the internet, readers could orbit writers and could even drop a small meteor or two in the form of a letter or an encounter at a signing, but those immediate connections were rare and tended to position the writer in the place of authority and intellectual dissemination. In the intimate and anonymous spaces of early 2000s blogging sites, users — primarily young women — were allowed to fall out of orbit and collide with each other. The internet collapsed the space between producer and consumer, lowering the barriers to entry and making the concept of writing for others available even to users who had never dreamed they might be writers.

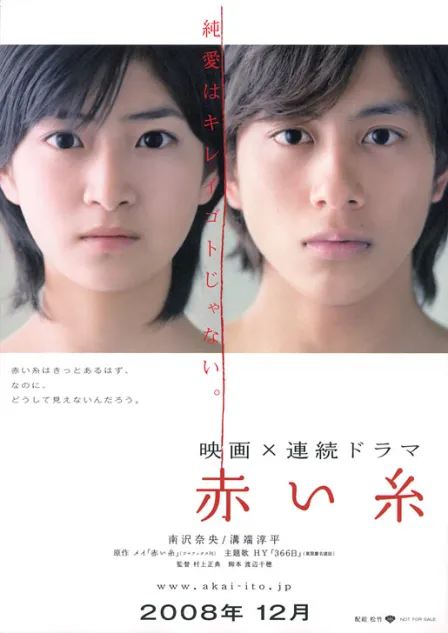

These novels became viral media sensations as reader bases primarily composed of teenage girls and young women began devouring and producing them in droves. Some of the most popular works like Koizora (Lovesky), Akai ito (Red thread) and Train Man (Densha otoko) were subsequently contracted by major publishers and media corporations, selling hundreds of thousands of copies while at the same time feeding critical roundtables about the death of literature and publishing. But, as we have seen in what cultural scholar Heekyoung Cho calls “the platformitization of culture,” corporate entities have leapt at the chance to monetize the free labor of “amateur” writers to further their own advertising and membership revenues. The literary ecosystem of the cell-phone novel and its offspring like Twitter novels and web novels has rapidly transitioned from a space affectively charged with joyful contact and reparative production to a space in which users perform affective labor in economies of anxiety.

For me, this brings me back to my own constellations of internet encounters. I too was (and still am) someone who performs this free labor, sometimes gladly, sometimes grudgingly, sometimes angrily. I serve as an editor and brainstorming partner for online friends. I publish blogs and metacommentaries. (No, I won’t be sharing my screenname; I value my position as an “intimate stranger” far too much.) I’ve participated in Japan’s Literature Free/Flea market (Bungaku furī māketto), where aspiring young writers (as well as some professional writers — Akutagawa-prize winning author Li Kotomi was in attendance in November of 2021) pay predatory self-publishing agencies for hard-copies of works ranging from literary fiction to pornography to poetry to communist manifestos.

A great deal of scholarly work has been done on the economies of these born-online works, but often their contents are an afterthought. For me, however, I want to think through the appeal of these works in terms of both their content and the social networks they weave. Many of the most representative cell-phone novels are charged with nostalgia, hope, soothing (iyashi) and new conceptions of “reality” that point toward a desire to imagine a better future in the face of economic stagnation. These affects are products not only of the writing itself but also of the anonymous author’s fluid position as writer, friend and blank face upon which a reader can impose herself. The very borders of the individual dissolve more readily and easily than ever in the pixels and bits of online stellar collision. These works of feeling and “texture” (to borrow essayist Sugiura Yumiko’s word), pass freely and easily through the collapsed spaces and times of the internet, inviting users to join in a project of collective production which, in spite of its fleeing pleasure and exploitative apparatus, nonetheless feels as powerful as a supernova.