Rebecca Hanssens-Reed is a writer and translator whose work has appeared in “The Cleveland Review of Books,” “World Literature Today,” “Conjunctions,” “The Best Short Stories 2022: The O. Henry Prize Winners” and elsewhere. Her PhD dissertation examines the connections between deep state politics and the material conditions of literary translation in the postwar U.S. through the life and work of the Missouri-based translator Margaret Sayers Peden.

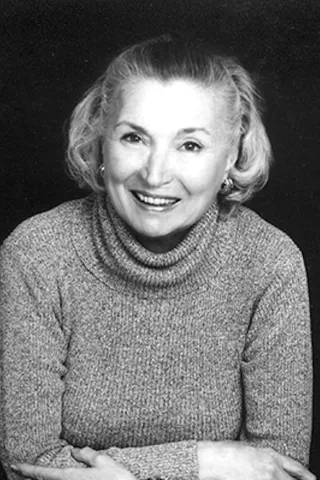

The archive of a translator is a peculiar body of materials. Valued primarily for the insights it provides into the authors represented and the publishers’ involvement in the process, the papers can be surprisingly enigmatic when it comes to understanding the person inhabiting the role of the translator. Margaret “Petch” Sayers Peden (1927–2020), a translator of Spanish who, from her home in Columbia, Mo., dramatically influenced Latin American literature in the United States, sent her correspondence, drafts, galleys, royalty statements and other ephemera to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin starting in the early 1990s. Her collection, which now consists of over a hundred boxes of mostly uncatalogued materials, contains an air of self-effacement. In her letters to the Ransom Center’s acquisitions librarian, Cathy Henderson, Peden repeatedly offered permission for Henderson to discard anything considered unworthy, apologetic about the bulky files (“Maybe I should stick to poetry!”) or remorseful about the scantness of others (“I am sending to the HRC this pitiful little pile of correspondence”). These private notes to the archivist give a sense of Peden’s personality, in particular her humility — a major factor in why her reputation has languished. But what I am more interested in is why certain projects appealed to her and how they may reveal broader attitudes, of hers and those of editors, agents and their ilk, around the ways that the culture industry can respond to, be shaped in or be undermined by geopolitics.

Peden’s skills as a translator developed across the span of many decades and, with that, her approaches to promoting the work of her authors. Her first project, a short novella by Emilio Carballido, was published in 1968 with the University of Texas Press, and her last project, the Novelas ejemplares by Cervantes, was abandoned mid-draft in 2012 due to her failing eyesight. But her politics are harder to parse. A translator’s methodology is their ideology, but so is their alliance to an author’s vision, or to a publisher’s practices with freelance labor. Carballido was a leftist who wrote about alienation in contemporary society, and he also happened to be in the social circle of Communists in Mexico who allegedly partied with Lee Harvey Oswald; another of Peden’s authors on the other hand, Isabel Allende, the niece of the Chilean socialist president who died during a 1973 U.S.-backed coup, once made the proudly conservatist declaration that she “doesn’t consider [her] novels political at all.” But Allende’s publishers at Knopf gave Peden some of the best contractual rights in the industry, including a fair percentage of royalties, and her relationship with their editor, Lee Goerner, was one of the most consistent and respectful of her career.

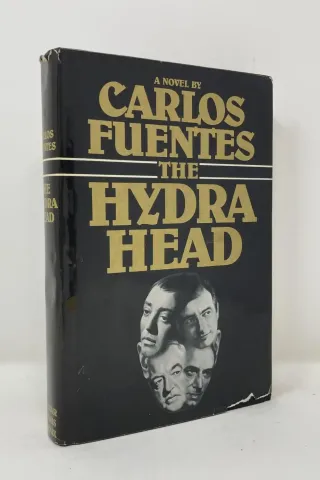

There is a book in Peden’s bibliography that especially piques my curiosity, that she signed on to do around the time she was finally making her name known among major publishers. After having translated Carlos Fuentes’ doorstopper of a novel, the 800-page Terra Nostra — incredibly, the first novel Peden ever did — the next work by Fuentes that she signed on to do was its stylistic opposite, an astringent novel titled The Hydra Head (1978). Marketed by Farrar, Straus and Giroux (FSG) as “the first Third World spy thriller,” the story features a second-level bureaucrat who gets tangled in a web of conspiracy in which the U.S. and Israel partner to secure control over Mexico’s vast oil reserves. The protagonist, Felix Maldonado, at one point wakes up in the hospital to find his face has been replaced with another face, part of the plot to steal his identity and frame him for the assassination of the pro-land-rights Mexican president.

It’s an absurd, at times silly, book, slick in the way that chauvinistic noirs can be, probably one of Fuentes’ worst in terms of style but best in terms of thematic maneuvers. “What cannot be emphasized too much,” Peden wrote in her reader’s report for the book, “is how topical this novel is. Every time I pick up the paper, every time we listen to the evening news, it’s clear how close to the scene THE HYDRA HEAD is!” It is — if you strip away all of the intrigue and jaunty dialogue, the shrill women and the mustachioed villains — a commentary on the rapacious cycles of imperial violence. Every intelligence organization and the countries whose militaries they train and arm are all part of the same exploitative project of state control, and espionage is merely one tiny cell of a much larger fascistic structure. At the end of the novel, Felix, delirious with disillusioned exhaustion, is told: “You are but one head of the Hydra. Cut off one and a thousand will replace it. . . Whether we know it, whether or not we want it, we cannot help but serve the ends of one of the two heads of that cold monster.”

Upon its release in 1978, the novel, which at its core argues for the humanity of Palestinians, was overwhelmingly panned by critics, and it was also the only book for which Peden received hate mail. Within the folder of materials related to the project, which mostly consists of correspondence with FSG editor Aaron Asher over copyedits, Peden included a typewritten letter, dated 1 August 1980, from a signature I have yet to decipher. Jim? Jill? This question of attribution remains the mystery of Peden’s archive that nags at me the loudest: Who wrote this vitriolic letter, which contains some of the most troubling reactionary takes, two full pages of liberalist gymnastics of illogic? The letter writer says they enjoyed the book but couldn’t stand Fuentes’ “leftist distortions” and felt compelled to “fact-check” them. One such so-called distortion was the novel’s depiction of Palestinians as “sweet, gentle people.” “Fact:” the letter states, “The Palestinians are the outcasts of the Arab World. With all their riches and land, no Arab countries want them.” The letter is written in a familiar tone, suggesting they were at least an acquaintance of Peden — maybe this is what allowed the shamelessness regarding their racist polemic. I couldn’t find any record of Peden responding, but her insertion of the letter into the archive itself feels like an implicit commentary.

Fuentes was one of many authors who had been blacklisted from the U.S. in the 1960s for being too critical of American imperial foreign policy; his invitation to give a lecture at WashU in 1964 was canceled when the U.S. embassy rejected what would be one of his many visa applications. The Hydra Head seems to have elicited the same kind of discomfort as we see today when we identify other, as the novel called it, tiny cells of fascistic structure. Peden, in translating such a work, and in making visible in the archive the traces of fascistic sympathies, allows us to discern at least a hint at her belief in the always politically implicated, never neutral, role of the translator.

Headline image: Political cartoon showing a Standard Oil tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol and one tentacle reaching for the White House. Published in Puck, v. 56, no. 1436 (1904 Sept. 7). Courtesy the Library of Congress.