Geoff Ward is associate professor of African and African-American Studies and faculty affiliate in the American Culture Studies program and the Department of Sociology.

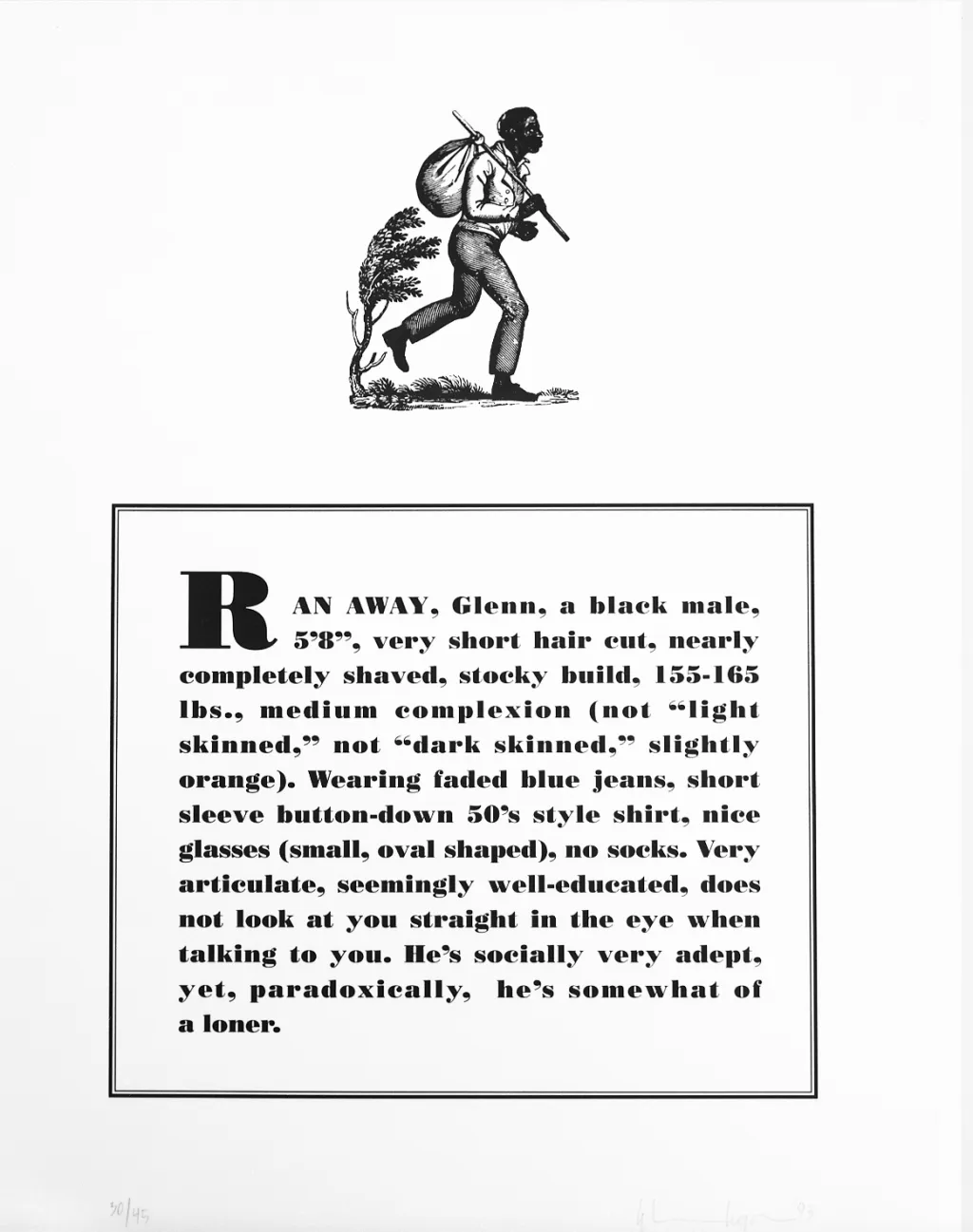

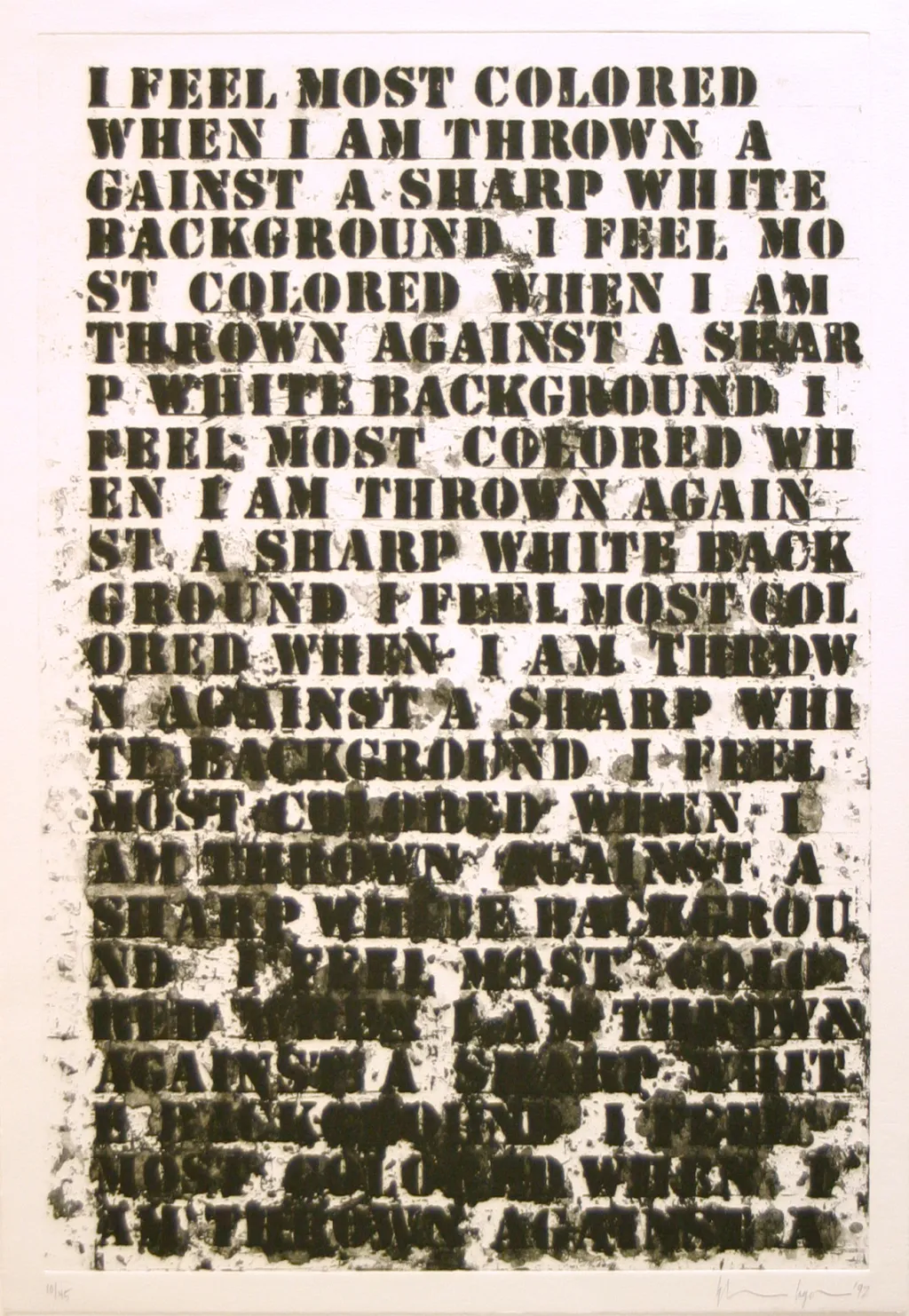

My teaching gallery exhibition Truths & Reckonings: The Art of Transformative Racial Justice reflects over a decade of sociological research on histories of racist violence, their legacies and implications for redress. We know from this research that area histories of enslavement, lynching and other racist repression relate to patterns of violence, conflict and inequality today. Our most recent study shows that county histories of lynching are pretty strong predictors of the odds that children — and especially young black children — will be corporally punished in southern public schools today. Similar studies link other contemporary patterns — like white political conservativism and anti-black sentiment, homicide and incarceration rates, labor market inequality, and heart disease mortality — to area histories of lynching and enslavement. As James Baldwin has stressed, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

Truths and Reckonings is designed as a “pop-up memorial museum,” where groupings of art works from the Kemper Art Museum and archival materials from Olin and other libraries facilitate greater understanding and acknowledgement of this continued presence of past injustice, and hopefully greater commitment to reparative intervention. A companion exhibit at Olin Library’s Special Collections Department showcases artist books commemorating histories and legacies of racial violence, many of them produced by Washington University students, tying the pop-up memorial into more of the campus landscape. Exemplified by museums focusing on the Holocaust, genocide and other