Interview with Faculty Fellow Abram Van Engen

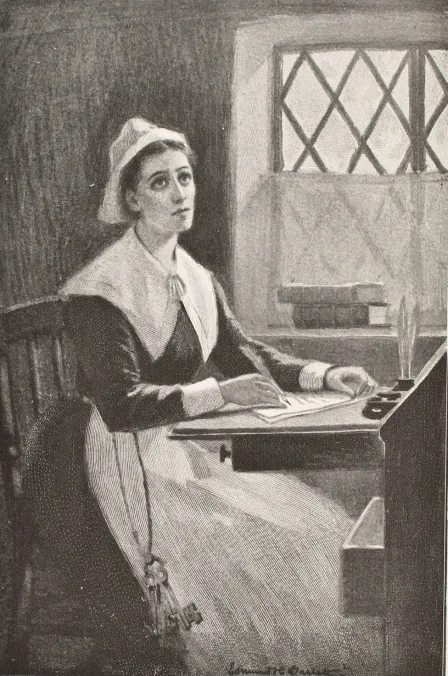

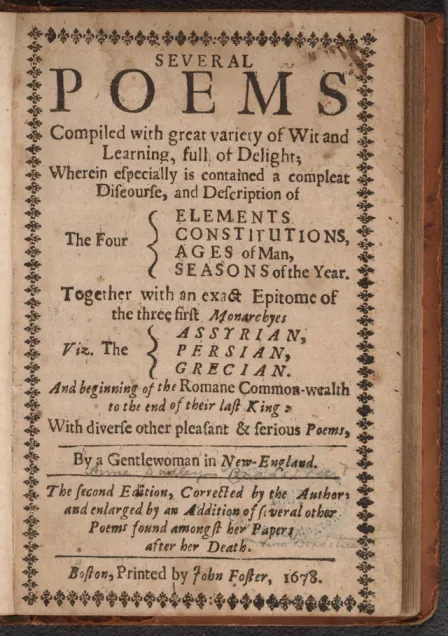

It’s time for a new biography of Anne Bradstreet, says Abram Van Engen, professor of English and a Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. In 1650, Bradstreet became the first person from British North America to publish a book of poetry, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. “[The book] made her famous, and for almost four centuries, Bradstreet has been canonized, printed, anthologized, studied and taught,” Van Engen says. But the most recent biography appeared 30 years ago, and recent revelations in the scholarship on 17th-century religion, gender and politics invite the reconsideration her writing in these contexts. With his book-in-progress, “Anne Bradstreet’s World,” Van Engen intends to produce a new cultural and literary biography of Bradstreet that will reshape our understanding of both her world and her work. Below, he offers a glimpse into his project.

Who was Anne Bradstreet and what can we learn from her?

Anne Bradstreet was born and educated in England, came to New England on the Arbella in 1630, and lived the rest of her life in Ipswich and Andover. In these towns, Bradstreet raised eight children while producing poetry on every conceivable topic — politics, science, medicine, philosophy, religion and more. Today, she is best known for extraordinary elegies, lyrics and meditations that wrestle with faith and doubt while mourning losses and seeking comfort. Those writings still speak to many readers today.

And today, we can understand those writings in whole new ways. Over the last three decades, a host of scholars have revised what we know about early modern women’s writing, transatlantic Puritanism, book history, English politics and New England conditions. Much of what we thought was unique about Bradstreet actually fits a broader pattern of women’s writing spread across the Atlantic. She was not a solitary genius on the American strand; she was instead a brilliant voice in a much larger movement.

Beyond the broad synthesis I hope to achieve, this biography will contribute to the burgeoning scholarly interest in secularization, building on my work more generally in religion and literature. Recently, scholars such as Alec Ryrie have argued convincingly that unbelief arose most pervasively and persuasively from within the practice and experience of religion itself. Anne Bradstreet’s writings lend themselves to a detailed analysis of this claim, since her work registers so much doubt within the context of faith. I want to explore that tension and its consequences.

What has surprised you in your recent research on Bradstreet and/or publishing in the 17th-century American colonies?

This may sound silly, but I have been surprised to discover just how wide and deep the Atlantic still runs. For years now, scholars have been calling for transatlantic studies of early modern culture. We know that New England was deeply connected to England, not to mention the plight, politics and conditions of those in Africa, the Caribbean, the Americas and elsewhere. We know we should not separate people into national buckets that didn’t, in their own day, exist.

Despite such knowledge, Bradstreet never crosses the sea. Those who study early modern women in England seldom, if ever, mention Bradstreet. If they do recognize her, they talk only about her 1650 London book The Tenth Muse, even though Bradstreet’s most beloved and best-known poems never appeared in it. Meanwhile, Americanists love to teach Bradstreet’s most famous poems, which appeared later, but they seldom situate Bradstreet among the many English women who were writing on many of the same topics and in many of the same ways. Anne Bradstreet’s world was far larger than most treatments of Anne Bradstreet have given us to understand.

What ground will you cover in your new biography on Bradstreet?

The biography has four parts. I start with “The Making of Puritanism,” using Bradstreet’s life to introduce the culture of Puritanism more broadly. Part 2, “The Making of an Early Modern Book,” teaches readers how a book was actually made in 1650. I find that students light up when they learn what went into producing an early modern book — how the paper and ink were made, how the type was laid out and the press was operated. They have no idea how much labor it involved. As I tell the story of The Tenth Muse, I can ask why Bradstreet’s poetry was considered worth so much effort. That leads to part 3, “The Making of Puritan Poetry,” which offers new readings and understandings of Bradstreet’s poems. The last part, “The Making of a Puritan Poet,” explains how Bradstreet has been passed to us through different printings, interpretations and applications of her work across four centuries.

Why is this the right time for a biography of Anne Bradstreet?

A new biography of Bradstreet can fit plenty of scholarly needs and priorities. But honestly, this is a project I just want to do, and I don’t know how to calculate the right time for such endeavors. I’m taking up this book because I care about the subject. And others do, too. When I was first thinking about this project, I received an email out of the blue from a former student who had long since graduated. She wrote in part to tell me all these years later just how much she had been moved by Bradstreet’s poems of mourning and grief, which we read shortly after her own friend had died. Bradstreet still reaches people today.

I love Bradstreet. I think introducing Puritanism through her life and work helps us understand her culture much better, and I think a better knowledge of early modern women’s writing helps us understand Bradstreet much better. But at the end of the day, I get to study and read and write about a person whose life and writings I find utterly remarkable. And the joy of my job is that I get to pursue that interest to the end.

Note: On the podcast Poetry for All, Van Engen and co-host Joanne Diaz read and discuss Anne Bradstreet’s poem “In Memory of My Dear Grandchild Elizabeth Bradstreet.” Take a listen to the short episode here.

Headline image by Olena Shmahalo via Unsplash