Taylor Thomas is a sophomore and former Center for the Humanities Banned Books Undergraduate Research Fellow. She is pursuing a double major in anthropology and global studies. Her research during the fellowship focused on the psychological dimensions of identity formation within Black and African-American adolescents, concerning contemporary literary censorship.

I remember the first picture book I read. The words were not what captured my attention; it was the image on the thick, laminated cover that was memorable: a girl with a huge gap-toothed smile, her hair in two luscious, black braids with bows at the base of each. She was just like me, a young Black American girl, interacting with her surroundings as I did. While I might be dating myself when I name the title, the Amazing Grace picture books filled my shelves because of my deep connection with the illustrated girl who filled the pages. Growing up in an area where I was the only Black student in my elementary class, these books allowed me to feel seen and represented.

So, in the late months of 2024, when news sources became flooded with reports of educational policies that banned these and similar books, I took it personally. Through the Center for the Humanities’ Banned Books Fellowship the following spring, I began research in which I asked questions about the effects of literary censorship on African-American and Black American adolescents’ identity formation. These banned literary pieces disproportionately affected (auto)biographical, historical and contemporary Black narratives. Thinking back to my childhood and the importance that literature and knowledge acquisition had in my life, I had to ask: What happens when Black American children do not have access to literary representation and how does this lack of representation affect their identity formation?

Anthropologists often interpret identity as an ever-changing, flexible sense of oneself that an individual curates based on the connections that they have forged in their society. Moreover, identity is influenced by all parts of a person's life. Thus, when seeing books like Amazing Grace, on my bookshelf as a child, I found comfort within being myself. Grace’s hair, smile, and family that mimicked my life allowed me to build an identity outside of my predominantly white school and the cultural norms that came with that scene. Similarly to myself, Black American children must look far and wide to find pieces of their culture to properly and fully form their identity.

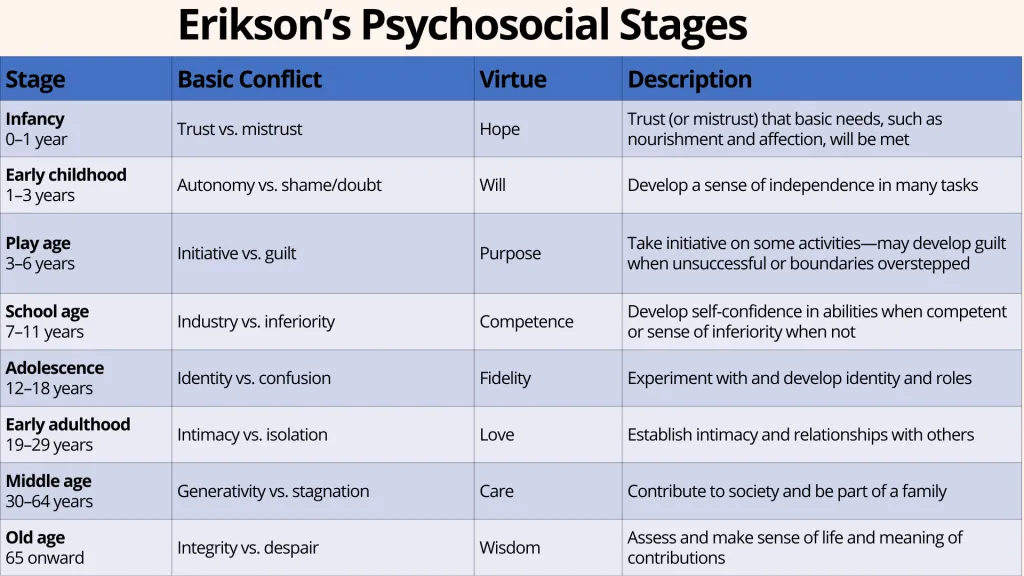

Foundational child psychoanalyst Erik Erikson’s theory on psychological development provided the theoretical framework for my research. Erikson states that identity formation occurs between the ages of 12 and 18. Without a fulfilled sense of identity, one will feel lost, floundering in a state of identity infidelity. “Identity infidelity” occurs when an individual’s values are everchanging, instead of having a set of fundamental, core values. Erikson’s chart allowed me to narrow down my research to this age group. Next, I looked to libraries and school-centered literature groups in St. Louis to begin asking questions.

I interviewed many St. Louisans to understand the real-world implications of literary censorship on Black American adolescents: librarians, children’s books specialists, a child studies scholar and a scholar of African-American history. All these discussions allowed me to learn not only about my research at hand but about the effects of policy on educational systems.

Collectively, they described literary censorship as an act that not only severs a connection between individual and community, skewing identity formation, but also prompting disdain for a certain identity within adolescents. Interviewees spoke about how mirror books — books that “mirror” a reader’s image, personality, life, etc. — allow students to see themselves in books and find joy in reading. This sense of connection is called literary self-insertion. Without this type of connection, students affected by book banning (disproportionately Black American children) begin to turn away from reading and thus education because of the feeling of educational isolation within their identity. This type of disconnect disassociates Blackness from education and academia and correlates Black identity with negative connotations of shame and forbidden narratives.

With these effects in mind, I ask that we all begin to look at literary censorship with a more critical eye. Yes, these policies remove titles from bookshelves; they create difficulties for librarians and schoolteachers; they silence narratives. But that is not the end of the story. Literary censorship means cultural disenfranchisement. When young Black American children aren’t allowed access to this important resource for identity formation, they are left with only society’s definition of Blackness. As the Black activist and poet Audre Lorde put it, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”