Bonnie Pang is a PhD student in the Department of English and a graduate student researcher with the Global Comparative Humanities Working Group.

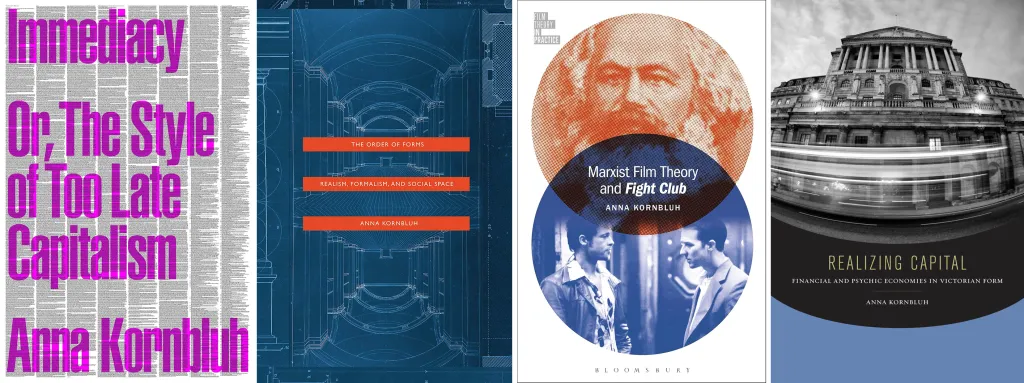

Anna Kornbluh is professor and associate head of the Department of English at University of Illinois, Chicago. As a scholar, she combines an incredibly perceptive eye with an unwavering belief in the power of literature and literary criticism to not just draw from reality but to envision new ways in which we may order it. Formalist and Marxist approaches play a consistently central role in all four of her insightful books, and through careful analyses of literary structures, she works to reframe form and boundedness as serving not as limitation but offering space for productive, collective construction.

Kornbluh recently visited WashU to give a lecture on her upcoming book on the uses of good enough, “mid” art. She also talked with English PhD student Bonnie Pang about her most recent book, Immediacy, or the Style of Late Capitalism (2024), how contemporary culture has become enamored of the fast and the instantaneous, as well as what the future of cultural production might hold. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’d like to begin with your most recent book, Immediacy, or the Style of Late Capitalism. In it, you talk about how we have become too obsessed with transparency and immediate intimacy. Intriguingly, you were writing on this topic during the pandemic when social distance was mandated. Five years on, do you think the pandemic changed our relationship with immediacy?

When you have a catastrophic break like that, a catastrophic disintegration of social relations and catastrophic abandonment by the state, that can make people want genuine relationships. Immediacy promises that kind of intimacy, that kind of instant connection, but it’s very cheapened. There’s a way you could see the extreme circumstances of the pandemic and the isolation during the pandemic as fomenting simultaneously more desire for this style.

Moreover, I think the intolerance of representation was actually fueled by the political exigencies of the pandemic. Things like our way of understanding the connection between extrajudicial violence, state abandonment and the need for real collective action. Our way of understanding that when it came to the cultural arena was extremely impoverished, with a demand for mirroring that emanated into self-authentic, self-authored representation instead of a demand for institutional reform in cultural production.

You offer in your conclusion to Immediacy a few examples of cultural production that facilitate a slower, more intentional consumption of media. One of them is Colson Whitehead’s work, specifically his historical novels. I’m curious what you make of other works within the genre like Bridgerton, which purposefully diverges from accurate historical representation for greater entertainment value. What do you see as the future of genre in general?

Whitehead actually works in a whole bunch of a different genres. There are a few historical novels that maybe constitute a generic center of his experiment, but one of the things that’s so interesting about him as a writer is a willingness to try on genres.

