Interview with musicologist Alexander Stefaniak

German pianist and composer Clara Schumann’s dramatic personal life certainly warrants attention. She was reared by an exacting father who orchestrated the details of his child prodigy’s musical development. Despite her father’s disapproval, at age 20 she married Robert Schumann, who had been a student of her father’s and who went on to become one of the most successful composers of the Romantic era. The couple mentored Johannes Brahms, with whom Clara developed a deep friendship. After Robert’s suicide attempt and institutionalization in an asylum, Clara became the sole breadwinner of the family, which had grown to include seven children. It’s enough to fill several books — and it has!

But it would be a mistake to stop her story there, says Alexander Stefaniak, assistant professor of music and Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. From her debut at age nine to her final concert at age 71, Clara Schumann was one of the most acclaimed concert pianists of her time, and her professional career as a performer merits its own in-depth study. Consulting primary sources that he uncovered in German, Austrian, and British archives, Stefaniak is at work on a book that is the first to foreground Schumann’s public activities on the concert stage and to analyze how, as a performer, she strategically engaged with larger musical and cultural currents. Here, Stefaniak gives us a glimpse into his current project, “Hearing Clara Schumann: Performance, Aesthetics and Listening in the Culture of the Musical Canon.”

Who was Clara Schumann? Give us an idea of how popular she was in her own time.

Clara Schumann had one of the longest, most wide-ranging careers of any nineteenth-century European concert pianist. She made her debut in 1828 at the age of nine and continued performing into the early 1890s. Though based in Germany, she toured from Dublin to Budapest, from St. Petersburg to Paris, ultimately giving over 1,200 concerts. In addition to performing, Schumann worked as a composer, editor, and teacher.

As for popularity: The concert world within which Schumann worked was elitist and exclusive, open mainly to the middle and upper classes. Within this world, she commanded extraordinary prestige and celebrity. Her name could sell out a concert, and she became a staple of musical life in several major musical centers: London, Vienna, and Leipzig, for example.

Briefly, how does your book cover Clara Schumann?

Clara Schumann built her career during a pivotal phase in the invention of what we now generally call “classical music” — the decades between the 1820s and the end of the nineteenth century. This musical culture centered on supposed masterworks by venerated composers, a canon that solidified during Schumann’s career. Schumann and her contemporaries embraced the belief that performers should be simultaneously reverent and revelatory interpreters of this music.

My book explores Schumann as a strategist within this culture, showing how she cultivated prestige and asserted authority as an interpreter. Considering this issue means analyzing the ways in which she and other contemporary performers exercised creative and entrepreneurial agency. It also means bringing together a wide variety of sources, including musical compositions, press discourse, and documents of performance events.

Your most recent book was on composer Robert Schumann, the husband of Clara Schumann. How do the projects relate to one another?

This project grew out of my book on Robert Schumann. Researching Robert turned up some really interesting sources related to Clara, and before long I knew that I needed to make her work my next project. And, because my book on Robert explored virtuosity, thinking about this aspect of nineteenth-century music pushed me toward putting performance front and center in this project.

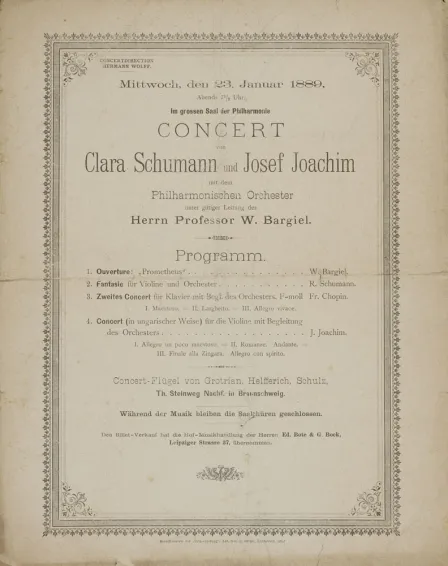

One type of source you’re looking at is Schumann’s concert programs. What kinds of things do those programs reveal?

They contain a wealth of information: when, where, what, and with whom Clara Schumann performed on a particular occasion. One of the archives I visited for this project, the Robert Schumann Haus in Zwickau, has the complete run of her concert programs. That means that we can watch as she selects and discards repertoire over the years or decades, which was an important way in which she shaped her own public image. We can essentially follow her on tour, observing how she adapted to local musical economies and won over local audiences. And, we can watch her build networks of fellow performers and musical entrepreneurs.

What is the most common misconception about Schumann?

I can think of three: First, there’s a long and unfortunate tradition of viewing Clara Schumann primarily in terms of the men in her life — her husband Robert, of course, and their protégé, composer Johannes Brahms. She’s been portrayed as a muse, and as a historical figure who’s interesting mainly because she gives us insight into these men’s music. Many scholars — certainly not just me! — have shown that Schumann was a significant musician in her own right, with her own professional objectives and her own compositional and performance aesthetic.

Second, it’s very common to see Clara Schumann portrayed as a pure idealist: as a performer who selflessly based her career on her deeply held artistic credo and her strong belief in the music she performed. Schumann was undeniably invested in the ideologies of “classical music.” But she was also a savvy strategist and an ambitious professional. My book explores how these aspects of Schumann’s outlook went hand in hand and were crucial to the everyday work of being a concert pianist.

Third, we often assume that classical-music performance means adhering scrupulously to what the composer put in the score. That’s always an overly simplistic view of what classical performance entails, including in the present day. But in Schumann’s time, classical-music performers had many more options for engaging creatively with the music they performed — more ways to put their personal, idiosyncratic stamp on music by other composers. It was accepted (even expected) for performers to improvise introductions to pieces, write their own cadenzas for concertos, take very flexible approaches to tempo and rhythm, and create their own adaptations of other composers’ works. Clara Schumann participated in all of these practices. In many ways, a “classical” performance during her time was much more unpredictable than those of the present day.

In what ways do you see Schumann’s legacy today?

“Classical music” as we know it is a nineteenth-century invention — not just the repertoire, but many of its institutions and core beliefs about performing and listening. Clara Schumann was part of the culture that created this musical world. She harnessed her career to its rise, and in many ways she left her mark on it: for example, Robert Schumann is a central figure within “classical music” in large part because she made his music her calling card.

But at the same time, Clara Schumann and her compositions have figured prominently in efforts to make “classical music” more inclusive — particularly to include more music by women composers on the concert stage and in the classroom. For present-day classical-music audiences, she’s at once the embodiment of an established tradition and an icon of transformation.

Headline photo: “Música” by Hebe Aguilera (CC BY 2.0)