atrocities, memorial museums aim to translate education and commemoration around past injustices into greater ethical commitments to present and future justice. Together, the two exhibits demonstrate both the need for this work, and the resources at our disposal to engage in it, if only we are willing.

What has been really exciting to me is that unlike most of the work I do, like publishing and presenting research in academic forums, the exhibits invite more creative expression, are accessible to a broad public and continue for more than two months, enabling engagement with different people from our campus and the wider community, sustained conversations and programming around them. Many WashU students who are unlikely to enroll in my classes can still learn about this work by visiting the teaching gallery, and in several cases I’ve been able to provide tours to groups of WashU personnel (through the Academy for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and the museum’s Lunch and Learn programming), campus residential communities, teachers from area middle and high schools, and people visiting St. Louis.

I came to Washington University in 2018 in part to deepen this work and its potential for impact, confident the university, city and region would offer opportunities to advance this basic research, engage students and translate insights into strategies and practices of redress. This is not only because these histories are so obviously relevant in this city and region (they are relevant across the globe), but because so many St. Louisans are committed to reckoning with these legacies today.

The exhibitions pay close attention to histories and legacies in our region. Many St. Louisans I’ve spoken with about moving here from California to work on these issues respond in the same way. After asking if I’ve lost my mind — who leaves California and comes to Missouri, they exclaim (it turns out there are a lot of us!) — they say, “well, you’ve come to the right place,” then describe St. Louis as an unusually racist city (or county). Yet I was drawn here more so by the broader history of Missouri, freedom’s compromise state, and the Mississippi River valley, a catchment area for so much of our national and global history of racist violence and exclusion. Missouri statehood literally rests on an agreement to violate democratic principles of freedom and equality, in the interests of white racial dominance. The Mississippi River has functioned literally and figuratively as America’s “middle passage,” linking haunting legacies of racist repression in places like southern Illinois, Little Dixie, the Ozarks, the Bootheel, Jefferson City and St. Louis to racial histories of places in the lower river basin, like Memphis; the Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana delta regions; New Orleans and beyond to the global atrocity of the transatlantic slave trade. These legacies have grown concentrated in river cities like St. Louis by patterns of dislocation and dispossession, migration, resettlement and continued exclusion here in our (gated) gateway city.

The teaching gallery program at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, where faculty can guest curate exhibitions related to their scholarship — and the university art and library collections my exhibits draw on — are great examples of the opportunity that attracted me to Washington University. Furthermore, the support I have received from the museum director, curators and other staff, and from Olin librarians, is further evidence that the common, escapist refrain that “we cannot change the past” is giving way to greater acknowledgement that we can and must change its meaning and impact today.