Genres have scaffolding power. To work in a known genre rather than the multi-genre, or the anti-genre, or the hyper hybrid genre is an anti-immediacy strategy because it evokes questions of tradition and innovation. I say in the conclusion that I’m interested in what Raymond Williams calls residual forms as one way of understanding cultural making. There is always new stuff emerging, but there’s also the old stuff that can be reworked too.

This push-pull between making something that’s new from the old, the re-use of forms, that you see as different from hybrid genres — can you talk a little bit more about how you see the ultra-hybrid genre working?

So, I write about some of this in the streaming chapter, but I think that there’s pressure now on genre and the idea that something shouldn't be romance or fantasy; it has to be romantasy — the same with something like dramedy. These are understood as innovative, radical, genius, but as techniques they’re indications of a collapse of structured representation that I think is really problematic. They are de-mediations; they are disintegrations.

And they are often bearing an ideological proposition: that form is containment, that genre boundaries are oppressive. It's this idea that charismatic, artistic intensity emanates from within, in counter distinction to, or in sabotage of existing forms. It’s a totalizing ideology for which immediacy is one name.

Since we’re dipping into culture studies a little bit, I’m curious if you think cultural studies will become increasingly necessary in literary studies now as a method.

I’ve been thinking about this problem a lot with regard to languages and the institutional situation. A number of the traditional humanistic departments that are rooted in language study are being attacked and dismantled by all kinds of forces.

People think that between Google Translate and an increasingly polyglot population that you don’t need those departments. And, I think that the study of culture is one robust way to articulate what we do need, that foreign languages aren't reducible to language. Having a really robust comparative study of culture is one way to reorient what we do in the aesthetic humanities.

Cultural studies as a project and all of its key texts are nearing their 50th anniversary right now. Why did so much of it become immediacy-oriented in the sense of going towards consumer behavior and not towards represented culture or mediated culture, towards aesthetic production? We need to revisit a bunch of those methodological questions.

Do you see your own upcoming work as intervening in some way with this discourse on cultural studies? You talk about “good enough” art, mid art — are you dipping your toes into those waters?

Oh, sure. At the origin of academic work on the middlebrow, a bargain was made to shunt aesthetic form and aesthetic experience and pursue a conversation about the function and the accumulation of cultural capital, and about the functions of social communication.

I think that question has to be reopened, especially because our economic conditions have changed so much and our social relations have changed so much. And what counts as middle culture and middle class life has changed too. So, I’m trying to say that we may have to ask these questions again, differently. We have to invent them anew as a method for the 21st century.

To touch upon perhaps a more prestige form of entertainment, I’d like to ask you about the HBO TV show Succession, which you praise in Immediacy for asking us to engage with it in a way that isn’t about identification. What do you think is particularly valuable about grappling with characters in a way that isn’t about liking them?

Right, when I say Succession isn’t about identification, it’s because the number one thing you will hear, what consumers and critics say about that show is, “I don’t like billionaires; I don’t want to watch that show.”

Identification is hyper dominant as a metric for evaluating and grading or interpreting media and culture, but it’s a very impoverished way to understand what art is in general. But, the show has a lot of ideas that are really fascinating, and it has a lot of interesting forms that are really appealing, disorienting or intriguing. The point is to have those ideas and to encounter those forms.

Novels in particular are machines for putting people in touch with other minds.

Novels in particular are machines for putting people in touch with other minds. It’s a practicing of mediation, putting cognitive processes on the page for the reader to have an encounter with. It’s the one thing that’s really cool about fiction, because it’s very hard — even in your closest friendships or your closest relationship — to know what other people are thinking, right?

Fiction tries to help you know what other people are thinking through very specific formal techniques that have a very specific history. The knowing about how those forms work to engender other kinds of knowledge. Art is providing an intellectual experience, not just an emotional experience. That’s how I see it — that’s how art works.

Anna Kornbluh gave the lecture “Good Enough Art: A Few Theses on Middling Mediations” at WashU as part of the Global Comparative Humanities Working Group’s Comparative Methods Lecture Series.