Interview with film scholar Diane Wei Lewis

In the years after World War I, a new proletarian movement took hold in Japan. A driving force for the new leftist politics was Prokino, a collective of artists, creators and thinkers who saw the potential to document and spread their message via film. Faculty Fellow Diane Wei Lewis, assistant professor in Film and Media Studies, shares a preview of her current book project, a full-length study of Prokino and its place in Japanese interwar history.

How did you become interested in your project, which you’ve tentatively titled “Prokino: The Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1929–1934”?

I became interested in Japan’s proletarian movement while researching the celebrity artist Murayama Tomoyoshi for my first book. Murayama was an avant-garde artist and provocateur who dabbled in many different kinds of media in the 1920s. He was like a prewar Japanese Andy Warhol. In addition to theater, dance, the essay and short story, painting and the plastic arts, Murayama worked in a number of commercial genres, such as illustration, design and film. He had a flamboyant public persona and often incorporated references to commodity culture in his work, contributing to an emerging critical discourse on the rise of consumer culture and popular media in modernizing Japan.

Murayama went on to become one of the leading figures in the proletarian theater movement, as well as an important advocate for the political use of film. That fascinated me. In fact, it wasn’t just Murayama: Many modernist writers, artists and intellectuals became involved in the proletarian movement. I became interested in the relationship between the modernist and realist factions of the proletarian movement and, in particular (since I am a film scholar), the different approaches to cinema within the movement — from teaching farmers and workers how to make movies with amateur film equipment, to using film projection in experimental stage designs, to making agitprop newsreel films.

Set the scene for us: Can you describe the rise and importance of the country’s proletarian movement?

The proletarian movement came out of these developments, emerging in the 1920s and starting off as a fairly broad, coalition-based movement that was comprised mostly of middle-class/elite writers, artists and intellectuals who wanted to create a more progressive, pacifist society. The movement gradually became more focused on political organization (recruiting and politicizing factory workers and tenant farmers). It also became more closely linked to the Japanese Communist Party, which was considered seditious and therefore illegal, and was itself guided by policies set by the Communist International, or Comintern.

Since embarking on this project, I’ve decided to focus more narrowly on the organization of the movement and, in particular, the Proletarian Film League of Japan (Prokino). Prokino’s history is so rich and complex that it deserves its very own book. Prokino was one of the groups under the umbrella organization of the proletarian movement, NAPF (Japan Federation of Proletarian Arts), which later became KOPF (Japan Federation of Proletarian Culture).

Who was involved in Prokino, and how did they communicate their ideas?

There are two main strands of film-related activities that contributed to the establishment of Prokino in 1929. The first is leftist film criticism. Around 1927–28, intellectuals at the journals Eiga kaihō (Film Emancipation) and Eiga kōjō (Film Factory) wrote about popular cinema from a political perspective, celebrating progressive artists such as Chaplin, criticizing the links between commercial cinema and capitalist culture, and drawing attention to the ideological messages found in mainstream film.

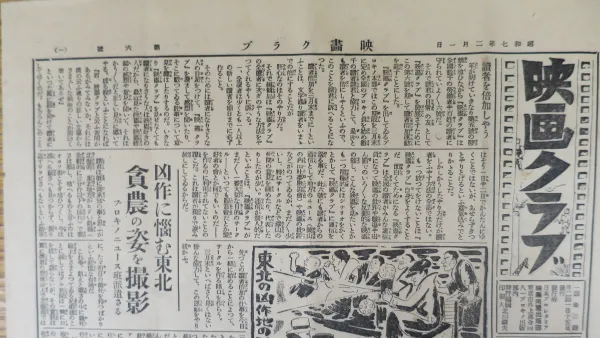

Eiga kurabu [Film Club], February 1932). " class="align-left" src="/files/cenhum/imce/eiga_kurabu_feb_1932_crop_small.jpg" style="width: 300px; height: 223px; margin: 5px 10px; float: left;">The other strand actually comes out of the proletarian theater movement. A member of the Sayoku Gekijō (Leftwing Theater) trunk theater, a mobile theater unit that was dispatched to factories to perform on-site for workers, decided to use an amateur film camera to shoot May Day festivities and labor strikes.

In the first few years of Prokino, there was much criticism of “pencil-pushing” leftist intellectuals who couldn’t imagine any kind of cinema other than studio-based film production and theatrical screenings. The movement was quick to turn away from this kind of film criticism toward grassroots film activities. “Amateur” filmmaking and ad hoc film screenings became central to Prokino’s mission.

For instance, a group of tenant farmers in the village of Shiodome in Saitama Prefecture formed a union to protect themselves from a corrupt landlord. The landlord had been supporting a mistress with funds meant for local elections, selling off the topsoil from his fields to a brick-making company, redrawing the farmers’ plots and penalizing them when they couldn’t produce enough rent from their meager crops. Prokino was invited to film the union’s first cooperative rice planting. They sent two members with a nonprofessional, small-gauge film camera and 200 feet of film. The members learned about the union’s history and wrote up an account of the tenant farmers’ struggles and the filming itself in articles for Prokino’s magazine. I haven’t tracked this film, but the idea is that films such as these would be used to boost union morale.

This particular film, for instance, could be shown in Shiodome and other parts of Saitama, either to farmers in the union (the farmers in the film) or to farmers who had yet to organize. These villages would not have had movie theaters, so Prokino would have brought a screen and a projector and arranged an ad hoc screening.

Only a few Prokino members had experience at commercial film studios. Its most famous members are probably the film critic Iwasaki Akira, the artist Murayama Tomoyoshi and Sasa Genjū, who first shot those 9.5mm films for the trunk theater when he was still a literature student at Tokyo Imperial University.

What will your book add to the history of cinema and proletarian culture in interwar Japan?

There are histories of Prokino in Japanese, including books by Fujita Motohiko and Namiki Shinsaku. Less is available in English, but there are two excellent short pieces on Prokino: a chapter in Markus Nornes’ book Japanese Documentary Film: The Meiji Era through Hiroshima and an essay by Makino Mamoru in the collection In Praise of Film Studies: Essays in Honor of Makino Mamoru, edited by Nornes and Aaron Gerow.

Much of the existing writing on Prokino frames the group’s activities within the history of Japanese cinema and, especially, documentary filmmaking. I’d like to map out Prokino’s activities a bit more broadly, so that a student of art history who is familiar with Murayama Tomoyoshi can understand how film fit into Murayama’s interests, or so that someone interested in labor history can place Prokino’s efforts alongside other programs for workers’ education and recreation. I hope the resulting book will be a social history of Prokino that provides multiple points of entry into their activities, while also painting a general picture of leftwing culture in interwar Japan.