Meredith Kelling is a doctoral candidate in English and American Literature and a Harvey Fellow in American Culture Studies. In 2020, she was awarded a Graduate Summer Research Fellowship by the Divided City initiative, during which she conducted research on memoirs and novels that include recipes and culinary imperatives.

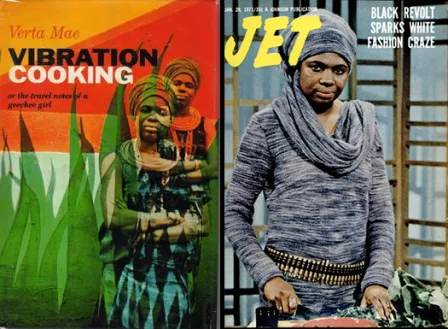

“This book has legs,” my advisor, Rafia Zafar, said to me over Zoom this summer. She held up her first edition copy of Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor’s cult classic, Vibration Cooking, acquired to replace some number of copies that have walked off her shelves into the kitchens and offices of friends. As a cookbook, Vibration Cooking’s mobility makes especial sense. Recipes, after all, are highly circulated texts, printed in newspapers and on food packaging, scribbled down on index cards, and collected in community cookbook projects long popular in church and school fundraising campaigns. Long before Twitter, recipe texts engendered sociality between cooks and their kitchens.

Because the authorship of the recipe and the work of cooking are both coded as especially female in American culture, the route a recipe takes —passing through cooking and writing hands — traces intersections between women’s working and writing cultures. Even though writing and household work have been structured as rivalling tasks in women’s literary history (just think of Virginia Woolf’s bare request for women writers to have rooms of their own) the recipe tells a different story. In a recipe, acts of culinary work and writing motivate each other. The recipe creates discourses around food and cooking, but also around the power structures and material conditions that surround food and meals. Such communication can go undetected by unsympathetic readers because of how domesticity is regarded as politically or intellectually ineffectual. Though recipe writers certainly don’t always seize upon such an opportunity, the combination of the recipe’s circulatory potential and its being overlooked as a textual vestige of “feeble” women’s culture mark the recipe as a text with the potential to foster solidarity between women and even to enact subversion of patriarchal and white supremacist norms.

As I studied Vibration Cooking for a dissertation chapter, I became interested in the way the book’s “legs,” or its circulatory power, served not to solidify some stale idea of women’s work and status in the home and kitchen, but to deliberately upend those notions while critiquing the white supremacy implied in American domesticity. Smart-Grosvenor dedicates the book “to my mama and grandmothers and my sisters in appreciation of the years that they have worked in miss ann’s kitchen and then came home to TCB [take care of business] in spite of slavery and the moynihan report.” Here she names her own network of recipe exchange as specifically Black and female, and documents the labor of Black women in the kitchen who created and sustained their own care networks in spite of the racist cultural norms that compelled them to work in white kitchens. In Vibration Cooking, the recipe’s circulatory power is harnessed to enact Black female solidarity.

Vibration Cooking’s recipes do something, then, beyond issuing rote culinary imperatives such as “first, take one cup of flour.” While her recipes give instructions, they also form liberatory spaces for cooks to improvise on received knowledge, to create and forge connection at once, as Smart-Grosvenor famously remarks at the beginning of her text: “And when I cook, I never measure or weigh anything. I cook by vibration. I can tell by the look and smell of it.” Cooking by vibration is not sloppy cooking, but formal expressive practice drawing on deep cultural knowledge: “If you have any trouble, I suggest you check out your kitchen vibrations. What kind of pots are you using? Throw out all of them except the black ones.” Keeping only the “black ones,” or the cast iron pots that figure centrally in diasporic cooking, is Smart-Grosvenor’s gesture of deference to generations of Black women in the kitchen.

As words go, “vibration” has a very ’60s feel to it. It affords us an opportunity to view Smart-Grosvenor’s kitchen arts as informative to the Black Arts Movement (BAM), which had its own fixation on the utility and circulatory power of art — specifically towards the aim of global Black liberation. “Useful” Black Arts often took shape in ephemeral materials and social events: poetry readings, jazz performances (and combinations of the two), celebrations of African diasporic culture in food and fashion, widespread political activism and dissemination of “mass art.” As its key belletrist Larry Neal announced in an eponymous essay on the movement: “The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community.”

Indeed, Smart-Grosvenor’s book is as dedicated to documenting this social world of Black creative-political expression as it is insistent on Black culinary praxis as a Black Arts expressive form. Her cookbook is filled with names of BAM’s key creatives and intellectuals: the writers Charles Fuller, Larry Neal, Askia M. Touré and Amiri Baraka; the musicians Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Nina Simone and Miriam Makeba; and the visual artists Bob Thompson and Joe Overstreet. Reading Vibration Cooking, then, for its social networks reveals some aspects of how BAM operated. Its innovative interoperation of musicianship, poetry and performance built a network of artistry, amateurism, collaboration and improvisation that it would be very incorrect to label as haphazard, sloppy or incidental.

In view of the cruciality of such social connections, it is only right to read Vibration Cooking as an illustration of the everyday work of generations of Black women that fed — literally and figuratively — Black political consciousness. Vibration Cooking cites origins for Black Power and Black Art in feminized, overlooked labors like cooking and carework. Indeed, Black Power is what’s happening in Vertamae’s kitchen, hidden in the guise of one of the most overlooked of textual genres: the recipe. Reading Smart-Grosvenor’s recipes against the matrix of Black Arts permits an understanding of recipe writing as a creative labor akin to the writing of poetry. The recipes do liberatory things. “I am a Black woman,” Smart-Grosvenor writes, introducing a series of recipes using okra and citing okra’s ubiquity in African diasporic foodways. “I am tired of people calling me out of my name. Okra must be sick of that mess, too.” In insisting on “okra” being called “gombo” throughout her book, Smart-Grosvenor re-orients readers to the Black diaspora, the food and language histories therein, and — most importantly — how centrally Black women’s creative labors have figured into these complex histories in ways that so often escape textual representation. She recasts Black female culinary work — long misrepresented through racist stereotypes such as Mammy and Aunt Jemima — as Black Power praxis.

Because of the recipe’s status as a feminized, somehow unserious text, it might be too easy for readers to interpret Vibration Cooking as “merely” one woman’s account of feeding more famous (and so often male) poets and jazz musicians as they developed their own work. We must remember, as Smart-Grosvenor obviously did, the overlooking of the recipe and the opportunity it presents for mass art, for the circulation of cultural knowledges. Long before he won a Pulitzer for playwriting, Smart-Grosvenor’s childhood friend Charles Fuller wrote, “[the] longevity of [Black writing] will be limited to the nourishment it provides its people, and its writers should be considered no more than good cooks.” It is in this identification of a “good cook” that we might see Fuller’s ideal BAM artist as already at work in the kitchen, already carefully managing families and social networks through a combination of oral, written and culinary expressive practices that remain under-documented in historical representations of the long civil rights movement. Imagining a network of the Black Arts Movement with Vibration Cooking at its center — as, one could say, Smart-Grosvenor is herself doing with these recipes — makes it possible to see how BAM’s expressive powers riff on these informal, surreptitious and under-examined collectives across time: the “good vibrations” between generations of Black women at work in the kitchen.

Headline image: “Okra in a Bowl” by Neha Deshmukh via Unsplash