Timothy Moore is the John and Penelope Biggs Distinguished Professor of Classics. Cathy Keane is professor and chair of the Department of Classics.

RELATED EVENT

Virtual Symposium on Plautus and the Women of Washington University

Saturday, February 6, 2021

Morning session

9:00–9:45 am - Timothy Moore (Washington University in St. Louis): “Women and their voices in Plautus’ Rudens”

9:45–10:30 am - Julia Beine (Ruhr-Universität Bochum): “‘Something of great moment is about to happen’: Plautus’ Rudens in translation and performance by the Ladies’ Literary Society of Washington University”

11:00–11:45 am - Judith Hallett (University of Maryland): “Ultra veritatem muliebris vis: women classicists in the dawning of post-bellum America”

11:45 am–12:30 pm - Amanda Clark (Missouri History Museum): “Women’s cultural and intellectual clubs of late 19th-century St. Louis”

Afternoon session

2:00–3:30 pm: Online performance of Plautus’ Rudens by members of the Washington University and local community, using the 1884 translation by the Ladies’ Literary Society of Washington University

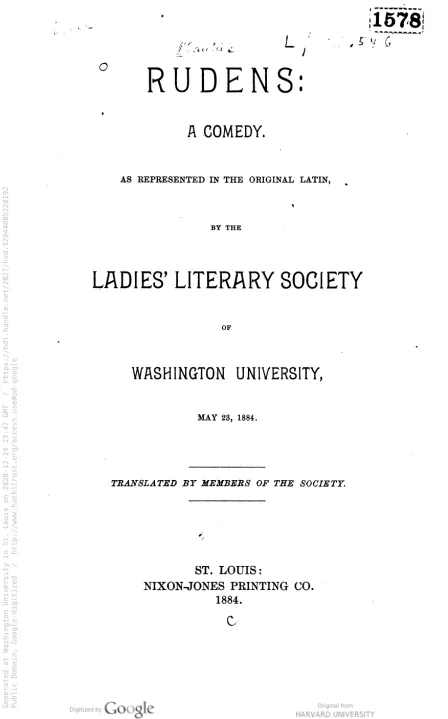

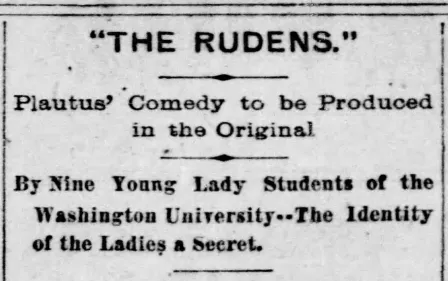

Washington University witnessed a remarkable performance in May 1884. The University’s Ladies’ Literary Society, a group of women undergraduates, performed in Latin the comedy Rudens (The Rope), by the ancient Roman playwright Plautus (c. 260–184 BCE). What would inspire these women to present a 2,000-year-old play in a language virtually no one in St. Louis (or anywhere, for that matter) could speak with any fluency?

The women were no doubt motivated in part by the prestige of Latin — and of ancient Greece and Rome in general — in 19th-century American life. By memorizing and performing effectively large amounts of Latin, the women demonstrated their mastery in a field that was dominated by men. Reviewers of the production were suitably impressed, noting with pride the high cultural level of St. Louis that allowed such an event to occur.

The production was a tour de force; however, it would bring the women more than just the opportunity to show off. They found in Rudens a play that was congenial both for its lively plot and characters and for its unique perspectives on gender.

In Rudens the young woman Palaestra, who was captured and sold into slavery as a child, is reunited with her parents after escaping from a pimp, and she can marry the young man Plesidippus. As so many comic playwrights have followed Plautus in building their plays around this basic plot — the reunification of long-separated loved ones leading to marriage — the plot would feel familiar to its 1884 cast and audience, as it does to us. Carrying out the plot is a boisterous cast of characters unusually large for a Roman comedy, including Palaestra and her friend Ampelisca (also enslaved), the nasty pimp and his equally odious friend, three enslaved men whose comic antics include a tug-of-war that gives the play its name, and a group of dancing fishermen.

Roman comedies like Rudens might seem at first sight to represent only the voices of men. As in most drama of ancient Greece and Rome, male actors — almost all of slave or freedman status — played all the roles in these plays, including the female characters, when they were first performed. The male characters dominate the plays’ discourse. Even the enslaved male characters speak frequently and at length, articulating their yearnings, worries, and schemes — indeed, as the signature-type character of Roman comedy, they contribute significantly to the plot and wit of Rudens. Plautus’ plots center around the successful attempt of a young man to acquire (sometimes for marriage, sometimes just for sex) a woman he loves, and more often than not the desires of the woman are not considered (in Rudens, for example, we never learn what Palaestra thinks about Plesidippus). The plays abound in misogynistic statements from both male and female characters. One character in Rudens even says, “a good woman is always silent rather than speaking.”

Yet, paradoxically, Plautus’ comedies offer both one of our best sources for the lives of women in ancient Greece and Rome and a number of female characters whose influence has been felt throughout modern theater. Plautus’ plays were musical theater, and women characters sang some of the best songs. In both their songs and their speeches these characters demonstrate how women of any status can survive and even thrive in a “man’s world” through mutual cooperation, integrity, cleverness, and good sense.

“It presented to the citizens of St. Louis a spectacle which will long live in the memory of those who were so fortunate as to be present on the occasion. As a leading paper of our city said, ‘The talent is here, the culture is here, and the interest here.’”

— Washington University Student Life, May 1884.

Follow this link to read the entire article.

Rudens offers a remarkable set of women’s voices. Early in the play Palaestra and Ampelisca, shipwrecked, sing a long song lamenting their fate and rejoicing when they find each other. In the process they show how their own cooperation, along with their piety, allows them to survive the vicissitudes imposed upon them by men. Though Palaestra and Ampelisca are enslaved, and therefore at the very bottom of the social hierarchy, they are rescued by a distinguished priestess, as bonds of gender overcome divisions of social class. When Ampelisca is sent by the priestess to fetch water from the house next door, she is sexually harassed by the man who greets her, but she outwits him in ways that would have been as familiar to the members of the Ladies’ Literary Society as they are to women in the #MeToo age. Finally, shortly after a male character makes the claim above about good women’s silence, it becomes clear that without words from a good woman resolution of the plot is impossible. Palaestra’s words — and her excellent memory — save the day, as she reveals without even looking at them a set of tokens that proves who her parents are.

Rudens thus allowed the members of the Ladies’ Literary Society to present a set of women whom they would have found congenial and inspiring. They also performed all the male roles themselves, reversing ancient practice and complicating the play’s gender messages in ways Plautus could not have dreamed of.

Headline image: Photo by Saskia van Manen via Unsplash